Course description

English: from the Language of the Devil to the Language of God

It is hard these days to imagine the importance of Christianity in England six hundred years ago – indeed, all over Europe. The Roman Catholic Church was everywhere: in education (which was only concerned with the teaching of Latin,

Greek and religion by priests), in politics (where many government ministers and even rulers of some countries were priests), even in social life. In fact, it was not just advisable for the English to attend church on Sundays, it was mandatory.

It must come as a surprise, therefore, to learn that there was no English-language Bible that people could read to learn more about their religion. That book was only available in Latin and, even then, the priest in church on Sunday read it silently to himself. When he arrived at important parts of the text, a bell was rung so that the people would know those bits were especially holy, but they did not know what they were about. Why, one has to ask, if God was such an essential part of people’s lives, were they not allowed to read the book?

The answer lies in the fact that the authority of the Church required that both a foreign language and a priest had to stand between God’s word, on one hand, and the people on the other. How else could the Church control the people and influence the King and national policy? The arrangement generally worked well for the ruling class as its interests and those of the powerful and incredibly wealthy Church went hand in hand.

Yet, all this was about to change and largely because of one man, John Wycliffe, himself a priest. He believed that every farm boy should have the opportunity to read Christian scriptures for himself. So, in 1380, he began a translation of the

Greek and religion by priests), in politics (where many government ministers and even rulers of some countries were priests), even in social life. In fact, it was not just advisable for the English to attend church on Sundays, it was mandatory.

It must come as a surprise, therefore, to learn that there was no English-language Bible that people could read to learn more about their religion. That book was only available in Latin and, even then, the priest in church on Sunday read it silently to himself. When he arrived at important parts of the text, a bell was rung so that the people would know those bits were especially holy, but they did not know what they were about. Why, one has to ask, if God was such an essential part of people’s lives, were they not allowed to read the book?

The answer lies in the fact that the authority of the Church required that both a foreign language and a priest had to stand between God’s word, on one hand, and the people on the other. How else could the Church control the people and influence the King and national policy? The arrangement generally worked well for the ruling class as its interests and those of the powerful and incredibly wealthy Church went hand in hand.

Yet, all this was about to change and largely because of one man, John Wycliffe, himself a priest. He believed that every farm boy should have the opportunity to read Christian scriptures for himself. So, in 1380, he began a translation of the  Bible from Latin – with many friends and, of course, in secret because what he was doing was illegal. Two years later, the work was complete and then copied out by hand – hundreds and thousands of times – in small editions so that it could be hidden in people’s pockets. Of course, the Church determined in 1382 that the book was the Devil’s work and that anybody reading it should be executed and would certainly go to Hell. The unfortunate John Wycliffe had a stroke and died two years later but a group of men – called Lollards – continued to copy out his Bible and distribute it to as many people as they could, often facing death by fire themselves as a punishment. Wycliffe’s body was dug up in 1428 and burnt, in fact, as a reminder to the people that he was damned for eternity.

But what can we say about the effects that Wycliffe’s Bible had on the development of English? Actually, it seems that the man who went to an early grave for his belief that every Englishman should be able to read God’s word in his own language was actually rather afraid of his task. His Bible introduced more than 1,000 Latin words into English: words like: barbarian, birthday, crime, frying pan, humanity, pollute, madness and communicate, city, justice, profession & suddenly – none of which had ever been used in English before. Worse still, Wycliffe transliterated Latin grammar into English in such phrases as “I am a God jealous and vengeful”, putting adjectives after ‘God’, just as the Romans did. It was as if he were frightened of moving too far away from the Latin, as if he believed God might use that language.

Bible from Latin – with many friends and, of course, in secret because what he was doing was illegal. Two years later, the work was complete and then copied out by hand – hundreds and thousands of times – in small editions so that it could be hidden in people’s pockets. Of course, the Church determined in 1382 that the book was the Devil’s work and that anybody reading it should be executed and would certainly go to Hell. The unfortunate John Wycliffe had a stroke and died two years later but a group of men – called Lollards – continued to copy out his Bible and distribute it to as many people as they could, often facing death by fire themselves as a punishment. Wycliffe’s body was dug up in 1428 and burnt, in fact, as a reminder to the people that he was damned for eternity.

