Course description

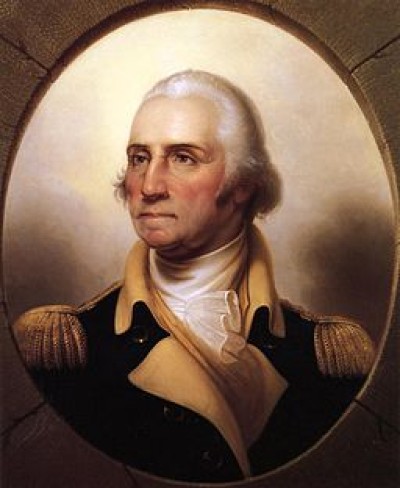

How George Washington Got Involved in the American Revolution

In 1753, at the age of twenty-one, George Washington was sent to negotiate with the French and the American Indians on behalf of the British government. The next year, Washington, in charge of a party of men on their way to build a British fort at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, attacked a group of French soldiers, killing their officer, although the British and French were not at war at the time. This act was widely regarded as an important factor in the outbreak of The Seven Years’ War between American Indians and the French on the one hand, and the British on the other. For the first five years of that war, Washington was an important player on the British side. In fact, he tried hard to become a regular officer in the British Army, although without success. When he resigned, his commanding officer was surprised and disappointed, but praised young Washington as an excellent officer who had the deepest trust in the British.

In 1774, only fifteen years later, George Washington was in charge of the Continental Army that fought against the British in the American Revolution from 1775 to 1783. Of course, he then became the first president of an independent United States and has been seen for more than two centuries as the father of his nation.

In 1774, only fifteen years later, George Washington was in charge of the Continental Army that fought against the British in the American Revolution from 1775 to 1783. Of course, he then became the first president of an independent United States and has been seen for more than two centuries as the father of his nation.

What had happened to turn George Washington, the highly respected ally of the British in their American colonies, into a revolutionary?

Perhaps the first thing to say was that Washington was not, until the start of the Revolution, an American. It’s hard for us to imagine today but there was no American nation or identity until the Revolution helped to create these. Washington regarded himself as a Virginian, a citizen of a state loyal to the British king and his Parliament. It’s true though that his experience of the British had changed since his days as a soldier in the Seven Years’ War. Back in Virginia, he had been a tobacco farmer, supported by English bankers and financiers, people he’d come to see as friends, just as his neighbours did. (When members of his community sent their children to London, it was these same money-men who kept an eye on them and made sure they were managing in the metropolis.) It came as a shock, therefore, when the collapse of the tobacco market in the 1760s meant that there were no more loans available to Washington and his neighbours. Of course, to the bankers, this was just business. To Washington, it meant that his acquaintances across the Atlantic were no longer willing to behave like friends.

To make matters worse, in 1764, a law came into effect (although it was only passed the following year by the British Parliament) that all contracts had to be printed on paper with a government stamp on it. Of course, there was a cost. The reason for the new tax – because that is what it was – was the need to pay for the British Army to be in the American colonies. The Seven Years War had almost doubled the British national debt and keeping an army in North America was likely to cost even more. On the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, on the other hand, the tax was seen as unfair, because citizens of the thirteen colonies, including Virginia, had to pay it (in British pounds, not colonial currency) although they had no voice in the British Parliament. The Americans had grown used to governing themselves and were not happy about being taxed without being represented in Parliament. In short, it was not the tax itself that annoyed the colonists but the principle of being taxed without being asked.

To make matters worse, in 1764, a law came into effect (although it was only passed the following year by the British Parliament) that all contracts had to be printed on paper with a government stamp on it. Of course, there was a cost. The reason for the new tax – because that is what it was – was the need to pay for the British Army to be in the American colonies. The Seven Years War had almost doubled the British national debt and keeping an army in North America was likely to cost even more. On the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, on the other hand, the tax was seen as unfair, because citizens of the thirteen colonies, including Virginia, had to pay it (in British pounds, not colonial currency) although they had no voice in the British Parliament. The Americans had grown used to governing themselves and were not happy about being taxed without being represented in Parliament. In short, it was not the tax itself that annoyed the colonists but the principle of being taxed without being asked.

But things did not get any better. In 1773, the Tea Act came into effect. This was aimed at stopping the import to the American colonies of tea that was not taxed. In December of that year, a group called The Sons of Liberty burnt three shiploads of tea and the British Navy blockaded Boston Harbour until it had been paid for. Things had reached a crisis point.

But things did not get any better. In 1773, the Tea Act came into effect. This was aimed at stopping the import to the American colonies of tea that was not taxed. In December of that year, a group called The Sons of Liberty burnt three shiploads of tea and the British Navy blockaded Boston Harbour until it had been paid for. Things had reached a crisis point.

