Course description

English – A Language Created by Borrowing from Others

The history of the English language is also the history of the British Isles, as different invaders arrived for a thousand years between the decades before the birth of Christ and the last conquest of England in 1066. In the eleven hundred years between, the Romans brought Latin, tribes called the Angles, Jutes and Saxons carried with them their Germanic language, the Vikings used Old Norse from Scandinavia, and another Viking whose family had long settled in France, William the Conqueror, beat the last of the Saxon kings on the south coast of England in 1066 and introduced French as the language of the court, government and the law.

But English did not die out as each new band of invaders arrived and imported their own tongue. Rather it assimilated the new vocabulary (and sometimes grammar) of these new languages, adding layer upon layer of shades of meaning so that modern English eventually became a very rich and subtle tongue.

But English did not die out as each new band of invaders arrived and imported their own tongue. Rather it assimilated the new vocabulary (and sometimes grammar) of these new languages, adding layer upon layer of shades of meaning so that modern English eventually became a very rich and subtle tongue.

Because it was an island, England developed a strong navy for trade, so new words from Arabic, Sanskrit, European languages and others were also added, making English a confusing mixture of words with many different influences. This affected the spelling of the language too, creating many, many problems for students trying to learn it, as you are today.

This is the story of English and its development over the last fifteen hundred years but it is also the story of the many different people who have lived on the island, as it is impossible to talk about one without the other.

So, let’s go back to the arrival of Julius Caesar in England in 55 BC, the Roman whose family name has now been adapted to mean ‘King’ in German (Kaiser) and in Russian (Czar). He was already the most powerful man in the Roman Empire, whose territory he had greatly enlarged by conquering Gaul (now France) in a bloody seven-year war. In fact, Caesar’s only reason for attacking Britain was that the Celtic people living there were helping his enemies in Gaul. As soon as he chose an English Celtic king friendly to Rome, he left again. It had to wait nearly another century for the Emperor Claudius in 43 AD to invade once again and make Britain a part of his Roman Empire. This was a government that was to rule all of England and most of Wales for another four hundred years and sometimes even the southern areas of Scotland during that period.

The people of Britain spoke a variety of Celtic languages when the Romans invaded but Latin became the language of government and of the ruling class, which never learnt to speak the local dialects. The Romans were responsible for making many cities, including London, Manchester and York, where Latin was needed for business. But, when the Empire collapsed in the fifth century, probably because of economic decline and raids by German tribes, these cities were abandoned – although they came to life again years later. Not so, the Latin language! The British once again spoke the Celtic they had continued to use throughout the four centuries of Roman occupation. But all that was soon to change!

The people of Britain spoke a variety of Celtic languages when the Romans invaded but Latin became the language of government and of the ruling class, which never learnt to speak the local dialects. The Romans were responsible for making many cities, including London, Manchester and York, where Latin was needed for business. But, when the Empire collapsed in the fifth century, probably because of economic decline and raids by German tribes, these cities were abandoned – although they came to life again years later. Not so, the Latin language! The British once again spoke the Celtic they had continued to use throughout the four centuries of Roman occupation. But all that was soon to change!

Already by the time the Romans left Britain in 410, there had been attacks on rural communities by Germanic tribes but, as the decades passed, more and more of these decided to stay. They came from three main tribes: the Angles (who gave their name to England), the Jutes and Saxons. At first, the Celts tried to make treaties with these tribes who settled in the north of England, offering food and other provisions in return for them protecting the Celts from raids and attacks by the Scottish Picts. But this did not satisfy the Germanic tribes for long. They went to war with the Celts, pushing them further and further to the west and the north – to modern Wales and Scotland – and ruled the land themselves in different kingdoms. In fact, the name of Wales comes from a Saxon word, ‘welas’, meaning ‘foreigner’ but also ‘slave’.

But, even if we feel sorry for the Celts, it was the Anglo-Saxon tribes which made the English language. For example, nearly half of all words in modern English originate in this Germanic linguistic family and a much, much higher proportion of everyday vocabulary. Let’s take something as basic as family – a word from Latin, by the way – as an illustration: ‘son’, ‘daughter’, ‘friend’, ‘home’, ‘house’, ‘room’, ‘ground’ and ‘land’ all come from the Anglo-Saxons. Then, there are far more words for food and weather – see if you can guess the modern translations of these Anglo-Saxon words for instance: bûter, brea, tsiis, see, stoarm, frost, friiz, mist, and so on. Verbs like ‘go’, ‘come’, ‘see’, ‘sing’, speak’, ‘like’ and ‘love’ all come from Anglo-Saxon too – in fact, just about every irregular verb originates there.