But what can we say about the effects that Wycliffe’s Bible had on the development of English? Actually, it seems that the man who went to an early grave for his belief that every Englishman should be able to read God’s word in his own language was actually rather afraid of his task. His Bible introduced more than 1,000 Latin words into English: words like: barbarian, birthday, crime, frying pan, humanity, pollute, madness and communicate, city, justice, profession & suddenly – none of which had ever been used in English before. Worse still, Wycliffe transliterated Latin grammar into English in such phrases as “I am a God jealous and vengeful”, putting adjectives after ‘God’, just as the Romans did. It was as if he were frightened of moving too far away from the Latin, as if he believed God might use that language. But more general use of English had another powerful supporter in the early 15th century. In 1417, nine years before Wycliffe’s corpse was dug up and burnt, King Henry V, fighting a war in France, sent messages back to London in English, the first time a king had used his own language in writing, although his father, Henry IV – you might remember from our first lecture on English – had started to speak the tongue in his court. That first written message might not seem so important to us but where the king led the way, others followed and, very soon, all official documents and communications were written in English.

Of course, until the early 15th century, there had been no need to make rules about spelling English. As an example, in the north of the country, the word ‘church’ was actually called ‘kirk’ but could be spelled: kirk, kyrke, kyrk, kerk, kirc and kurke.

But more general use of English had another powerful supporter in the early 15th century. In 1417, nine years before Wycliffe’s corpse was dug up and burnt, King Henry V, fighting a war in France, sent messages back to London in English, the first time a king had used his own language in writing, although his father, Henry IV – you might remember from our first lecture on English – had started to speak the tongue in his court. That first written message might not seem so important to us but where the king led the way, others followed and, very soon, all official documents and communications were written in English.

Of course, until the early 15th century, there had been no need to make rules about spelling English. As an example, in the north of the country, the word ‘church’ was actually called ‘kirk’ but could be spelled: kirk, kyrke, kyrk, kerk, kirc and kurke.  The southern version of the noun might be written as: church, churche, cherche, chyrch, chyrche and schyrche. It had not really mattered because nobody wrote the words down in important or official documents. However, all this changed when the written language of government became English. Clearly there was a need for standardization.

But which version of a spelling should be selected as the approved one? There were two ways of thinking in government circles. Traditionalists wanted one of the already existing spellings of a word to be accepted while reformers argued that words should be spelled as they were pronounced. It was the traditionalists who won the argument. And that is why the ‘ough’ combination of letters sounds so very different in these words: though, thought, bough, tough and cough.

Yet, problems for modern students of English trying to master its idiosyncratic spelling do not stop there, because at around the same time an unexplained change happened in the ways we pronounced vowels (‘a’, ‘e’, ‘i’, ‘o’ and ‘u’) in the language and it happened so fast that, by 1500, the language of only 50 years before sounded archaic. But, of course, spelling did not change with pronunciation!

But it was not just the government that decided on approved spelling. When William Caxton brought back Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press from Germany, Chaucer’s ‘Canterbury Tales’ was one of the first works he published and became – at least by the standards of the day – a bestseller.

The southern version of the noun might be written as: church, churche, cherche, chyrch, chyrche and schyrche. It had not really mattered because nobody wrote the words down in important or official documents. However, all this changed when the written language of government became English. Clearly there was a need for standardization.

But which version of a spelling should be selected as the approved one? There were two ways of thinking in government circles. Traditionalists wanted one of the already existing spellings of a word to be accepted while reformers argued that words should be spelled as they were pronounced. It was the traditionalists who won the argument. And that is why the ‘ough’ combination of letters sounds so very different in these words: though, thought, bough, tough and cough.

Yet, problems for modern students of English trying to master its idiosyncratic spelling do not stop there, because at around the same time an unexplained change happened in the ways we pronounced vowels (‘a’, ‘e’, ‘i’, ‘o’ and ‘u’) in the language and it happened so fast that, by 1500, the language of only 50 years before sounded archaic. But, of course, spelling did not change with pronunciation!

