Course description

The Bengal Famine: A Forgotten Tale of British India

During British rule of India, Bengal experienced several of the worst famines in the history of mankind. The first hit Bengal in 1769 after the British took control of India in 1757, following the Battle of Plassey. This lasted from 1769 to 1773. More than 10 million people died.

Before British rule, India had been the richest country in the world with 27% of world GDP during the 17th and the first half of the 18th centuries. Bengal was the country’s richest state at that time. However, this was far from being the only famine to strike India. Several others happened – in the years 1783, 1866, 1873, 1892, 1897 and finally 1943-44. Although monsoonal delays are thought to be partly responsible for some of these famines as crops arrived late, the policies of the British certainly made a bad situation much worse in 1769. During the Mughal era, the peasants had to pay 10-15% of their harvest to their landlords, but when the British took over in 1757, this was suddenly raised to 50% and explains why Bengal had so little food in store to cope with the effects of a delay in the start of the rainy season. After paying the tax, farmers had nothing left for themselves.

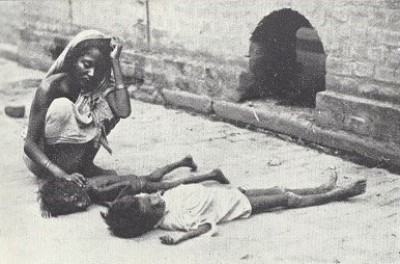

Then, later in 1769, when the rains began, they were so heavy and continued for so many days that the peasants lost most of their crops while they were still in the fields. People began to starve. Hundreds of thousands of them rushed to city areas in search of work and food, but there was simply none available. Most of them died on the streets. Farmlands were left abandoned and there was no food production. The whole of Bengal became a graveyard, and there was chaos everywhere.

Startlingly, no help came from the government; rather the British increased taxation on the crops which were available so that state revenue did not decline. The most shocking fact is that the East India Company made more profit in 1771 at the height of the famine than in 1768 before it had started. The British forced farmers to grow indigo, poppies (for the opium trade) and other similar crops to increase their exports and so their bottom line. They did not focus on vegetables or paddy which could have helped to counter the worst effects of the famine.

Yet, the British did not learn their lesson from this dreadful disaster. Many other periods of famine hit India at fairly regular intervals. Without doubt, however, the worst was the Bengal famine of 1943. Almost three million people died.

Winston Churchill, considered a hero of the Second World War by the Allies in Europe for his resistance to Hitler, was at least partly responsible for engineering this famine. He intentionally diverted food and medical supplies from the starving people of Bengal to soldiers fighting in Europe who, actually, already had enough resources. Comments like the following about Indians suggest that he was very well aware of the consequences of his actions: “Famine or no famine, Indians will breed like rabbits.” Just to make sure that his meaning was completely clear, he added, “I hate the Indians. They are a beastly people with a beastly religion.” (He was referring to Hinduism, not Islam, by the way!) When a correspondent, intending to highlight the effects of famine in Bengal, sent him a letter with a painting of starving people, his only response was, “Then why hasn’t Gandhi died yet?"

Of course, not all the famines to hit India were man-made. Serious drought, caused by low rainfall, or extreme flooding, caused by too much of it, were often responsible for food shortages, but the difference with the Bengal famine of 1943 was that the British government’s reaction actually made it worse than it need have been. Drought was a serious problem in Bengal in the 1940s, but not at the time when the famine began. During 1943, the food supply in Bengal was reduced partly due to the invasion by and surrender of Burma (present-day Myanmar) to the Japanese Army during the war. Burma was one of the most important sources of rice imports for Bengal.

Of course, there were other causes that preceded the famine itself. The population of Bengal had increased dramatically to 60 million in very few years but the supply of food had not kept pace. As such, many landless peasants were already “semi-starved”. Then, the custom of paying the peasants for their work in food had been changed so that they earnt cash. When the food supply was badly affected by late rains, prices rocketed but wages remained the same, meaning that peasants and their families were able to buy less to eat. Then, food was deliberately stored for people in high-paid posts which were considered essential for the war effort: soldiers, civil servants and so on.

But it is claimed that there would still have been enough left over for the people of Bengal to survive, if Churchill’s polices had not meant that the price of food increased insanely. Churchill’s wartime cabinet was warned about a possible famine if they carried on using the food supply of India for their soldiers fighting in Europe. Yet, foodstuffs continued to be exported to Europe even though the Viceroy of India, the most senior British Government representative in the colony, had already requested a million pounds sterling worth of wheat to mitigate the disaster, but no help came from Churchill’s wartime cabinet in London.

To make matters worse, in the coastal areas of Bengal, the boats were also taken away by the British who feared that some inhabitants might help the Japanese in an invasion of India or that their boats could be used by the enemy. (We must remember that Subash Chandra Bose, a Bengali freedom fighter, was in Tokyo and actively helping Britain’s enemy, in the hope that a Japanese victory would mean the end of the Raj in India.) This was another of the causes of the famine. Boats could not be used to import food from other countries, such as Thailand or Malaysia, or for fishing. People began to die as the price of food rose in response to the shortages. Hundreds of thousands of them again migrated to Kolkata in the hope that they might find work and food, but most of them died in open fields or on the roads. The newspapers started to publish news with graphic photographs of the starving and the dead in the streets of Kolkata. Yet, by the time the images were seen around the world, it was too late for three million people!

If you want to watch some videos on this topic, you can click on the links to YouTube videos below.

If you want to answer questions on this article to test how much you understand, you can click on the green box: Finished Reading?

Videos :

1. Bengal Famine 1770 (7:49)

2. Bengal famine (5:27)

3. Churchill and the Bengal Famine (2:29)

4. “Churchill is no better than Hitler” – Dr Shashi Tharoor (6:24)

5. Bengal Famine 1770 (1:50)

6. Did Winston Churchill Kill 4 Million Indians? (8:07)

7. Science Backs Churchill Hand In Bengal Famine Deaths (2:34)