But, even if we feel sorry for the Celts, it was the Anglo-Saxon tribes which made the English language. For example, nearly half of all words in modern English originate in this Germanic linguistic family and a much, much higher proportion of everyday vocabulary. Let’s take something as basic as family – a word from Latin, by the way – as an illustration: ‘son’, ‘daughter’, ‘friend’, ‘home’, ‘house’, ‘room’, ‘ground’ and ‘land’ all come from the Anglo-Saxons. Then, there are far more words for food and weather – see if you can guess the modern translations of these Anglo-Saxon words for instance: bûter, brea, tsiis, see, stoarm, frost, friiz, mist, and so on. Verbs like ‘go’, ‘come’, ‘see’, ‘sing’, speak’, ‘like’ and ‘love’ all come from Anglo-Saxon too – in fact, just about every irregular verb originates there.

If we look at Celtic words, on the other hand, we will see very, very little influence on modern English. Most of these are found in the names of towns, like Birmingham (‘-ham’ meant ‘farm’) and Brighton (‘-ton’ meant ‘people’). Today, if we listen to Welsh Gaelic or Cornish or Scottish Gaelic – all areas where the Germanic tribes did not settle, by the way – we can see how hugely different the words in these languages are from modern English.

But it was not only with vocabulary that Anglo-Saxon made its mark on English: it also provided the basis for its grammar. For instance, prepositions like ‘in, ‘on’, ‘into’, ‘from’ and ‘by’ and most others come from Germanic languages, which also often put these before nouns, not after them, as they do in Celtic.

But it was not only with vocabulary that Anglo-Saxon made its mark on English: it also provided the basis for its grammar. For instance, prepositions like ‘in, ‘on’, ‘into’, ‘from’ and ‘by’ and most others come from Germanic languages, which also often put these before nouns, not after them, as they do in Celtic.

For the Celts, the end came in 491, when a community of people locked themselves into the Roman-built Pevensey Castle to protect themselves against invading Germanic tribes but were slaughtered anyway, the Celts’ fight for their own land was lost. They escaped west and north to the extremes of the island.

The Angles, Jutes and Saxons made their homes under their own kings in Essex, Wessex, Kent, Sussex, East Anglia and Northumberland. They inter-married with Celts and farmed the land peacefully. Their language, we have already noted, was enormously important to the development of modern English. But it was largely an oral one. There was – it is true – an alphabet made of straight lines or ‘runes’, which could communicate basic ideas but the carvings that we can still see today are usually formulaic – not changing much from one rock, where they are carved, to another.

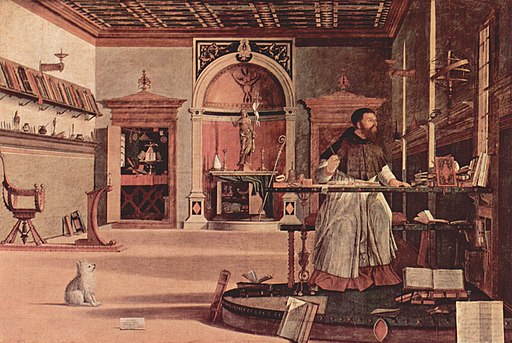

About a hundred years after the massacre at Pevensey, St. Augustine arrived in Kent from Rome, bringing the message of Christianity with him – to be precise, in 597. Meanwhile, in the north of England, monks from Ireland were converting the people from their old Germanic gods (which gave us the names of most days of the week, by the way: Wodin for Wednesday, Thor for Thursday, and so on) to Christianity. They built a beautiful monastery on the tiny island of Lindisfarne and wrote by hand a copy of the Gospels. Bede, a monk at a northern town called Jarrow, wrote ‘A History of the English Church and People’, full of miracles happening every day.