But it was not just the government that decided on approved spelling. When William Caxton brought back Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press from Germany, Chaucer’s ‘Canterbury Tales’ was one of the first works he published and became – at least by the standards of the day – a bestseller.  Yet, the printer worried so much about consistency of spelling that he expressed his concerns in writing… and not only about spelling but also grammar. Should he adopt ‘doth’ or ‘does’, for instance? The authors he was publishing often used both interchangeably but, clearly, a single form was preferable.

We can see, therefore, that there were a variety of influences on the development of written English: religious ones because translating the Bible from Latin meant deciding about precise meanings of words and grammatical forms; the legal and socio-political necessity for conformity to standardized grammar and spelling; and, finally, technological developments – the printing press – that required decisions about syntax and lexis.

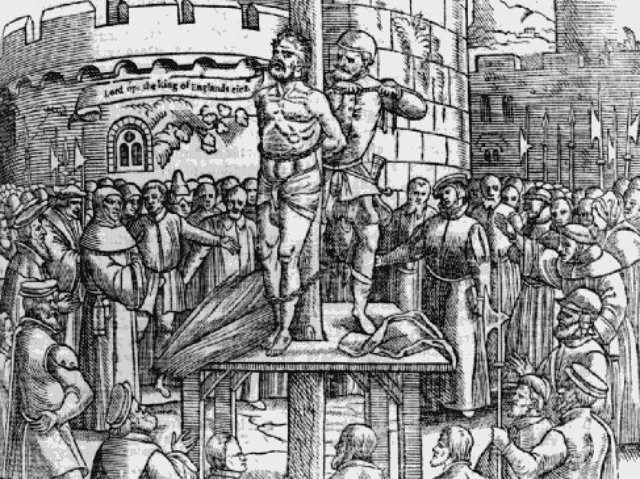

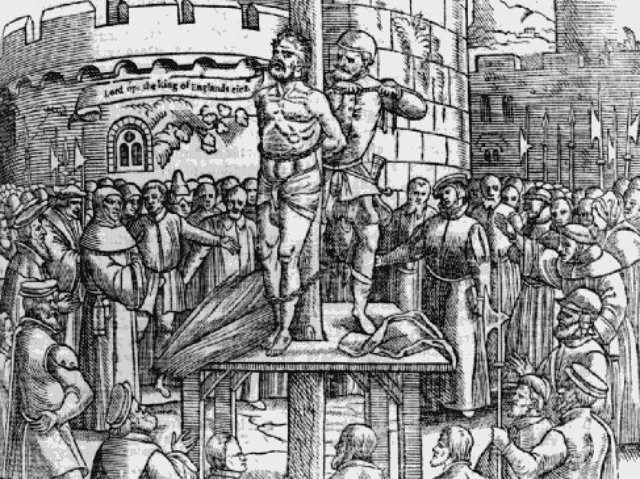

And then, in the sixteenth century, everything was turned upside down once again. This was the age of William Tyndale and William Shakespeare, the two men who did more to shape the quality of English language than any others. First, Tyndale, in 1524, started to translate the Bible – he moved to Germany to be able to do so without fear of imprisonment – but he worked from the original Hebrew and Greek versions (rather than Wycliffe’s Latin one). The beauty of Tyndale’s English, his evident care that each word and phrase expressed not just the meaning of God’s message but also its majesty had a huge impact on the language. But also the fact that now thousands of copies could be produced relatively quickly because they could be printed. Tyndale’s Bible was smuggled into England on ships, which were regularly searched for copies. Thomas More, the author of ‘Utopia’ was horrified and spoke about the shame of ploughboys being able to read the word of God. The head of the Catholic Church in London was so worried about the popularity of the translation that he bought the entire stock from Germany and burnt it. This only meant that Tyndale now had the money to produce more, of course.

Sadly, Tyndale was discovered and kidnapped from the town in Germany where he was living and working, taken to Amsterdam, tried by a Church court for doing the Devil’s work and, of course, found guilty. He was strangled and then his body was publicly burnt in 1536.

However, there were soon more political than religious considerations that decided the fate of Tyndale’s Bible.

