Course description

“Lies, Damned Lies and Statistics”

Qualitative & Quantitative Research Methodologies

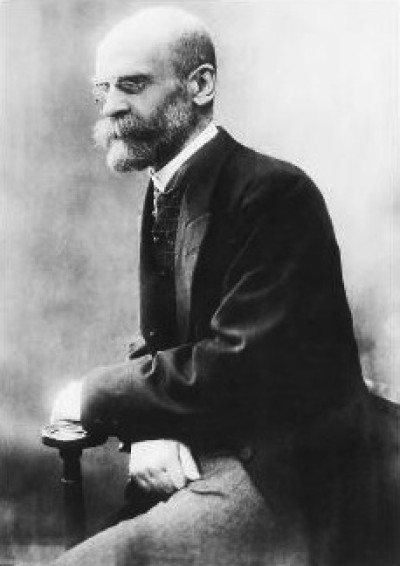

In 1897, the French sociologist, Emile Durkheim, published a case study on research methodology in the social sciences, called ‘Suicide’. In this classic book, he wanted to find an answer to the question of why people commit suicide, using statistical methods in the same way that a physicist or biologist might look at the mass of planets or the structure of plants. In other words, Durkheim believed that suicide notes, diaries, the impressions of the dead person’s family and friends were too personal to provide reliable information on why suicide is more common among some social groups than others. A natural scientific approach which used numbers and statistics would be more objective and provide hard data that social planners might use to decrease the incidence of these terrible tragic events. This approach to looking at society as one could observe an organism is called ‘positivism’.

In 1897, the French sociologist, Emile Durkheim, published a case study on research methodology in the social sciences, called ‘Suicide’. In this classic book, he wanted to find an answer to the question of why people commit suicide, using statistical methods in the same way that a physicist or biologist might look at the mass of planets or the structure of plants. In other words, Durkheim believed that suicide notes, diaries, the impressions of the dead person’s family and friends were too personal to provide reliable information on why suicide is more common among some social groups than others. A natural scientific approach which used numbers and statistics would be more objective and provide hard data that social planners might use to decrease the incidence of these terrible tragic events. This approach to looking at society as one could observe an organism is called ‘positivism’.

Durkheim discovered the following things about suicide:

1. Men commit suicide more often than women (except those who are married but cannot have children);

2. People involved in long-term sexual relationships do not kill themselves as often as single people;

3. People with children are less likely to put an end to themselves than the childless;

4. Protestants take their own lives more often than Catholics;

5. Well-educated people are more likely to end their own lives than those with little schooling;

6. There is more suicide in peace time than during wars;

7. Those living in small communities do away with themselves less often than those in cities.

Durkheim based these findings on official records, especially death certificates, signed by doctors.

From this data, the sociologist was able to identify four basic types of suicide. However, that does not concern us here. More important to us is the trust that Durkheim placed in numbers for deciding the truth about our motivation for putting an end to ourselves.

From this data, the sociologist was able to identify four basic types of suicide. However, that does not concern us here. More important to us is the trust that Durkheim placed in numbers for deciding the truth about our motivation for putting an end to ourselves.

Since his study was published, Durkheim’s dependence on mathematical analysis of data has been often criticized, although his book is still seen today as the first and best sociological analysis of a social issue through scientific measurement. Much of the criticism of Durkheim has aimed at his unquestioning faith in numbers as meaningful, regardless of the situation. Academics have argued that we cannot understand a phenomenon as complicated as suicide just by looking at statistics. We end up with data about it but that does not help us to comprehend the feelings and social or individual pressures that lead to it.

Douglas Adams gave a great example of this in his best-selling 1979 science fiction comic novel, ‘The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy’. The space travelers in the novel have designed a super-computer, called ‘Deep Thought’, with the aim of discovering ‘The Answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe and Everything’. After seven and a half million years, the solution turns out to be 42. Of course, it means nothing to the space travelers.

Douglas Adams gave a great example of this in his best-selling 1979 science fiction comic novel, ‘The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy’. The space travelers in the novel have designed a super-computer, called ‘Deep Thought’, with the aim of discovering ‘The Answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe and Everything’. After seven and a half million years, the solution turns out to be 42. Of course, it means nothing to the space travelers.

Where Deep Thought went wrong was in reducing the most complex question about the meaning of life to a mathematical formula. Of course, in the end, the answer is nonsense because such questions cannot be answered in numbers. His critics would argue that Durkheim tried to do the same and, so, failed to understand the problem facing him.

Another sociologist, Jürgen Habermas, writing in the late 1960s, believed that natural scientific methodologies can never be used to explore social issues because they take no account of history and, so, cannot consider phenomena in context. In other words, if we do not know about events leading up to something, we cannot know what that thing means. For instance, many parents who hit their children today were abused by their own parents in the past; and the same is true of sexual abuse. Without understanding the individual history behind this social problem, therefore, we cannot come up with useful ways to intervene in it.