About a hundred years after the massacre at Pevensey, St. Augustine arrived in Kent from Rome, bringing the message of Christianity with him – to be precise, in 597. Meanwhile, in the north of England, monks from Ireland were converting the people from their old Germanic gods (which gave us the names of most days of the week, by the way: Wodin for Wednesday, Thor for Thursday, and so on) to Christianity. They built a beautiful monastery on the tiny island of Lindisfarne and wrote by hand a copy of the Gospels. Bede, a monk at a northern town called Jarrow, wrote ‘A History of the English Church and People’, full of miracles happening every day.

And what was the language they used? Latin, of course, the language of the Roman Catholic Church. It gave us many words linked to religion at this time but, more importantly, it gave the English an alphabet – the same one we use today, more or less. The shapes of the letters were no longer made up of straight lines that could easily be carved into stone, but were rounded because they were written in pen and ink on animal skins.

And what was the language they used? Latin, of course, the language of the Roman Catholic Church. It gave us many words linked to religion at this time but, more importantly, it gave the English an alphabet – the same one we use today, more or less. The shapes of the letters were no longer made up of straight lines that could easily be carved into stone, but were rounded because they were written in pen and ink on animal skins.

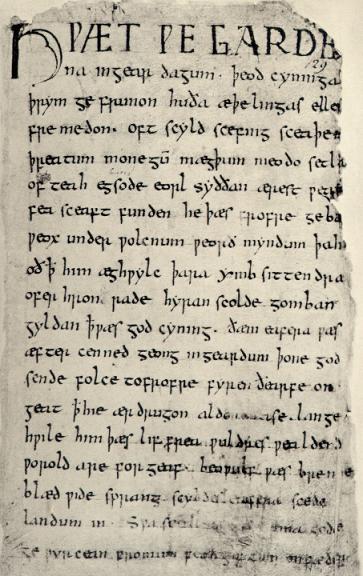

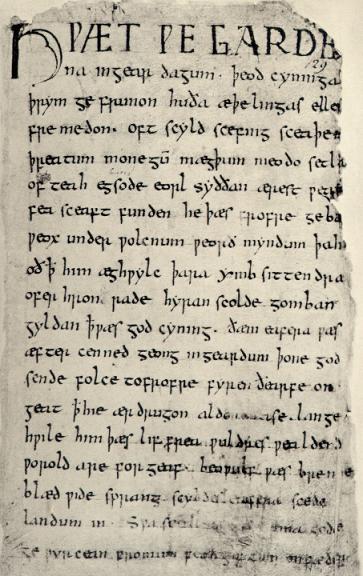

Soon, the Latin alphabet was used to transcribe Anglo-Saxon – or, as we sometimes call it – Old English as well. This was a hugely important move because it meant that educated people did not need to record history or ideas in Latin, but could do so in their own language. In this way, we get The Anglo Saxon Chronicle from the late ninth century and the first poem in English – or, indeed, in any European language – Beowulf, probably written from oral accounts sometime between the eighth and tenth centuries. It is a magnificent achievement, a story of the bravery of a Germanic hero – Beowulf, of course – battling against a dragon, the enemy of all Anglo Saxons, called Grendel. (By the way, both Arabic and Chinese had written poetry in the eighth century and, so, you must not imagine that Old English was the first literary language – just the first of any European one!)

Seamus Heaney, an Irish poet and winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1995, translated ‘Beowulf’ and talked about the poetic strength of Old English, saying that it was ideal for describing action and telling stories. He noted that, like German even today, words could be put together into compound forms to make new meanings. A grave, for example, translates from two words in Old English: bone and house; and the musical instrument, the harp, is rendered by ‘happiness’ and ‘wood’, the material it was made from; a shield was a ‘war board’. You get the point.

Seamus Heaney, an Irish poet and winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1995, translated ‘Beowulf’ and talked about the poetic strength of Old English, saying that it was ideal for describing action and telling stories. He noted that, like German even today, words could be put together into compound forms to make new meanings. A grave, for example, translates from two words in Old English: bone and house; and the musical instrument, the harp, is rendered by ‘happiness’ and ‘wood’, the material it was made from; a shield was a ‘war board’. You get the point.

