Course description

The Conquest of Istanbul: the End of the Eastern Roman Empire

On 29th May 1453, the Ottoman Sultan Mehmet rode into Constantinople on his white horse, signalling the end of a thousand years of Byzantine rule of the city and the last day of an empire. Contemporary Greek writers say that the streets ran with blood and, when they heard of the fall of the city, the people of Rome cried openly in public. Everyone would remember exactly what they were doing when they heard the news, much like modern readers can recall where they were when Sheikh Mujib was assassinated or 9/11 took place.

In the end, the defeat of the Byzantines was certain. For centuries, their empire, which had once been the most powerful in Christendom, had been shrinking. The Ottoman Turks had taken land piece by piece from them since the eleventh century and now controlled everything around Constantinople in every direction.

Byzantium’s Christian allies in Italy had not helped their cause either. In 1204, on their way to Jerusalem to rescue it from the Muslims, the Crusaders changed their minds when they saw the wealth of Constantinople and, instead of passing through as allies, robbed and killed the citizens and burnt the city.

In the fourteenth century, plague arrived there before it hit Europe and civil wars reduced the population even further. It was, in fact, because of these civil wars that the Ottomans managed to occupy the land west of Constantinople: one of the warring groups had invited them in and hoped for their support. The Ottomans made Edirne their capital. In effect, the Byzantine Emperor was only the ruler of Constantinople because the Ottomans allowed him to be.

However, the city had a fine and long record of looking after itself. Many foreign powers had tried to conquer it over the centuries. In 626, the Arabs had attacked but could not take it. Two hundred years later, the Volga Vikings were disappointed too. In the tenth century, the Russians had to return to their own land without the prize they so much wanted. Only thirty odd years before, the Ottoman Sultan Murat the Second had failed to enter Constantinople. He had been so confident of victory that he had invited soldiers from all over his empire to join him and share the riches that the city would bring them. In the end, they had to leave empty-handed.

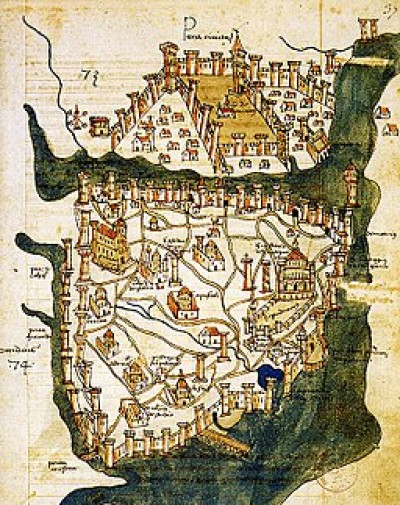

So, why was it so difficult to capture this wonderful city? In the first place, the fifth century walls were very thick and strong. There was an inner and an outer wall and, between them, a moat. What’s more, to enter the heart of Constantinople an army had to cross the River Bosphorus, but the Byzantines put heavy chains across it so that ships could not get near the city.

But the Byzantines themselves had a more important reason. They believed that, in 626, when the army of the Prophet Mohammad had attacked, the Virgin Mary, mother of Jesus Christ, had answered the Byzantines’ prayers and defended the city with them. Some soldiers had actually seen her fighting on the city walls … or so people believed. She had promised always to come to their rescue when she was needed. Finally, they were led by a brave emperor, called Constantine, who had been at the attack of 1422, knew the risks and was ready to give his life to defend Constantinople.

If it is easy to understand how hard it was to conquer Constantinople, it is just as simple to recognise why the Turks wanted it. Three of the five holy cities of Christianity were under Muslim control by the fifteenth century: Antioch, Jerusalem and Alexandria. Only Rome and Constantinople remained in Christian hands. And Constantinople was surrounded by the Ottoman Empire – the Christian jewel in the Muslim crown.

Another reason was that the Prophet Mohammad’s most trusted soldier had died in the 622 attack on the city and Muslims believed the city would, one day, be theirs. There were prophecies about this. And there were more earthly causes too: Byzantium had little military but a lot of diplomatic importance. Byzantine emperors could – and often did – make trouble for the Ottomans with their neighbours.

For instance, Ottoman princes and politicians who became unpopular with their sultan would often escape to Constantinople, where they were welcomed. If the Byzantines wanted to cause the sultan difficulty, they would let these men leave the city, sometimes with soldiers and money.

Then again, Sultan Mehmet was an intensely ambitious man who never stopped until he got what he wanted. He was hated by his people because of his constant demands for more men to fight his wars and more money to supply them. And he wanted Constantinople more than anything else in the world.