Yet, the printer worried so much about consistency of spelling that he expressed his concerns in writing… and not only about spelling but also grammar. Should he adopt ‘doth’ or ‘does’, for instance? The authors he was publishing often used both interchangeably but, clearly, a single form was preferable.

We can see, therefore, that there were a variety of influences on the development of written English: religious ones because translating the Bible from Latin meant deciding about precise meanings of words and grammatical forms; the legal and socio-political necessity for conformity to standardized grammar and spelling; and, finally, technological developments – the printing press – that required decisions about syntax and lexis.

And then, in the sixteenth century, everything was turned upside down once again. This was the age of William Tyndale and William Shakespeare, the two men who did more to shape the quality of English language than any others. First, Tyndale, in 1524, started to translate the Bible – he moved to Germany to be able to do so without fear of imprisonment – but he worked from the original Hebrew and Greek versions (rather than Wycliffe’s Latin one). The beauty of Tyndale’s English, his evident care that each word and phrase expressed not just the meaning of God’s message but also its majesty had a huge impact on the language. But also the fact that now thousands of copies could be produced relatively quickly because they could be printed. Tyndale’s Bible was smuggled into England on ships, which were regularly searched for copies. Thomas More, the author of ‘Utopia’ was horrified and spoke about the shame of ploughboys being able to read the word of God. The head of the Catholic Church in London was so worried about the popularity of the translation that he bought the entire stock from Germany and burnt it. This only meant that Tyndale now had the money to produce more, of course.

Sadly, Tyndale was discovered and kidnapped from the town in Germany where he was living and working, taken to Amsterdam, tried by a Church court for doing the Devil’s work and, of course, found guilty. He was strangled and then his body was publicly burnt in 1536.

However, there were soon more political than religious considerations that decided the fate of Tyndale’s Bible.  The King, Henry VIII, was married to Katharine, a Spanish princess, niece to the powerful King of Spain, but after many years of marriage and many stillborn children, the couple had only managed to produce one daughter and Katharine was now past the age when she could have more children. There had never been an English queen who could keep the throne and Henry was staring the end of his dynasty in the face. He had to have a son! He applied to the Pope for permission to dissolve the marriage but this was refused – even a Pope could not afford to annoy the King of Spain! It was not long before Henry was seizing Catholic lands, burning priests and setting up his own Church of England …. which, of course, needed English Bibles. Too late to save Tyndale though. But the effects were felt across the land and nowhere more so than on the language!

Only a few decades later, the first Queen Elizabeth, a second daughter of Henry VIII’s , and a poet herself, was encouraging the arts.

The King, Henry VIII, was married to Katharine, a Spanish princess, niece to the powerful King of Spain, but after many years of marriage and many stillborn children, the couple had only managed to produce one daughter and Katharine was now past the age when she could have more children. There had never been an English queen who could keep the throne and Henry was staring the end of his dynasty in the face. He had to have a son! He applied to the Pope for permission to dissolve the marriage but this was refused – even a Pope could not afford to annoy the King of Spain! It was not long before Henry was seizing Catholic lands, burning priests and setting up his own Church of England …. which, of course, needed English Bibles. Too late to save Tyndale though. But the effects were felt across the land and nowhere more so than on the language!

Only a few decades later, the first Queen Elizabeth, a second daughter of Henry VIII’s , and a poet herself, was encouraging the arts.  Thomas Kidd, Kit Marlowe and William Shakespeare, among many others, were writing plays to entertain the public. And what plays they were! These dramatists’ use of language, their originality, their creativity, electrified their audiences and changed English forever. You see, English was beginning to take on a recognized standard but the process was new enough to allow change still to take place!

With England’s growing navy and trade, new words were also entering the language: ‘ketchup’ from Malaysia; ‘lemon’, ‘orange’, ‘tomato’, ‘potato’ and ‘banana’ from Spanish; ‘yoghurt’ from Turkish; ‘curry’ from India, ‘alcohol’ and ‘coffee’ from Arabic, not to mention ‘tobacco’ and ‘chocolate’ from the Americas. These were not only new foods arriving in the English kitchen but new words in the language too. And the ships’ crews – a word from French – brought us some more colourful words and phrases too – the F word came from Dutch sailors at around this time, along with ‘bugger’, ‘shit’ and ‘crap’.