Yet, the survival of Anglo-Saxon was not always assured. From the late eighth century, the Vikings – seamen from Scandinavia – were ever-ready to leave their icy homeland and rob settlements all over Europe, including England, in their (technologically advanced) ships. They typically attacked churches, monasteries and small towns on the coast, stole everything they could carry away, killed the inhabitants, and returned to Norway, Denmark or Sweden. In 793, these Vikings burnt the monastery of Lindisfarne, a small, undefended island, and with it, all its books. The following year, Jarrow went the same way. Bede had studied and written there and the library at Jarrow was one of the finest in Europe and also a place where Old English was being written. To the Vikings, it was just an easy target for theft.

All Europe was in shock at this pointless destruction – probably just as the Celts had been when the Angles, Jutes and Saxons had arrived three centuries before. Yet, by 865, when the Vikings attacked East Anglia and settled there, most of the north and east of England was in their hands. Only Wessex remained Anglo-Saxon.

In Wessex, Alfred was king – the only English monarch ever to be called ‘the Great’, by the way – and was in despair. His army had been beaten and he was forced to get shelter in a poor woman’s home, where he was blamed for not watching over the food she was preparing and allowing it to burn.

In Wessex, Alfred was king – the only English monarch ever to be called ‘the Great’, by the way – and was in despair. His army had been beaten and he was forced to get shelter in a poor woman’s home, where he was blamed for not watching over the food she was preparing and allowing it to burn.

Alfred realized that the English language was dying out as a written form of communication. As priests were killed by the Vikings, their scholarship died with them. Their replacements were, perhaps, brave and faithful followers of Christianity but most could not understand Latin and were illiterate in that language and in Old English. In short, Old English was in a very similar position to Celtic at the end of the fifth century. As Norse spread across most of England, the language of the Anglo-Saxons was in great danger of dying out! It needed a champion …. And it found one in King Alfred.

Alfred became King of Wessex in 871 and of all Saxons in 886 and ruled for approximately twenty-eight years. However, during the first seven years of his reign, he was continually fighting the Danes (as the Vikings were, by then, known) in irregular guerilla warfare. It was only in 878 that he felt strong enough to make a call to arms among all the men in his kingdom. Four thousand joined him and fought a bloody battle against the Danes at a village called Eddington. Stories of the fighting vary but one thing is clear: Alfred won. The Viking leader, Guthrum, converted to Christianity and, most importantly, a border was drawn between ‘Danelaw’, north and east of London, and Wessex to the south and east. Nobody from either side was allowed to cross this line unless it was for trade. So, finally, a peace agreement was reached. When Anglo-Saxon and Dane met after 878 it was either to do business or to marry.

The peace accord left Alfred with time free to focus on education in his kingdom. He set up a school for his own children and those of his chiefs but many other children were allowed to attend as well. Schooling was in English and only changed to Latin at secondary level if a child was to become a priest. Tutors were called from other parts of England but also from mainland Europe. Interestingly, part of their job role was to teach the king himself. As Alfred said, he could not imagine a king who could not want to learn more.

Alfred also demanded translations from Latin to Old English of all the books he felt were important for educated men to be able to read. He also translated a few of these himself.

Alfred also demanded translations from Latin to Old English of all the books he felt were important for educated men to be able to read. He also translated a few of these himself.

By the time Alfred died in 899, English scholarship was once more on its feet.

But we must be careful not to think of the Dane and the Anglo-Saxon communities as entirely separate. Old Norse influenced Old English more than any other language. We can see this especially in those areas where they governed. For instance, surnames ending in ‘–son’ are from Scandinavian languages: Dixon, Johnson, Jackson, Dawson and so on. And then there are hundreds of words: score (skor), sky (sky), anger (angr), ball, (bole), die (dye), egg (eg), husband (hasbond), knife (knif), law (lore), root (rót), ugly (ugglir) and window (vindauga), for example. But Old Norse did more than just lend words to English: it simplified its grammar so that prepositions became more common and most plurals changed from ‘–en’ to ‘–s’.

But that is not to say that the Old English words died out. Rather, the Norse word existed alongside its English translation, perhaps with a slight change in meaning, although not always. So, ‘sick’ is Old English, ‘ill’ is from Norse, while ‘craft’ is the English version of the Norse ‘skill’. This, of course, made the language richer, although perhaps not as easy for students to learn!