Sigmund Freud also argued that quantitative methods cannot answer the most important questions about human identity. Positivism, of course, is the belief that collecting data (or information) allows us to use it to take control of ourselves and the world around us. Freud said this was a delusion because none of us is completely aware of what we think and that we often behave in ways that are absolutely unreasonable. (Think of smoking, drinking alcohol, using heroin, having sex without protection or outside marriage, eating unhealthy food and taking no exercise, not going to school or work, and many other behaviors that are, in the end, self-destructive.) Freud argued that our unconscious pushes us towards actions that are illogical but that, often, we are not even aware of these strong underlying forces which decide our motives, feelings and behavior. How can we then understand why a person acts in a certain way by looking at rational indicators expressed in numbers? (At the time Freud was writing, there was no agreement that people even had unconscious thought. He was the first person to suggest it.)

Sigmund Freud also argued that quantitative methods cannot answer the most important questions about human identity. Positivism, of course, is the belief that collecting data (or information) allows us to use it to take control of ourselves and the world around us. Freud said this was a delusion because none of us is completely aware of what we think and that we often behave in ways that are absolutely unreasonable. (Think of smoking, drinking alcohol, using heroin, having sex without protection or outside marriage, eating unhealthy food and taking no exercise, not going to school or work, and many other behaviors that are, in the end, self-destructive.) Freud argued that our unconscious pushes us towards actions that are illogical but that, often, we are not even aware of these strong underlying forces which decide our motives, feelings and behavior. How can we then understand why a person acts in a certain way by looking at rational indicators expressed in numbers? (At the time Freud was writing, there was no agreement that people even had unconscious thought. He was the first person to suggest it.)

Albert Camus (pronounced ‘ka-mu’), a Nobel Prize winning French novelist of the mid-twentieth century, described in his novella, ‘The Outsider’, the murder of an Arab for no clear reason on a beach in Algiers after the death of the anti-hero’s mother. At her bedside, Meursault, the killer, had shown no feeling as he watched her dying – or so the prosecution claimed at his murder trial – and this was evidence that the man was a sociopath with no humane feelings, a man who deserved to be executed for the good of society. But, actually, how could he know any of this? How could the prosecutor understand another person’s motivations, emotions or state of mind? In truth, he could not. If Durkheim had written about murder, instead of suicide, his statistical analysis would not have brought us any closer to understanding Meursault.

Albert Camus (pronounced ‘ka-mu’), a Nobel Prize winning French novelist of the mid-twentieth century, described in his novella, ‘The Outsider’, the murder of an Arab for no clear reason on a beach in Algiers after the death of the anti-hero’s mother. At her bedside, Meursault, the killer, had shown no feeling as he watched her dying – or so the prosecution claimed at his murder trial – and this was evidence that the man was a sociopath with no humane feelings, a man who deserved to be executed for the good of society. But, actually, how could he know any of this? How could the prosecutor understand another person’s motivations, emotions or state of mind? In truth, he could not. If Durkheim had written about murder, instead of suicide, his statistical analysis would not have brought us any closer to understanding Meursault.

Finally, other scholars have criticized Durkheim’s study because he regarded numbers as objective, scientific and, therefore, impersonal. However, these scholars argue that statistics are created by people. This makes Durkheim’s numbers unreliable. Let’s take his finding that people living in cities are more likely to kill themselves than those in villages. First though, according to Habermas, we need to look at the historical context. Most of the population in rural areas of France was Catholic. Crucially, taking one’s own life is a mortal sin – the most serious kind – in Catholicism and, if one dies without receiving forgiveness from a priest for it, one must surely spend eternity in Hell. Of course, the nature of suicide means there is no time to call a priest who, if he were there early enough, would try to stop the person killing himself in the first place or get medical assistance. So, suicide for a Catholic has the most serious consequences, eternal fire. Perhaps this makes it less likely that a Catholic would kill himself.

However, because of the seriousness of the sin and the terrible punishment of eternal damnation, it is also especially painful for the dead man’s family: their husband, son, father or brother is in Hell. Forever. And, then, there is the shame that falls on his surviving relatives. What did they do to force him to this tragic mistake? Why were they unaware that he was considering it? Didn’t they show him enough love? Were they uncaring, cruel, a burden on him?

However, because of the seriousness of the sin and the terrible punishment of eternal damnation, it is also especially painful for the dead man’s family: their husband, son, father or brother is in Hell. Forever. And, then, there is the shame that falls on his surviving relatives. What did they do to force him to this tragic mistake? Why were they unaware that he was considering it? Didn’t they show him enough love? Were they uncaring, cruel, a burden on him?

Finally, Catholicism does not allow suicides to lie in holy ground in a churchyard. (In the middle Ages, suicides were buried at crossroads so that traffic would run over them from four directions, after having their heads cut from their bodies.) The suicide would have no gravestone either, announcing who lay beneath.