And, so, English began to take a recognized and standard shape. There were still changes to come but these were to do with science, medicine and control of the language, rather than innovation.

If you want to watch some videos on this topic, you can click on the links to YouTube videos below.

If you want to answer questions on this article to test how much you understand, you can click on the green box: Finished Reading?

Videos:

1. John Wycliffe: Church History in Three Minutes (3:54)

2. The Reformers: John Wycliffe (1:00)

3. Wycliffe Bible Translators - who we are (1:36)

4. William Tyndale Bible of 1534 (2:46)

5. Tyndale Bible to go on Display at St Paul's Cathedral (2:01)

6. William Tyndale (2:07)

Thomas Kidd, Kit Marlowe and William Shakespeare, among many others, were writing plays to entertain the public. And what plays they were! These dramatists’ use of language, their originality, their creativity, electrified their audiences and changed English forever. You see, English was beginning to take on a recognized standard but the process was new enough to allow change still to take place!

With England’s growing navy and trade, new words were also entering the language: ‘ketchup’ from Malaysia; ‘lemon’, ‘orange’, ‘tomato’, ‘potato’ and ‘banana’ from Spanish; ‘yoghurt’ from Turkish; ‘curry’ from India, ‘alcohol’ and ‘coffee’ from Arabic, not to mention ‘tobacco’ and ‘chocolate’ from the Americas. These were not only new foods arriving in the English kitchen but new words in the language too. And the ships’ crews – a word from French – brought us some more colourful words and phrases too – the F word came from Dutch sailors at around this time, along with ‘bugger’, ‘shit’ and ‘crap’.

And, so, English began to take a recognized and standard shape. There were still changes to come but these were to do with science, medicine and control of the language, rather than innovation.

If you want to watch some videos on this topic, you can click on the links to YouTube videos below.

If you want to answer questions on this article to test how much you understand, you can click on the green box: Finished Reading?

Videos:

1. John Wycliffe: Church History in Three Minutes (3:54)

2. The Reformers: John Wycliffe (1:00)

3. Wycliffe Bible Translators - who we are (1:36)

4. William Tyndale Bible of 1534 (2:46)

5. Tyndale Bible to go on Display at St Paul's Cathedral (2:01)

6. William Tyndale (2:07)

Greek and religion by priests), in politics (where many government ministers and even rulers of some countries were priests), even in social life. In fact, it was not just advisable for the English to attend church on Sundays, it was mandatory.

It must come as a surprise, therefore, to learn that there was no English-language Bible that people could read to learn more about their religion. That book was only available in Latin and, even then, the priest in church on Sunday read it silently to himself. When he arrived at important parts of the text, a bell was rung so that the people would know those bits were especially holy, but they did not know what they were about. Why, one has to ask, if God was such an essential part of people’s lives, were they not allowed to read the book?

The answer lies in the fact that the authority of the Church required that both a foreign language and a priest had to stand between God’s word, on one hand, and the people on the other. How else could the Church control the people and influence the King and national policy? The arrangement generally worked well for the ruling class as its interests and those of the powerful and incredibly wealthy Church went hand in hand.

Yet, all this was about to change and largely because of one man, John Wycliffe, himself a priest. He believed that every farm boy should have the opportunity to read Christian scriptures for himself. So, in 1380, he began a translation of the

Greek and religion by priests), in politics (where many government ministers and even rulers of some countries were priests), even in social life. In fact, it was not just advisable for the English to attend church on Sundays, it was mandatory.

It must come as a surprise, therefore, to learn that there was no English-language Bible that people could read to learn more about their religion. That book was only available in Latin and, even then, the priest in church on Sunday read it silently to himself. When he arrived at important parts of the text, a bell was rung so that the people would know those bits were especially holy, but they did not know what they were about. Why, one has to ask, if God was such an essential part of people’s lives, were they not allowed to read the book?

The answer lies in the fact that the authority of the Church required that both a foreign language and a priest had to stand between God’s word, on one hand, and the people on the other. How else could the Church control the people and influence the King and national policy? The arrangement generally worked well for the ruling class as its interests and those of the powerful and incredibly wealthy Church went hand in hand.

