Course description

Trying to Classify and Control the English Language

We can perhaps date the Enlightenment, that period in British history when ignorance and religious superstition began to be replaced by scientific enquiry and logical reasoning, to the establishment of the Royal Society in London in 1660. Its purpose was to advance understanding of the world around us, whether physical or social, through the pursuit of knowledge. John Locke, the Scottish philosopher, writing in the 1670s and ‘80s, in his most important work, ‘An Essay Concerning Human Understanding’, said that if language could be used more clearly, then all argument and conflict would just fall away.

We can perhaps date the Enlightenment, that period in British history when ignorance and religious superstition began to be replaced by scientific enquiry and logical reasoning, to the establishment of the Royal Society in London in 1660. Its purpose was to advance understanding of the world around us, whether physical or social, through the pursuit of knowledge. John Locke, the Scottish philosopher, writing in the 1670s and ‘80s, in his most important work, ‘An Essay Concerning Human Understanding’, said that if language could be used more clearly, then all argument and conflict would just fall away.

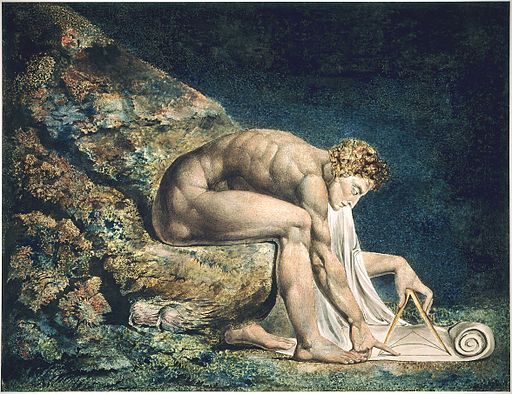

At the time, Latin was the universal language of science and, as it still is today, of medicine, because it was considered that Latin was both understood internationally and so allowed for easy communication between all European thinkers and also was more precise. The Royal Society, in trying to order a chaotic world, included in its efforts the English language, so that this might be used as the language of science. Isaac Newton, also a member of the Royal Society, published his ‘Principia Mathematica’ in 1687 in Latin, but by 1704, penned his Treatise on Optics in English. In this work, Newton invented new words (which he defined so that his meaning was completely clear), re-defined others (like ‘opaque’ which had meant ‘dark’ or ‘stupid’ to mean ‘not allowing the passage of light’) and took advantage of words hardly ever used before, like ‘lens’.

At the time, Latin was the universal language of science and, as it still is today, of medicine, because it was considered that Latin was both understood internationally and so allowed for easy communication between all European thinkers and also was more precise. The Royal Society, in trying to order a chaotic world, included in its efforts the English language, so that this might be used as the language of science. Isaac Newton, also a member of the Royal Society, published his ‘Principia Mathematica’ in 1687 in Latin, but by 1704, penned his Treatise on Optics in English. In this work, Newton invented new words (which he defined so that his meaning was completely clear), re-defined others (like ‘opaque’ which had meant ‘dark’ or ‘stupid’ to mean ‘not allowing the passage of light’) and took advantage of words hardly ever used before, like ‘lens’.

Jonathan Swift, the famous author of ‘Gulliver’s Travels’, wanted the same accuracy in everyday English and was horrified by the imperfect language used in newspapers, which were printed for the first time around the beginning of the 18th century. He noted – with disgust – that Geoffrey Chaucer could no longer be easily understood by readers and that, if this rate of change continued, there would be no point writing anything as the next generation or the one after that would find it incomprehensible. He believed something must be done about this, although if he had looked across the sea to Europe, he could have seen that language councils in France and Italy had not prevented the import of foreign words into everyday speech.

Jonathan Swift, the famous author of ‘Gulliver’s Travels’, wanted the same accuracy in everyday English and was horrified by the imperfect language used in newspapers, which were printed for the first time around the beginning of the 18th century. He noted – with disgust – that Geoffrey Chaucer could no longer be easily understood by readers and that, if this rate of change continued, there would be no point writing anything as the next generation or the one after that would find it incomprehensible. He believed something must be done about this, although if he had looked across the sea to Europe, he could have seen that language councils in France and Italy had not prevented the import of foreign words into everyday speech.

