Course description

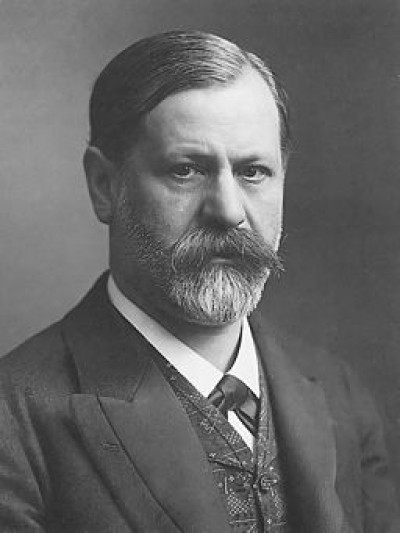

Sigmund Freud and Psychoanalysis

In 1902, the neuroscientist, Dr. Sigmund Freud, began inviting a group of interested health care professionals and academics to visit his home in Vienna, capital of Austria, every Wednesday afternoon to talk about treating troubled patients with a new therapy: talking. There were black coffee, cake and a great deal of tobacco to make their discussions move along more smoothly.

This was the start of the worldwide psychoanalytic movement. And, although some of its ideas may now seem outdated – even ridiculous – Sigmund Freud’s creation has greatly enriched art, literature, and medicine, but, more than that, it has forever changed the way we think about ourselves.

Here are just a few of the ideas that Freud introduced to us: we have an unconscious mind which uses different tactics to protect us from unpleasant realities; we have dreams that help us to work through important happenings in our lives; the experiences of our childhood shape our adult lives; there are stages of development that characterize different phases of our childhood; we are fundamentally sexual beings but we often repress our sexuality because it is unacceptable to society or even to ourselves; that sexuality starts in childhood, not when we reach adolescence. And the list goes on and on.

Many of Freud’s notions may seem very obvious to us now. After all, each and every one of us accepts that childhood experiences have deep effects on how we grow up and the adults we become. But, before Freud, these ideas were unknown or, at least, unexplored. He taught us to look at ourselves, our families and our friends in ways that were revolutionary and not always popular. One British commentator said that Freud went down deeper into the human mind and came up dirtier than anyone before him. Most people felt that it was unsuitable to explore sexuality, especially women’s or children’s sexuality, because it stripped them of their innocence. But, without any doubt, Freud’s psychoanalysis influenced some of the greatest minds of the twentieth century. Several people have compared his work with that of Karl Marx and Charles Darwin as defining our identity.

So, who was this man and what did he discover about himself and us?

Freud was born into a middle-class Jewish family in Vienna in 1856. He was an outstanding student and, before he was twenty, was fluent in German (his mother tongue), French, Italian, Spanish, English, Hebrew, Latin and Classical Greek. He loved literature and was especially impressed by Shakespeare, whom he could read in the original English!

At first, Freud thought he might enter the legal profession but switched to medicine, although he also attended philosophy lectures at university. Towards the end of his studies, Freud devoted more and more time to neurology but also developed an interest in psychology. In 1882, he opened his own private practice dealing with nervous disorders. And it was in this field that the great psychoanalyst made his most significant contribution to the study of the human mind. But his methods were far from standard and have since been criticized for being unscientific.

An example: Freud used cocaine twice a day as a stimulant directly before spending an hour every morning and evening analyzing his own feelings and their root causes. Of course, in the early twentieth century, the drug was legal and was not linked to drinking alcohol and having a great time at parties, but his continuous use has attracted much attention in our own day. (You might remember that Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes was a cocaine user too! So, Freud was not alone!)

Freud used hypnosis as a means of getting patients to dig deep into their pasts and to speak freely about their memories, especially their relationships with their parents and the development of their sexual feelings – feelings which they often repressed because they were too uncomfortable to be looked at in the cold light of day.