Yet, all this was about to change and largely because of one man, John Wycliffe, himself a priest. He believed that every farm boy should have the opportunity to read Christian scriptures for himself. So, in 1380, he began a translation of the  Bible from Latin – with many friends and, of course, in secret because what he was doing was illegal. Two years later, the work was complete and then copied out by hand – hundreds and thousands of times – in small editions so that it could be hidden in people’s pockets. Of course, the Church determined in 1382 that the book was the Devil’s work and that anybody reading it should be executed and would certainly go to Hell. The unfortunate John Wycliffe had a stroke and died two years later but a group of men – called Lollards – continued to copy out his Bible and distribute it to as many people as they could, often facing death by fire themselves as a punishment. Wycliffe’s body was dug up in 1428 and burnt, in fact, as a reminder to the people that he was damned for eternity.

But what can we say about the effects that Wycliffe’s Bible had on the development of English? Actually, it seems that the man who went to an early grave for his belief that every Englishman should be able to read God’s word in his own language was actually rather afraid of his task. His Bible introduced more than 1,000 Latin words into English: words like: barbarian, birthday, crime, frying pan, humanity, pollute, madness and communicate, city, justice, profession & suddenly – none of which had ever been used in English before. Worse still, Wycliffe transliterated Latin grammar into English in such phrases as “I am a God jealous and vengeful”, putting adjectives after ‘God’, just as the Romans did. It was as if he were frightened of moving too far away from the Latin, as if he believed God might use that language.

Bible from Latin – with many friends and, of course, in secret because what he was doing was illegal. Two years later, the work was complete and then copied out by hand – hundreds and thousands of times – in small editions so that it could be hidden in people’s pockets. Of course, the Church determined in 1382 that the book was the Devil’s work and that anybody reading it should be executed and would certainly go to Hell. The unfortunate John Wycliffe had a stroke and died two years later but a group of men – called Lollards – continued to copy out his Bible and distribute it to as many people as they could, often facing death by fire themselves as a punishment. Wycliffe’s body was dug up in 1428 and burnt, in fact, as a reminder to the people that he was damned for eternity.

But what can we say about the effects that Wycliffe’s Bible had on the development of English? Actually, it seems that the man who went to an early grave for his belief that every Englishman should be able to read God’s word in his own language was actually rather afraid of his task. His Bible introduced more than 1,000 Latin words into English: words like: barbarian, birthday, crime, frying pan, humanity, pollute, madness and communicate, city, justice, profession & suddenly – none of which had ever been used in English before. Worse still, Wycliffe transliterated Latin grammar into English in such phrases as “I am a God jealous and vengeful”, putting adjectives after ‘God’, just as the Romans did. It was as if he were frightened of moving too far away from the Latin, as if he believed God might use that language. But more general use of English had another powerful supporter in the early 15th century. In 1417, nine years before Wycliffe’s corpse was dug up and burnt, King Henry V, fighting a war in France, sent messages back to London in English, the first time a king had used his own language in writing, although his father, Henry IV – you might remember from our first lecture on English – had started to speak the tongue in his court. That first written message might not seem so important to us but where the king led the way, others followed and, very soon, all official documents and communications were written in English.

Of course, until the early 15th century, there had been no need to make rules about spelling English. As an example, in the north of the country, the word ‘church’ was actually called ‘kirk’ but could be spelled: kirk, kyrke, kyrk, kerk, kirc and kurke.

But more general use of English had another powerful supporter in the early 15th century. In 1417, nine years before Wycliffe’s corpse was dug up and burnt, King Henry V, fighting a war in France, sent messages back to London in English, the first time a king had used his own language in writing, although his father, Henry IV – you might remember from our first lecture on English – had started to speak the tongue in his court. That first written message might not seem so important to us but where the king led the way, others followed and, very soon, all official documents and communications were written in English.

Of course, until the early 15th century, there had been no need to make rules about spelling English. As an example, in the north of the country, the word ‘church’ was actually called ‘kirk’ but could be spelled: kirk, kyrke, kyrk, kerk, kirc and kurke.  Yet, the printer worried so much about consistency of spelling that he expressed his concerns in writing… and not only about spelling but also grammar. Should he adopt ‘doth’ or ‘does’, for instance? The authors he was publishing often used both interchangeably but, clearly, a single form was preferable.