Swift hated the abbreviations used by the upper classes, such as ‘poss’ for ‘possible’ or ‘mob’, a word which we still use today from a much longer Latin one. But he did not like many others either, including short new words, many of which are common in modern speech: ‘bully’ and ‘sham’ among them. He believed that Greek and Latin were more accurate because they no longer changed according to popular taste and should be models for English. Swift wanted to save English by stopping its development.

Samuel Johnson, another eccentric academic figure, also wished to halt changes in the language but, unlike Swift, he had a very practical idea for doing so: writing a dictionary! It was pointed out to Dr. Johnson that a committee of forty of France’s finest minds had taken forty years to put a comprehensive dictionary together, but Johnson thought three years were enough for any Englishman to achieve the goal. He had six assistants – all Scottish – who took notes as he dictated and, seven years later, had completed a dictionary of 43,000 words. There were many deficiencies though in Johnson’s dictionary: it included very few words relating to science, law or medicine; it had no proper nouns; and it omitted words about commonplace things like shoes, clothing, furniture and shipping. He also chose not to include any word he did not understand himself – “How can I?”, he asked innocently – or rude ones. When a lady wondered why, he enquired which one she was looking for. By contrast, he did include archaic words which had been out of use for decades or even centuries. And his explanations of where words originated were sometimes just plain wrong. Others had definitions that were impossible to understand or were comical. For example, he defined ‘oats’ as ‘a cereal fed to horses in England but which feeds the human population in Scotland’.

Samuel Johnson, another eccentric academic figure, also wished to halt changes in the language but, unlike Swift, he had a very practical idea for doing so: writing a dictionary! It was pointed out to Dr. Johnson that a committee of forty of France’s finest minds had taken forty years to put a comprehensive dictionary together, but Johnson thought three years were enough for any Englishman to achieve the goal. He had six assistants – all Scottish – who took notes as he dictated and, seven years later, had completed a dictionary of 43,000 words. There were many deficiencies though in Johnson’s dictionary: it included very few words relating to science, law or medicine; it had no proper nouns; and it omitted words about commonplace things like shoes, clothing, furniture and shipping. He also chose not to include any word he did not understand himself – “How can I?”, he asked innocently – or rude ones. When a lady wondered why, he enquired which one she was looking for. By contrast, he did include archaic words which had been out of use for decades or even centuries. And his explanations of where words originated were sometimes just plain wrong. Others had definitions that were impossible to understand or were comical. For example, he defined ‘oats’ as ‘a cereal fed to horses in England but which feeds the human population in Scotland’.

Yet, despite its many inaccuracies and omissions, Johnson’s Dictionary, published in 1755, was the dictionary for more than a century in Britain and a source of national pride. Strange to say, when he began the work, Johnson had wished to stop changes in the language but, seven years later, realized that language inevitably evolved … although he did not like it.

Yet, despite its many inaccuracies and omissions, Johnson’s Dictionary, published in 1755, was the dictionary for more than a century in Britain and a source of national pride. Strange to say, when he began the work, Johnson had wished to stop changes in the language but, seven years later, realized that language inevitably evolved … although he did not like it.

However, words were not the only area to attract attention. Robert Lowth, Professor of Poetry at Oxford University, published a short grammar of English, which decided the correct arrangement of the language and aimed at the middle classes. Rules that you might know from school and university classrooms may well originate here: never use a superlative when only two things are compared; try not to place prepositions at the ends of sentences; and so on. In other words, if there were two or more ways of expressing something in English, Lowth believed only one could be correct. His short book changed English and the teaching of English forever.

It might interest you to know that Lowth later turned his attention to vocabulary and wished to make using the following words or phrases illegal – yes, that’s right, criminal: bigot, flimsy, nowadays, furthermore, subject matter, banter, fib, drive a bargain…. You get the idea!

Although Johnson’s Dictionary was still respected, in 1857, work began on the Oxford English Dictionary. The aim was simple: to catalogue every word that had ever been written down in English (no matter where in the world), its first appearance in a document (along with the sentence in which it was used), its derivation, including all the changes each word might have undergone since that original use along with authentic examples from each. It was an astonishing aim!