However, English was to face a much greater threat only 167 years after Alfred’s death. The lord of Normandy (on the west coast of France), himself of Viking origin, claimed the throne of England in 1066 and attacked the last Saxon king, Harold, who died from an arrow in his eye, at Hastings, a seaside town. The exact spot of William’s victory and Harold’s defeat is now a small town called ‘Battle’, a French name.

Over the next three hundred years, no English king spoke the language of his people. Anglo-Saxon lords were killed, lost their lands or escaped to Europe. A few years after William became king, over half the land was given to only 190 of his supporters. At the ceremony (a French word) when William received the crown (another French word) on his throne (and yet another one!), the language spoken by the priest was Latin but the king spoke only French.

In the three hundred years that followed, Old English adopted maybe 10,000 French words! At first, these were often military: castle, enemy, army, soldier and guard. Soon, there were more social borrowings: peasant, servant, authority, prison, judge, jury, sentence, penalty and punishment. As we all know, French food is one of the most delicious in the world and their diet is very important to the French. It’s unsurprising, therefore, that the following vocabulary all originates in French: market, beef, mutton, pork, veal, salad, dinner, sausage, grape, lemon, orange, sugar, biscuit and cream as well as fry. By contrast, the words for farm animals remained English: cow, pig, sheep, calf, and so on.

As decade followed decade, more and more of the written English language disappeared. In 1154, the last of the Anglo Saxon Chronicles was penned. The language of the Church was firmly Latin and of government either that language or French. The social status of the English inhabitants was going down and down so that most farmers were now tied to the land – they were not slaves exactly, but they were not free either!

The greatest literature from this period of English history was written in Old French and only translated in 1485 into Middle English. By this time, Geoffrey Chaucer had already published his ‘Canterbury Tales’ in Middle English, as well as other works.

The greatest literature from this period of English history was written in Old French and only translated in 1485 into Middle English. By this time, Geoffrey Chaucer had already published his ‘Canterbury Tales’ in Middle English, as well as other works.

But spoken English survived, despite all this.

During the reign of Henry I, his wife Eleanor, was widely seen as one of the most cultured people in Europe. It was because of her that the idea of knighthood – seen in King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table – began to be linked to chivalry and charity. Until then, knights were not much more than armed and dangerous robbers who stole from the poor. Eleanor’s new ideals led to more words from French entering the English language: honour, chivalry, nobility, and so on.

Similarly, England became known in the early twelfth century as a major exporter of wool but the craftsmen were French and gathered together in enclaves in cities like Norwich in East Anglia, where they did business with local people, Hence, these words imported into English: commerce, partner, money, merchant and contract.

But once again, French vocabulary – just like Norse before it – did not replace English. Instead, new words from French existed side by side with Old English ones, having similar but not identical meanings. Look at these examples of words entering English for the first time in the thirteenth century: demand (ask), power (might), chamber (room), response & reply (answer), commence (begin) and liberty (freedom). Each has a different shade of meaning from its English synonym.

However, in 1206, King John, one of the most infamous monarchs in English history, lost his territory in France, Normandy. Until this time, the French in England, even if they, their fathers or grandfathers had never been to Normandy, saw it as their spiritual home – the place they belonged to. When it was gone, their attitude shifted so that they started to see England like that. They inter-married with English people for the first time and, so, homes became bi-lingual. French mothers would use English baby talk with their infants for the first time.

Then in the fourteenth century, the Black Death laid its icy hand on England, as it had so much of Europe. This led to a huge change in social class. Many French lords died and even more priests (who often cared for the dying or offered comfort to their (infected) relatives. As there were fewer workers, wages rose but property prices fell – after all, they were so many empty homes for sale. In short, the poor got richer and took on more important roles in society.

Then in the fourteenth century, the Black Death laid its icy hand on England, as it had so much of Europe. This led to a huge change in social class. Many French lords died and even more priests (who often cared for the dying or offered comfort to their (infected) relatives. As there were fewer workers, wages rose but property prices fell – after all, they were so many empty homes for sale. In short, the poor got richer and took on more important roles in society.

This led to important changes in use of language. In 1385, the language of the schoolroom became English until the age of 12, not Latin. Priests spoke in Church in their native tongue. Business was done in English from 1352 and all legal cases were tried in the language of the people from 1362, the same year as the most important government minister at the time, the Chancellor, addressed Members of Parliament in English. Finally, in 1399, King Henry IV gave his coronation speech in English – not French – the first time any monarch had done this since the tenth century.