We can see, therefore, that there were a variety of influences on the development of written English: religious ones because translating the Bible from Latin meant deciding about precise meanings of words and grammatical forms; the legal and socio-political necessity for conformity to standardized grammar and spelling; and, finally, technological developments – the printing press – that required decisions about syntax and lexis.

And then, in the sixteenth century, everything was turned upside down once again. This was the age of William Tyndale and William Shakespeare, the two men who did more to shape the quality of English language than any others. First, Tyndale, in 1524, started to translate the Bible – he moved to Germany to be able to do so without fear of imprisonment – but he worked from the original Hebrew and Greek versions (rather than Wycliffe’s Latin one). The beauty of Tyndale’s English, his evident care that each word and phrase expressed not just the meaning of God’s message but also its majesty had a huge impact on the language. But also the fact that now thousands of copies could be produced relatively quickly because they could be printed. Tyndale’s Bible was smuggled into England on ships, which were regularly searched for copies. Thomas More, the author of ‘Utopia’ was horrified and spoke about the shame of ploughboys being able to read the word of God. The head of the Catholic Church in London was so worried about the popularity of the translation that he bought the entire stock from Germany and burnt it. This only meant that Tyndale now had the money to produce more, of course.

Sadly, Tyndale was discovered and kidnapped from the town in Germany where he was living and working, taken to Amsterdam, tried by a Church court for doing the Devil’s work and, of course, found guilty. He was strangled and then his body was publicly burnt in 1536.

However, there were soon more political than religious considerations that decided the fate of Tyndale’s Bible.

Yet, the printer worried so much about consistency of spelling that he expressed his concerns in writing… and not only about spelling but also grammar. Should he adopt ‘doth’ or ‘does’, for instance? The authors he was publishing often used both interchangeably but, clearly, a single form was preferable.

We can see, therefore, that there were a variety of influences on the development of written English: religious ones because translating the Bible from Latin meant deciding about precise meanings of words and grammatical forms; the legal and socio-political necessity for conformity to standardized grammar and spelling; and, finally, technological developments – the printing press – that required decisions about syntax and lexis.

And then, in the sixteenth century, everything was turned upside down once again. This was the age of William Tyndale and William Shakespeare, the two men who did more to shape the quality of English language than any others. First, Tyndale, in 1524, started to translate the Bible – he moved to Germany to be able to do so without fear of imprisonment – but he worked from the original Hebrew and Greek versions (rather than Wycliffe’s Latin one). The beauty of Tyndale’s English, his evident care that each word and phrase expressed not just the meaning of God’s message but also its majesty had a huge impact on the language. But also the fact that now thousands of copies could be produced relatively quickly because they could be printed. Tyndale’s Bible was smuggled into England on ships, which were regularly searched for copies. Thomas More, the author of ‘Utopia’ was horrified and spoke about the shame of ploughboys being able to read the word of God. The head of the Catholic Church in London was so worried about the popularity of the translation that he bought the entire stock from Germany and burnt it. This only meant that Tyndale now had the money to produce more, of course.

Sadly, Tyndale was discovered and kidnapped from the town in Germany where he was living and working, taken to Amsterdam, tried by a Church court for doing the Devil’s work and, of course, found guilty. He was strangled and then his body was publicly burnt in 1536.

However, there were soon more political than religious considerations that decided the fate of Tyndale’s Bible.  The King, Henry VIII, was married to Katharine, a Spanish princess, niece to the powerful King of Spain, but after many years of marriage and many stillborn children, the couple had only managed to produce one daughter and Katharine was now past the age when she could have more children. There had never been an English queen who could keep the throne and Henry was staring the end of his dynasty in the face. He had to have a son! He applied to the Pope for permission to dissolve the marriage but this was refused – even a Pope could not afford to annoy the King of Spain! It was not long before Henry was seizing Catholic lands, burning priests and setting up his own Church of England …. which, of course, needed English Bibles. Too late to save Tyndale though. But the effects were felt across the land and nowhere more so than on the language!