In 1774, George Washington appeared at a meeting of the Continental Congress in full military uniform. He was elected head of the Continental Army. He began organising the collection of arms. The following year, the British governor seized them and soon fighting began. However, it would be a mistake to think that all the colonists wanted independence. They were probably evenly balanced between those who wanted out of the British Empire, those that remained loyal and about the same number who didn’t much care one way or the other.

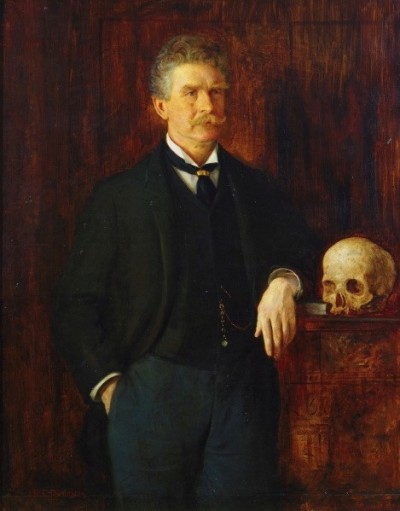

Then, in 1776, Thomas Paine, an Englishman, published a pamphlet called ‘Common Sense’, which argued that the North American colonies should become independent of Britain. It was so influential that the second President of the United States, John Adams, argued that without Paine’s pen, Washington’s sword would have achieved nothing. For the first time, conservative American landowners who had always seen themselves as loyal to Britain began to have doubts. Paine, who by the time he published the work was in America, argued that it was ridiculous for a small island to govern a whole continent. Besides, Britain was not the mother country, as America was full of people from many different European nations. And what kind of mother would treat her child so unfairly? Clearly, Britain ruled the colonies not for their benefit, but for its own and, what’s more, ruled them very badly because the two places were so far apart that efficiency and sympathy were impossible.

Then, in 1776, Thomas Paine, an Englishman, published a pamphlet called ‘Common Sense’, which argued that the North American colonies should become independent of Britain. It was so influential that the second President of the United States, John Adams, argued that without Paine’s pen, Washington’s sword would have achieved nothing. For the first time, conservative American landowners who had always seen themselves as loyal to Britain began to have doubts. Paine, who by the time he published the work was in America, argued that it was ridiculous for a small island to govern a whole continent. Besides, Britain was not the mother country, as America was full of people from many different European nations. And what kind of mother would treat her child so unfairly? Clearly, Britain ruled the colonies not for their benefit, but for its own and, what’s more, ruled them very badly because the two places were so far apart that efficiency and sympathy were impossible.

In 1776, then, the Revolution became the War of Independence, when nothing but a complete separation from Britain was an acceptable outcome of the fighting. It was as a result of that shift in thinking that The Declaration of Independence was written.

George Washington went on to lead the American forces to victory, after a disastrous first year when there were attempts to oust him as commander of the army, and then to become the first President of the United States. He was a man who had a great sense of his own worth and one who was more comfortable with practicalities than with philosophical musings – perhaps the reason why Thomas Jefferson was encouraged to write the Declaration – but also one who had the respect that a new country needed.

If you want to watch some videos on this topic, you can click on the links to YouTube videos below.

If you want to answer questions on this article to test how much you understand, you can click on the green box: Finished Reading?

Videos :

1. George Washington (4:46)

2. The Seven Years’ War (4:40)

3. American Revolution (9:00)

4. Tea Act (3:53)

5. The Sons of Liberty (4:19)

6. Continental Army (1:46)

7. Thomas Paine (3:53)

8. The Declaration of Independence (3:38)

In 1774, only fifteen years later, George Washington was

In 1774, only fifteen years later, George Washington was  To make matters worse, in 1764, a law came into effect (although it was only passed the following year by the British Parliament) that all contracts had to be printed on paper with a government stamp on it. Of course, there was a cost. The reason for the new tax – because that is what it was – was the need to pay for the British Army to be in the American colonies. The Seven Years War had almost doubled the British national debt and keeping an army in North America was likely to cost even more. On the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, on the other hand, the tax was seen as unfair, because citizens of the thirteen colonies, including Virginia, had to pay it (in British pounds, not colonial currency) although they had no voice in the British Parliament. The Americans had grown used to governing themselves and were not happy about being taxed without being

To make matters worse, in 1764, a law came into effect (although it was only passed the following year by the British Parliament) that all contracts had to be printed on paper with a government stamp on it. Of course, there was a cost. The reason for the new tax – because that is what it was – was the need to pay for the British Army to be in the American colonies. The Seven Years War had almost doubled the British national debt and keeping an army in North America was likely to cost even more. On the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, on the other hand, the tax was seen as unfair, because citizens of the thirteen colonies, including Virginia, had to pay it (in British pounds, not colonial currency) although they had no voice in the British Parliament. The Americans had grown used to governing themselves and were not happy about being taxed without being  But things did not get any better. In 1773, the Tea Act

But things did not get any better. In 1773, the Tea Act  Then, in 1776, Thomas Paine, an Englishman, published a

Then, in 1776, Thomas Paine, an Englishman, published a