Of course, to a city doctor filling out the death certificate, all this means nothing. He does not know if the corpse was a Catholic or Protestant, Jew or Muslim. He does not know the man’s family or feel compassion for them in their grief. He is a stranger. Not so for the village doctor who, of course, knew the man, perhaps was in his parents’ home helping with his birth. He has lived in the same community as the suicide’s family and, naturally, feels deep sympathy with his elderly mother who cries from morning to night and cannot get any sleep. The city doctor might probably record the death as suicide, but the one in the village will make his best effort to write that the death was an accident to spare needless pain to his loved ones.

Now, can we trust the death certificate? What do Durkheim’s numbers mean if we look at them in their social context? They are no longer objective, scientific or neutral because they have been recorded by human beings, who are not always any of these things.

We could discuss many more positivist surveys which have greatly affected the ways we think about ourselves. In the 1940s and ‘50s, for instance, an American professor of biology, called Alfred Kinsey, interviewed more than 5,000 men and 6,000 women about their sexual experiences, classifying them on a scale of 0 to 6, with 0 representing completely heterosexual and 6 completely homosexual. There was a seventh category, X, for people who had had no socio-sexual contact or relationships.

Now, Kinsey’s books, ‘Sexual Behavior in the Human Male’ (1948) and ‘Sexual Behavior in the Human Female’ (1953) caused a sensation and became immediate bestsellers because they discussed areas which nobody had ever talked about before in academic ways. But his findings were also represented as numbers and these ‘gradings’ were decided by the researcher, based on sexual activity. They did not take into account what the interviewee felt about her or his own sexuality. In other words, the survey was all about the physical act, not how people saw themselves as sexual beings. But, surely, how we think of ourselves is the most important part of our sexuality. Consider the young man who plays around with his friends because he is too shy to meet girls or who never gets the chance to because he lives in a very conservative and small community!

Now, Kinsey’s books, ‘Sexual Behavior in the Human Male’ (1948) and ‘Sexual Behavior in the Human Female’ (1953) caused a sensation and became immediate bestsellers because they discussed areas which nobody had ever talked about before in academic ways. But his findings were also represented as numbers and these ‘gradings’ were decided by the researcher, based on sexual activity. They did not take into account what the interviewee felt about her or his own sexuality. In other words, the survey was all about the physical act, not how people saw themselves as sexual beings. But, surely, how we think of ourselves is the most important part of our sexuality. Consider the young man who plays around with his friends because he is too shy to meet girls or who never gets the chance to because he lives in a very conservative and small community!

Another point concerns category X for those with no sexual contact or relationships. Does this really mean these individuals are asexual? What about those who try to keep themselves pure until they are married? Or those with strong religious beliefs?

These days, most large-scale surveys use both quantitative methods and qualitative ones to enrich the statistical data with people’s own stories, insights and opinions. We do this in focus group discussions with the interviewer asking questions and, perhaps, even offering opinions. This may not be objective – some people speak more than others, for instance, or may lie – but at least the records of these chats provide us with more than just the answer, 42, to the age-old ‘Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe and Everything’. Perhaps, we just need to accept that some social issues are too complex to be reduced to numbers.

As Mark Twain, the American author famously said there are three kinds of untruth: “lies, damned lies and statistics”.

If you want to watch some videos on this topic, you can click on the links to YouTube videos below.

If you want to answer questions on this article to test how much you understand, you can click on the green box: Finished Reading?

Videos :

1. Emile Durkheim Suicide study (5:35)

2. Durkheim Biography (07:47)

3. Sigmund Freud and Psychoanalysis (7:39)

4. Hank Hanegraaff discusses ‘Sexual Behavior in the Human Male’(1948) by Alfred Kinsey (3:32)

In 1897, the French

In 1897, the French  From this

From this  Douglas Adams gave a great example of this in his best-selling 1979 science fiction comic novel, ‘The

Douglas Adams gave a great example of this in his best-selling 1979 science fiction comic novel, ‘The  Sigmund Freud also argued that

Sigmund Freud also argued that  Albert Camus (pronounced ‘ka-mu’), a Nobel Prize winning French novelist of the mid-twentieth century, described in his novella, ‘The Outsider’, the murder of an Arab for no clear reason on a beach in Algiers after the death of the anti-hero’s mother. At her bedside, Meursault, the killer, had shown no feeling as he watched her dying – or so the

Albert Camus (pronounced ‘ka-mu’), a Nobel Prize winning French novelist of the mid-twentieth century, described in his novella, ‘The Outsider’, the murder of an Arab for no clear reason on a beach in Algiers after the death of the anti-hero’s mother. At her bedside, Meursault, the killer, had shown no feeling as he watched her dying – or so the  However, because of the seriousness of the

However, because of the seriousness of the Now, Kinsey’s books, ‘Sexual Behavior in the Human Male’ (1948) and ‘Sexual Behavior in the Human Female’ (1953) caused a

Now, Kinsey’s books, ‘Sexual Behavior in the Human Male’ (1948) and ‘Sexual Behavior in the Human Female’ (1953) caused a