Course description

The First War of Independence aka The Indian Mutiny of 1857

In 1757, Robert Clive, won the Battle of Plassey, and brought India under the sway of the East India Company, a de facto arm of the British government. Yet, even as the celebrations were taking place in London, there was a rumour that, in a hundred years, there would be a major and successful revolt against foreign rule. A century later, almost to the day, and the Indian Revolt, the Great Rebellion, the Sepoy Mutiny, the Indian Mutiny or the First War of Independence – it is known by many names, depending on one’s political stance – broke out.

In 1757, Robert Clive, won the Battle of Plassey, and brought India under the sway of the East India Company, a de facto arm of the British government. Yet, even as the celebrations were taking place in London, there was a rumour that, in a hundred years, there would be a major and successful revolt against foreign rule. A century later, almost to the day, and the Indian Revolt, the Great Rebellion, the Sepoy Mutiny, the Indian Mutiny or the First War of Independence – it is known by many names, depending on one’s political stance – broke out.

1857 marked the first time that there had been organized resistance on a wide scale against British rule. But why did it happen in 1857? And why did only the Bengal Army mutiny and not the other two in Bombay and Madras? Why was there so much support among the local population and, perhaps most importantly, why were the revolt and British reprisals later so very bloody?

The first thing to mention, perhaps, is the changing role of the East India Company. Originally, the Company’s role was what its name suggested: it was a commercial enterprise, trading in all the East had to offer, from muslin to tea, spices to opium and many more products besides. Yet, as British influence became more widespread throughout the Indian subcontinent, it steadily withdrew from trade after it lost its monopoly in 1813, and became an agent of the government in London.

The East India Company in its early days, while still a colonial power, employed many scholars and India-enthusiasts who studied the languages of the country, wrote dictionaries, listed and classified its wildlife, and so on. Many married Indian women and took up Indian habits and dress. They did not see it as their business to interfere with Hindu traditions or local government. The East India Company saw its role as establishing fair rule, which guaranteed the safety of the people and their property and maintained an atmosphere allowing trade to flourish.

Yet, as the nineteenth century advanced, there was greater and greater interference from London. Policies on social, religious and military reform were thought up in Britain and it became the role of the East India Company to implement these. A good example might be the laws governing Christian missionaries: in the early years of the nineteenth century, missionaries were simply not allowed to try to convert the people, but, by the 1850s, they were positively encouraged to do so – another dictate from London!

So, first and foremost, the East India Company was no longer popular but seen as interfering.

The second reason for the uprising was the suspicion among the soldiers – both Hindu and Muslim – that the cartridges they had to use contained fat from cows and pigs, and the soldiers had to bite these cartridges to use them in their rifles. This was forbidden by their religions. At first, the soldiers were very reasonable and held discussions with their British officers about their dilemma, explaining that they would be outcasts from their families and communities if it was understood what the soldiers had put in their mouths. Unfortunately, the British response was to imprison – or even hang – them for refusing to obey orders.

Unsurprisingly, the sepoys set their imprisoned friends free.

Colonel Richard Birch was quick to catch on to the importance of the rumour about animal fat being used on cartridges and insisted that the powder should now be contained in paper, not a cartridge, which the sepoys could tear open with their fingers. Sadly, the action came too late.

Another point of difference between the sepoys and the British came over the annexation of Oudh or Awadh in 1856. This was a Muslim princely state, the largest one outside the Mughal Empire and the one from which most sepoys were recruited into the Bengal Army. However, in 1855, the Prince of Awadh decided that he no longer wished to pay tax to the British Empire. This led to the territory being occupied by the British. Many sepoys’ families lost land but their ruler was also deposed. There was much resentment.

Finally, many civilians were angry about British reforms, made with the best intentions, because they seemed to impose English priorities and opinions on the local population. Education is a good example. The British opened an English school for the children of prominent citizens, but there were complaints that the teaching of religion had declined in favour of science and math. And girls were also encouraged to study, something many locals found inappropriate.