Chaucer, the first great English writer, died in 1400, leaving behind him his work – all in Middle English. It was published on his new printing press, by William Caxton.

And with the printing press, modern English began to take shape. But that is a story for another day!

If you want to watch some videos on this topic, you can click on the links to YouTube videos below.

If you want to answer questions on this article to test how much you understand, you can click on the green box: Finished Reading?

Videos :

1. Julius Caesar (4:00)

2. The Celts (4:36)

3. Latin (19:00)

4. The Romans (3:27)

5. Claudius (2:00)

6. Angles, Jutes and Saxons (4:00)

7. Pevensey Castle (4:00)

8. St. Augustine (8:00)

9. Anglo-Saxon Chronicles (3:30)

10. Beowulf (5:00)

11. Lindisfarne (5:00)

12. Alfred the Great and the Vikings (7:00)

13. Harold (9:00)

14. William the Conqueror (12:00)

But English did not

But English did not  The people of Britain spoke a

The people of Britain spoke a  But, even if we feel sorry for the Celts, it was the Anglo-Saxon tribes which made the English language. For example, nearly half of all words in modern English

But, even if we feel sorry for the Celts, it was the Anglo-Saxon tribes which made the English language. For example, nearly half of all words in modern English  But it was not only with vocabulary that Anglo-Saxon made its mark on English: it also provided the basis for its grammar. For instance, prepositions like ‘in, ‘on’, ‘into’, ‘from’ and ‘by’ and most others come from Germanic languages, which also often put these before nouns, not after them, as they do in Celtic.

But it was not only with vocabulary that Anglo-Saxon made its mark on English: it also provided the basis for its grammar. For instance, prepositions like ‘in, ‘on’, ‘into’, ‘from’ and ‘by’ and most others come from Germanic languages, which also often put these before nouns, not after them, as they do in Celtic. About a hundred years after the

About a hundred years after the  And what was the language they used? Latin, of course, the language of the Roman Catholic Church. It gave us many words linked to religion at this time but, more importantly, it gave the English an alphabet – the same one we use today,

And what was the language they used? Latin, of course, the language of the Roman Catholic Church. It gave us many words linked to religion at this time but, more importantly, it gave the English an alphabet – the same one we use today,  Seamus Heaney, an Irish poet and winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1995, translated ‘Beowulf’ and talked about the poetic strength of Old English, saying that it was ideal for describing action and telling stories. He noted that, like German even today, words could be put together into

Seamus Heaney, an Irish poet and winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1995, translated ‘Beowulf’ and talked about the poetic strength of Old English, saying that it was ideal for describing action and telling stories. He noted that, like German even today, words could be put together into  In Wessex, Alfred was king – the only English

In Wessex, Alfred was king – the only English  Alfred also demanded translations from Latin to Old English of all the books he felt were important for educated men to be able to read. He also translated a few of these himself.

Alfred also demanded translations from Latin to Old English of all the books he felt were important for educated men to be able to read. He also translated a few of these himself. The greatest literature from this period of English history was written in Old French and only translated in 1485 into Middle English. By this time, Geoffrey Chaucer had already published his ‘Canterbury Tales’ in Middle English, as well as other works.

The greatest literature from this period of English history was written in Old French and only translated in 1485 into Middle English. By this time, Geoffrey Chaucer had already published his ‘Canterbury Tales’ in Middle English, as well as other works. Then in the fourteenth century, the Black Death laid its icy hand on England, as it had so much of Europe. This led to a huge change in social class. Many French lords died and even more priests (who often cared for the dying or offered comfort to their (infected) relatives. As there were fewer workers, wages rose but property prices fell – after all, they were so many empty homes for sale. In short, the poor got richer and took on more important roles in society.

Then in the fourteenth century, the Black Death laid its icy hand on England, as it had so much of Europe. This led to a huge change in social class. Many French lords died and even more priests (who often cared for the dying or offered comfort to their (infected) relatives. As there were fewer workers, wages rose but property prices fell – after all, they were so many empty homes for sale. In short, the poor got richer and took on more important roles in society.