But how was it to be done? The answer was as simple as the aim itself. Volunteers would send to the office words allocated to them with as many examples of different meanings in authentic sentences as they could find. And it worked! At first thousands and then tens of thousands and hundreds of thousands and finally millions of sentences poured in from all over the world. The final dictionary was published in 1933, seventy-six years after it was begun. It had more than 600,000 words, fifteen times Dr Johnson’s dictionary, and ran to twenty heavy volumes.

But how was it to be done? The answer was as simple as the aim itself. Volunteers would send to the office words allocated to them with as many examples of different meanings in authentic sentences as they could find. And it worked! At first thousands and then tens of thousands and hundreds of thousands and finally millions of sentences poured in from all over the world. The final dictionary was published in 1933, seventy-six years after it was begun. It had more than 600,000 words, fifteen times Dr Johnson’s dictionary, and ran to twenty heavy volumes.

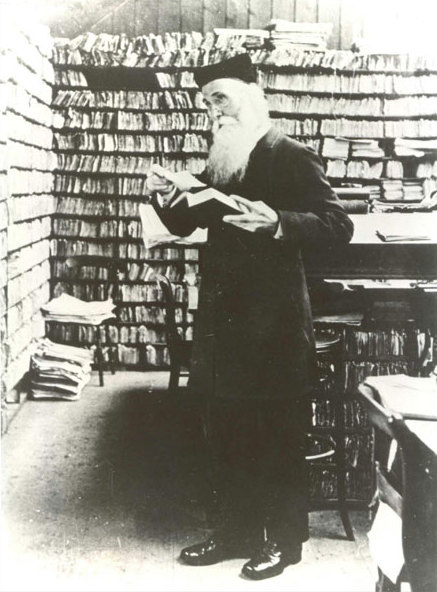

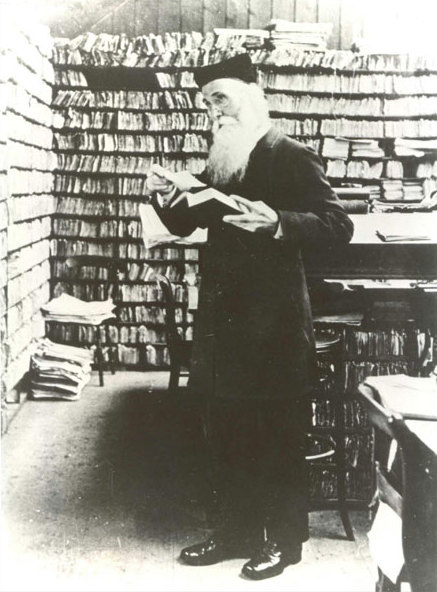

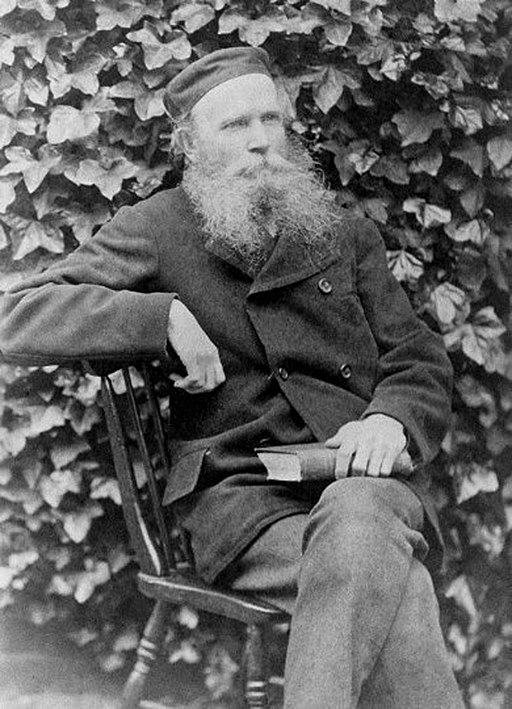

Of course, none of the original team which began the project was still alive, but it is worth mentioning just a couple by name. They are James Murray, the third leader of the project: a Scotsman who had left school at fourteen years of age and who was self-taught. He could speak, read and write the following languages, according to a job application he made: Italian, French, Catalan, Spanish and Latin, and 'to a lesser degree' Portuguese, Vaudois, Provencal & various dialects. In addition, he was 'tolerably familiar' with Dutch, German and Danish. His studies of Anglo-Saxon and Mœso-Gothic had been 'much closer', he knew 'a little of Celtic' and was at the time 'engaged with Slavonic, having obtained a useful knowledge of Russian'. He had 'sufficient knowledge of Hebrew and Syriac to read at sight the Old Testament and Peshito' and to a lesser degree he knew Aramaic, Arabic, Coptic and Phoenician. He did not, however, get the job.

One of the most important contributors to the Dictionary was William Chester Minor, an American, who was held in a hospital for the criminally insane, after having shot a completely innocent man he thought was trying to kidnap him. Minor eventually cut off his own genitals because he believed people were breaking into his prison cell at night and travelling with him to Istanbul to force him to have sex with young children.

One of the most important contributors to the Dictionary was William Chester Minor, an American, who was held in a hospital for the criminally insane, after having shot a completely innocent man he thought was trying to kidnap him. Minor eventually cut off his own genitals because he believed people were breaking into his prison cell at night and travelling with him to Istanbul to force him to have sex with young children.

It is doubtful that the third edition of the Dictionary will be printed but may well appear only online.