He suggested that neuroses – or nervous disabilities that cause people to re-live again and again issues from their early lives – needed to be brought out into the open in conversation between the therapist and patient. Of course, because the most painful of these were buried deep in our minds, some patients were not even aware of them. Freud used free association –the patient saying anything and everything that came into her mind just as it popped up – to uncover those feelings that prevented her from moving on in her life. He believed that if the patient could express these, then she was on the way to accepting and dealing with them.

From this understanding of repression, Freud developed the concept of the unconscious mind, something he believed artists and writers had long known about but which was new to science. After all, if we bury an experience, a feeling, it cannot just disappear. It has a habit of coming to the surface when we least expect it. One way this happens is through dreams, when our unconscious memories and emotions express themselves, only to be forgotten when we wake up.But because these memories are often so painful or uncomfortable, Freud believed that they usually surfaced as symbols. In other words, those of us who regularly dream about drowning or snakes may never have been swimming or seen a serpent. But, to Freud, the sea and the reptile represent something else important in our past. You can read much more about Freud’s ideas on this in his major work, ‘The Interpretation of Dreams’.

Later in life, Freud called the unconscious the ‘id’. He argued that it represented the uncontrolled part of our personalities, where we have unfulfilled wishes that we want to act out at once. Yet, the ‘id’ is kept in check by the ‘ego’, or our rational selves, which uses reason to get what we want and prevents the ‘id’ from immediate action. The ‘superego’ guides us in what is moral, right and ethical – in short, it’s our conscience – and it attempts to steer us towards higher goals.

But the theories for which Freud is best-known – in fact, notorious in some quarters – are those dealing with infantile sexuality. The very idea that young children might have sexual feelings – such as jealousy about their mother’s love for their father – has always been difficult for many of us to accept. This is, of course, precisely the reason why we repress such feelings and pretend that they do not exist, so causing us difficulty in later life, as we have not accepted or understood them and are therefore condemned to re-live the anxiety they cause throughout the rest of our lives.

Partly because Freud never conducted large-scale experiments to test his theories but depended on his own observations with his patients to arrive at them, his ideas have always been very controversial. But there are other reasons too: he was, like the rest of us, a man of his time and, of course, influenced by the world around him. As such, his beliefs about women’s sexuality revolve around men. For instance, one of his central notions was that women were jealous of men because they do not have penises. Of course, such views seem ridiculous a century after he wrote them.

For these reasons, psychoanalysis is not much used by public health services. It is also very expensive because a therapist is highly qualified and needs to spend a great deal of face-to-face time with her patients. There is no reliable method either of determining whether a ‘cure’ has taken place or not. As such, most medical services prefer to allocate funds to prescription drugs that are easily administered, take little time to decide upon and definitely change a patient’s mood and ability to cope with the challenges that everyday life continually throws at us.

Drugs, of course, may prevent undesirable behavior; they may ease our unhappiness; they can give us the energy to get out of bed in the morning; they can calm us down. But they cannot answer the basic questions about why we feel as we do, where our insecurities, fears and anxieties come from. Freud was the first to explore this hugely important area and, in doing so, he changed the way we see ourselves.

He died at the age of eighty-one in England, where he had escaped when Hitler’s Nazis annexed Austria and burnt his books in public, as examples of a depraved mind. His legacy lives on all around us though, probably more than that of any other twentieth century thinker.

If you want to watch some videos on this topic, you can click on the links to YouTube videos below.

If you want to answer questions on this article to test how much you understand, you can click on the green box: Finished Reading?

Videos :

1. Sigmund Freud - Psychiatrist & Scholar (02:18)

2. Sigmund Freud & his Theories on Sexuality, Repression, and Psychoanalysis (07:30)

3. Psychoanalytic Theory - What Freud thought of Personality (04:53)

4. Id-Ego-Super Ego (05:31)

5. Freudian Anxiety, Fear and Insecurities (10:07)

6. Nazi Book Burning (09:41)

7. Sigmund Freud Real Death Story (02:42)