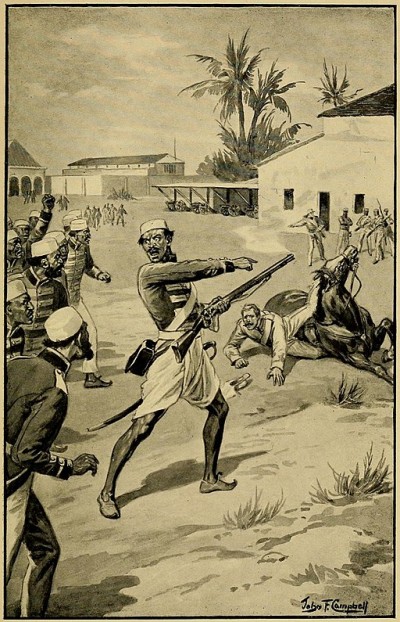

In short, when Mangal Pandey, a twenty-nine year old sepoy from the Bengal Army, said he would refuse to obey his officers and shot at a British officer (but hit his horse), his fellow soldiers refused to arrest him. Mangal then tried to commit suicide but only succeeded in wounding himself. He was court martialed and hanged two days later. The regiment was disbanded dishonourably for refusing to help arrest Pandey. Only the soldier who had restrained him was promoted but, later, murdered by his comrades.

Thinking the punishment very harsh, the soldiers rebelled, killing many officers and marched on Delhi, where they planned to make the eighty-odd year old Emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar, their head. Along the way, many civilians joined them and the revolt spread throughout the countryside. On reaching Delhi, they could not be persuaded by the Emperor to disband and go home. Hundreds of innocent British women and children were massacred by the rebels, even after they had been promised safe passage.

It took the British many months to restore peace throughout India. It was not until July 1858 that a peace treaty was signed, fifteen months after the execution of Mangal Pandey.

British revenge was terrible. Massacres at Delhi and Lucknow, mainly of civilians took place. In Awadh alone, 150,000 Indians died, two thirds of them civilians suspected of supporting the revolt. There had been atrocities on both sides, of course, but the British far exceeded in numbers the murders committed by the rebels. They also used particularly cruel punishments: tying rebels to the mouths of cannon and firing them so that their prisoners were blown to pieces; forcing Muslims to eat pork and Hindus beef before hanging them, and so on.

However, there was at first very little sympathy in Britain for the rebels. Charles Dickens, that great advocate of social reform at home, recommended the genocide of the entire race, for instance. It was only with time, as the scale of the massacres became clear, that the British public became perturbed and, later, disgusted at the number of deaths and the ways in which these murders were committed. Of course, internationally, public opinion had long been on the side of the rebels.

The unfortunate Bahadur Shah Zafar was banished to Burma, where he died in 1862, the last of the Mughal emperors.

However, there was a great deal of soul searching as to why the Indian Revolt had taken place and many changes happend. Some of these might be seen as punitive. For example, the ratio of British to Indian troops was greatly increased and the Indians were no longer allowed to operate artillery. However, there was also to be no more interference in the religious practices of Indians. British officials were told to consult prominent local Indians about new policy and to listen to their advice. The Indian Civil Service was open to Indians for the first time and the paths to promotion were to rest on merit and hard work, not the colour of one’s skin. Queen Victoria herself in 1858 issued a proclamation, saying that Indians were just as important to her as any other of her subjects and they were to be treated with the same respect and fairness.

Of course, the Indian Revolt was tragic for the evil it showed within all of us, the capacity for cruelty and outright prejudice against those of a darker skin colour. Yet, it took another ninety years for India to win its independence.

If you want to watch some videos on this topic, you can click on the links to YouTube videos below.

If you want to answer questions on this article to test how much you understand, you can click on the green box: Finished Reading?

Videos :

1. Sepoy Mutiny - Revolt of 1857 (2:18)

2. Sepoy Mutiny (4:26)

3. The Indian Rebellion of 1857 (5:18)

4. 10th May 1857: The start of the Indian Mutiny (3:00)

In 1757, Robert Clive, won the Battle of Plassey, and brought India

In 1757, Robert Clive, won the Battle of Plassey, and brought India