Only a few decades later, the first Queen Elizabeth, a second daughter of Henry VIII’s , and a poet herself, was encouraging the arts.

The King, Henry VIII, was married to Katharine, a Spanish princess, niece to the powerful King of Spain, but after many years of marriage and many stillborn children, the couple had only managed to produce one daughter and Katharine was now past the age when she could have more children. There had never been an English queen who could keep the throne and Henry was staring the end of his dynasty in the face. He had to have a son! He applied to the Pope for permission to dissolve the marriage but this was refused – even a Pope could not afford to annoy the King of Spain! It was not long before Henry was seizing Catholic lands, burning priests and setting up his own Church of England …. which, of course, needed English Bibles. Too late to save Tyndale though. But the effects were felt across the land and nowhere more so than on the language!

Only a few decades later, the first Queen Elizabeth, a second daughter of Henry VIII’s , and a poet herself, was encouraging the arts.  Thomas Kidd, Kit Marlowe and William Shakespeare, among many others, were writing plays to entertain the public. And what plays they were! These dramatists’ use of language, their originality, their creativity, electrified their audiences and changed English forever. You see, English was beginning to take on a recognized standard but the process was new enough to allow change still to take place!

With England’s growing navy and trade, new words were also entering the language: ‘ketchup’ from Malaysia; ‘lemon’, ‘orange’, ‘tomato’, ‘potato’ and ‘banana’ from Spanish; ‘yoghurt’ from Turkish; ‘curry’ from India, ‘alcohol’ and ‘coffee’ from Arabic, not to mention ‘tobacco’ and ‘chocolate’ from the Americas. These were not only new foods arriving in the English kitchen but new words in the language too. And the ships’ crews – a word from French – brought us some more colourful words and phrases too – the F word came from Dutch sailors at around this time, along with ‘bugger’, ‘shit’ and ‘crap’.

And, so, English began to take a recognized and standard shape. There were still changes to come but these were to do with science, medicine and control of the language, rather than innovation.

If you want to watch some videos on this topic, you can click on the links to YouTube videos below.

If you want to answer questions on this article to test how much you understand, you can click on the green box: Finished Reading?

Videos:

1. John Wycliffe: Church History in Three Minutes (3:54)

2. The Reformers: John Wycliffe (1:00)

3. Wycliffe Bible Translators - who we are (1:36)

4. William Tyndale Bible of 1534 (2:46)

5. Tyndale Bible to go on Display at St Paul's Cathedral (2:01)

6. William Tyndale (2:07)

Thomas Kidd, Kit Marlowe and William Shakespeare, among many others, were writing plays to entertain the public. And what plays they were! These dramatists’ use of language, their originality, their creativity, electrified their audiences and changed English forever. You see, English was beginning to take on a recognized standard but the process was new enough to allow change still to take place!

With England’s growing navy and trade, new words were also entering the language: ‘ketchup’ from Malaysia; ‘lemon’, ‘orange’, ‘tomato’, ‘potato’ and ‘banana’ from Spanish; ‘yoghurt’ from Turkish; ‘curry’ from India, ‘alcohol’ and ‘coffee’ from Arabic, not to mention ‘tobacco’ and ‘chocolate’ from the Americas. These were not only new foods arriving in the English kitchen but new words in the language too. And the ships’ crews – a word from French – brought us some more colourful words and phrases too – the F word came from Dutch sailors at around this time, along with ‘bugger’, ‘shit’ and ‘crap’.

And, so, English began to take a recognized and standard shape. There were still changes to come but these were to do with science, medicine and control of the language, rather than innovation.

If you want to watch some videos on this topic, you can click on the links to YouTube videos below.

If you want to answer questions on this article to test how much you understand, you can click on the green box: Finished Reading?

Videos:

1. John Wycliffe: Church History in Three Minutes (3:54)

2. The Reformers: John Wycliffe (1:00)

3. Wycliffe Bible Translators - who we are (1:36)

4. William Tyndale Bible of 1534 (2:46)

5. Tyndale Bible to go on Display at St Paul's Cathedral (2:01)

6. William Tyndale (2:07)