Course description

Language Death

WALES : Phillip Capper from Wellington, New Zealand / CC BY (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)

There are about six or seven thousand languages in the world but estimates suggest that 90% of these will be extinct by 2050. Half of these languages have fewer than 10,000 speakers today. But, on the other hand, some languages that were dying are now growing more popular again. Should our governments try to protect endangered languages or is this a waste of time?

Most cases of language death happen because the younger generations no longer use their parents’ and grandparents’ languages as their own mother tongue. Instead, they use the language of school and of their friends. Sometimes governments encourage this. For example, the English did not allow students to speak Welsh Gaelic at school from 1858 for half a century. The use of Welsh started to decline, but that stopped when the education policy changed. About 20% of the population of Wales now speaks Welsh, although not, perhaps, as a first language.

IRISH POTATO FAMINE

In Ireland, Irish Gaelic began to decline in the nineteenth century, when millions left the country or died because of famine. But bringing the language back to life was important to people who wanted an independent Ireland and, so, this was a political decision too. Irish Gaelic is now compulsory for all school students but remains unpopular – because of the very traditional ways that teachers teach it. A new trend though is for expensive private schools to make Irish Gaelic an essential part of the school curriculum. Perhaps if the rich adopt it, its image will change from a language for farmers to one for the elite.

KILLING OF JEWS

A different case is Hebrew. This is the language that Jews used in the synagogue for their religious ceremonies for centuries. But, in 1948, after the Holocaust, the state of Israel was created. Jews, after centuries of soldiers and neighbours burning their homes, stealing their property and killing them in Europe, hurried to Israel. They came from Russia, Germany, Italy and Scandinavia. Soon, Jews from the US and even Ethiopia followed. And they brought their own languages with them. Hebrew, therefore, was a language they could all share and that had a history they all knew from the synagogue. In short, it unified people from many diverse backgrounds around a common identity.

But it’s worth remembering that Hebrew is the only successful example of a language that existed solely in religious texts that is now spoken by millions of people. Other experiments – such as bringing back to life Sanskrit, the ancient language of Hinduism, in India – have not been so successful. There are now only 14,000 first language speakers of Sanskrit, for instance, after twenty years of government effort to re-introduce it – that’s only one in 100,000 of population. Then, Cornish, a language of the south-west of England, which was no longer spoken at all at the start of the twentieth century, now has 3,500 people speaking it as a first language. There is poetry in Cornish and it is used on TV programmes too. But that is after a century of hard work!

RABINDRANATH TAGORE

But what happens when the last speaker of a language dies? Surely, we lose something from the world. Language and culture are not just linked: they are two sides of the same coin. Think about words in Bangla that simply cannot be translated into English because some of their meaning gets lost. How often do we hear people say that translations of Tagore cannot really communicate the great man’s meaning as well as Bangla does? If the words are no longer there when a language dies, can the experience, the feeling, the phenomenon survive?

On the other hand, many people argue that it is a waste of government money trying to protect languages. Let’s look at French, a major language, as an example. The Académie Française (French Academy) is responsible for keeping French. It fights against international words entering the French language. Sometimes it is successful (‘l’ordinateur’ is an artificial word invented for ‘computer’ and is very widely used) but sometimes it is not (think about ‘le weekend’ and the redundant ‘courriel’, meaning ‘email’).

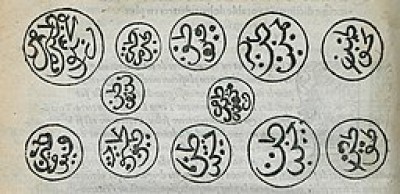

OTTOMAN SCRIPT

The same can be said for Turkish. The founder of the Turkish Republic, Mustafa Kemal Atatűrk, realized that Ottoman, the language of the Empire for centuries, was unsuitable for the Turkish language. For one thing, the alphabet was a complicated mix of Arabic and Farsi, the language of the Persians. It was so hard to learn that children were not literate until they were teenagers. Turkish was changed to the Roman alphabet (with some modifications). But then there was the difficulty of words from Arabic and Farsi, now used in Turkish. Atatűrk set up a committee to make them more ‘Turkish’. Like the French, he had some but limited success: the old Arabic word ‘kitap’ remains, for instance – its ‘Turkish’ equivalent never caught on.

Academics have argued for a language to survive, it must be used in schools; there has to be some financial or professional motivation; and it needs to be available as an electronic language. And, of course, it must be written. But this will never be the case when the last surviving speakers of a language are old and there is no financial reason for youngsters to learn their dying tongue.

Perhaps, it is as natural for languages to die, as it is for customs and beliefs. Nothing lasts forever.

And does this also apply to the many languages used in the Hill Tracts today?

If you want to watch some videos on this topic, you can click on the links to YouTube videos below.

If you want to answer questions on this article to test how much you understand, you can click on the green box: Finished Reading?

Videos :

1. Why Do Languages Die? (3:27)

2. Dead Languages(8:13)

3. Princess Diana Gives Speech In Welsh (Wow!) (2:40)

4. A Brief History of Modern Hebrew (4:51)

5. Origin and History of Sanskrit (14:20)

6. Most Spoken Sweetest Language in the World (1:40)

7. History of the French Language (4:12)

8. The Turkish Language by Kemal Ataturk (10:00)

9. Keeping the Language Alive (4:16)

10. Oxford’s New Global Languages Initiative (3:26)