The Oxford English Dictionary (or OED as it is widely known) was very different from Johnson’s Dictionary as it was designed to be a record of words, not a guide to which should be used and which discarded.

If you want to watch some videos on this topic, you can click on the links to YouTube videos below.

If you want to answer questions on this article to test how much you understand, you can click on the green box: Finished Reading?

Videos:

1. Johnson’s English Dictionary (2:48)

2. Samuel Johnson: the Dictionary Man (4:34)

3. Who was Samuel Johnson? (2:55)

4. Richard Steadman Jones on Robert Lowth (1:00)

5. Sir James Murray and the Oxford English Dictionary (4:43)

6. The Oxford English Dictionary (7:50)

7. The story of the Oxford English Dictionary (4:38)

We can perhaps date the Enlightenment, that period in British history when

We can perhaps date the Enlightenment, that period in British history when At the time, Latin was the

At the time, Latin was the  Jonathan Swift, the famous author of ‘Gulliver’s Travels’, wanted the same accuracy in everyday English and was horrified by the imperfect language used in newspapers, which were printed for the first time around the beginning of the 18th century. He noted – with disgust – that Geoffrey Chaucer could no longer be easily understood by readers and that, if this rate of change continued, there would be no point writing anything as the next generation or the one after that would find it

Jonathan Swift, the famous author of ‘Gulliver’s Travels’, wanted the same accuracy in everyday English and was horrified by the imperfect language used in newspapers, which were printed for the first time around the beginning of the 18th century. He noted – with disgust – that Geoffrey Chaucer could no longer be easily understood by readers and that, if this rate of change continued, there would be no point writing anything as the next generation or the one after that would find it  Samuel Johnson, another

Samuel Johnson, another  Yet, despite its many inaccuracies and omissions, Johnson’s Dictionary, published in 1755, was the dictionary for more than a century in Britain and a source of national pride. Strange to say, when he began the work, Johnson had wished to stop changes in the language but, seven years later, realized that language

Yet, despite its many inaccuracies and omissions, Johnson’s Dictionary, published in 1755, was the dictionary for more than a century in Britain and a source of national pride. Strange to say, when he began the work, Johnson had wished to stop changes in the language but, seven years later, realized that language  But how was it to be done? The answer was as simple as the aim itself. Volunteers would send to the office words allocated to them with as many examples of different meanings in

But how was it to be done? The answer was as simple as the aim itself. Volunteers would send to the office words allocated to them with as many examples of different meanings in  One of the most important contributors to the Dictionary was William Chester Minor, an American, who was held in a hospital for the criminally

One of the most important contributors to the Dictionary was William Chester Minor, an American, who was held in a hospital for the criminally