But, finally and most importantly, the city was very rich. It was a far greater prize than Edirne or any other city the Ottomans held and would make a fine capital for their ever-growing empire.

In 1453, Mehmet called his army together. This was easily done. He paid men a wage to be ready to fight for him, whether they were needed or not, and few would give that up. They arrived in their tens of thousands – perhaps 60,000 in total – to join him. He also had one hundred and forty ships and cannon to break down the city walls. The largest cannon took more than two thousand men and hundreds of oxen to move.

Inside the city walls, Constantine and his people were quietly hopeful. They had an army of only 4,733 Greeks and another 3,000 foreigners but it was nearly impossible for an enemy to get through the city walls or for the Ottoman ships to reach the city. Besides, the Virgin Mary would protect them. Every man, woman and child helped in the defence of the city. The old and young carried stones to the walls for their soldiers to drop on the Ottomans if they got too close and Christians arrived from other towns and cities to die for the holy city if they had to.

The siege of Constantinople lasted fifty-three days. The huge cannon – so large that they could only fire it a few times each day – had made holes in the city walls, but as fast as they made them, the Byzantines repaired the gaps. The Ottoman soldiers were getting impatient: they wanted the rich prizes of gold, silver, gems and silk that the city contained. Others saw it as a holy war. Finally, Mehmet ordered all his men to fast for three days so that they would please Allah before attacking. He could not sail his ships near the centre because of the chains across the river. Instead, he had them carried to the water.

The night before the attack, the Muslims built huge fires and began to move towards the city. Constantine moved his much smaller army between the inner and outer walls of his city and locked the city gates so that his soldiers would either win and see their families again or die away from them. The noise must have been intense. The Byzantines played organ music and beat drums to make as much noise as possible to frighten their enemies. The sound of the huge Ottoman cannon would have struck fear into the hearts of everyone who heard it, that terrifying noise that signalled death each time it roared.

For five hours, the armies fought and there was no clear result. But when the end arrived, it came very quickly. Many men were wounded and Constantine did not want to open the city gates to let them back in for treatment. Eventually, though, he was persuaded. In the confusion, the Muslims rushed forward and forced their way between his army and the gate. What followed was a massacre.

Constantine’s body was never found. He died leading his men. He had not negotiated for his life or freedom. Mehmet rode into the city and watched as his men attacked the inhabitants and stole everything they could lay hands on. They had three days to get all they wanted, before the looting stopped.

All this might sound very cruel and even barbaric, but these were the rules of warfare at the time. If a city surrendered, it would not be looted. However, if it resisted, the winning army would steal and kill. When the Crusaders took Jerusalem from the Muslims, the murder and theft went on for days and days and the city was almost destroyed. This was not Mehmet’s aim. He did not want the city’s infrastructure damaged, as he intended to use Constantinople as his capital.

As soon as the valuables were taken, he stopped his army from killing. Churches were, in general, protected (although the most famous, St. Sophia, was turned into a mosque). Christians were taxed a little more heavily than Muslims but they were not forced to convert to Islam.

Mehmet brought craftsmen back into the city to renovate where damage had been done. And soon, Istanbul was once again a rich and spectacular capital with an astonishing variety of different peoples and faiths.

The Ottomans kept Istanbul as their capital until the fall of the Empire some 470 years later, when the last sultan, Mehmet VI, was forced to abdicate in 1922. The Ottoman Empire had become “the sick man of Europe” as a Russian tsar called it as long as a century beforehand but was supported by the French and British, who feared a power vacuum that Russia might easily fill.

Although Istanbul is no longer the capital of modern Turkey – Ankara is – it remains the most admired city in the country. It had been beautified by the great lawmaker, soldier and supporter of the arts, Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, in the sixteenth century, with the help of Architect Sinan, the greatest of all Ottoman designers and builders. It had withstood attack by Russian forces in the nineteenth-century Crimean War. It had handed over part of its sovereignty to European powers soon afterwards. But even this indignity only improved the city, as the Europeans added their own distinctive architectural styles to add to the majesty of this splendid city that Emperor Constantine had died defending in 1453.

If you want to watch some videos on this topic, you can click on the links to YouTube videos below.

If you want to answer questions on this article to test how much you understand, you can click on the green box: Finished Reading?

Videos :

1. History of Turkey in 10 Minutes (10:41)

2. The Rise and Fall of the Byzantine Empire (5:20)

3. The Fall of Constantinople 1453 (6:02)

4. The Fall of The Ottoman Empire (3:46)