Course description

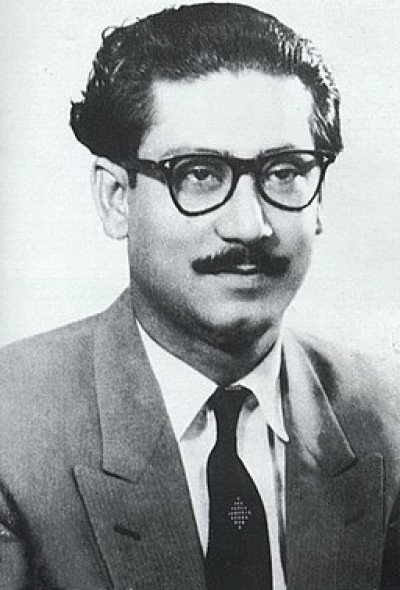

A New York Times Interview with Sheikh Mujibur

What it was like never to know if that day was your last

Here is an interview with Sheikh Mujib, written by Sydney H. Shanberg and published by The New York Times on 18th January, 1972. It describes Bangabondhu’s arrest and journey to West Pakistan, where he was jailed and lived in daily fear of execution. My thanks to former UGC Chairman, and former Vice-Chancellor of Chittagong University, now Professor of Business at ULAB, Abdul Mannan, for sending it to me for the General Education course.

He kissed his weeping wife and children good‐bye, telling them what they knew too well—that he might never return. Then the West Pakistani soldiers pushed him down the stairs, hitting him from behind with their rifles. He reached their jeep and then, in a reflex of habit and defiance, said: “I have forgotten my pipe and tobacco. I must have my pipe and tobacco!”

He kissed his weeping wife and children good‐bye, telling them what they knew too well—that he might never return. Then the West Pakistani soldiers pushed him down the stairs, hitting him from behind with their rifles. He reached their jeep and then, in a reflex of habit and defiance, said: “I have forgotten my pipe and tobacco. I must have my pipe and tobacco!”

The soldiers were taken aback, but they took him back into the house, where his wife handed him the pipe and tobacco. He was then driven off to nine and a half months of imprisonment by the Pakistani Government for his leadership of the Ben Gali autonomy movement in East Pakistan.

That was a piece of his narrative today as Sheikh Mujibur Rahman related for the first time the full story of his arrest and imprisonment and narrow escapes from death—and his release a week ago.

Relaxed and with no bitterness, and sometimes laughing at his good luck, the Prime Minister of the newly proclaimed nation of Bangladesh talked in fluent English with a handful of American newspaper reporters. He leaned back on a sofa in the sitting room of the official residence of his captor, former President Agha Mohammad Yahya Khan of Pakistan, who is himself now under house arrest in West Pakistan, and started from the beginning—the night of March 25.

Relaxed and with no bitterness, and sometimes laughing at his good luck, the Prime Minister of the newly proclaimed nation of Bangladesh talked in fluent English with a handful of American newspaper reporters. He leaned back on a sofa in the sitting room of the official residence of his captor, former President Agha Mohammad Yahya Khan of Pakistan, who is himself now under house arrest in West Pakistan, and started from the beginning—the night of March 25.

His pipe and tobacco lay on a coffee table in front of him. He said he had learned of a plot by the Pakistani military regime to kill him and blame it on the Bengalis. “Whenever I came out of the house,” he said “they were going to throw a grenade at my car and then say Bengali extremists did it and that was why the army had to move in and take action against my people. I decided I must stay in my own house and let them kill me there, so that everybody would know they had killed me, and my blood would purify my people.”

That day, March 25, with reports growing that an army crackdown was imminent against the popularly elected movement aiming to end the long West Pakistani exploitation of the more populous eastern region, Sheikh Mujib had sent his oldest son, Kamal, and his two daughters into hiding. His wife, keeping their youngest son, Russell, close by her, refused to leave their modest two‐storey house in the Dhanmondi section of Dhaka.

Unknown to them, their middle son, Jamal, was still in the house, sleeping in his room.

By 10 P.M. Sheikh Mujib had received word that West Pakistani troops were going to attack the civilian population. A few minutes later troops surrounded his house and a mortar shell exploded nearby.

He had made some secret preparations for such an attack. At 10.30 P.M. he called a secret headquarters in Chittagong, the south-eastern port city, and dictated a last message to his people, which was recorded and later broadcast by secret transmitter.

The gist of the broadcast was that they should resist any army attack and fight on regardless of what might happen to their leader. He also spoke of independence for the 75 million people of East Pakistan.

The gist of the broadcast was that they should resist any army attack and fight on regardless of what might happen to their leader. He also spoke of independence for the 75 million people of East Pakistan.

Sheikh Mujib explained that, after sending his message, he ordered away the men of the East Pakistan Rifles, a para-military unit, and of the Awami League, his political party, who were guarding him.

The West Pakistani attack throughout the city began at about 11 P.M. and quickly increased in intensity. The troops began firing into Sheikh Mujib's house between midnight and 1 A.M. He pushed his wife and two children into his room upstairs and they all got clown on the floor as the bullets hurried over head.

The troops soon broke into the house, killing a watchman who had refused to leave, and stormed up the stairs. Sheikh Mujib said he opened the door of the room and faced them saying: “Stop shooting! Stop shooting! Why are you shooting? If you want to shoot me, then shoot me; here I am, but why are you shooting my people and my children?”

A major halted the men and told them there would be no more shooting. He told Sheikh Mujib he was being arrested and, at his request, allowed him a few moments to say his farewells. He kissed each member of the family and, he recalled, said to them: “They may kill me. I may never see you again. But my people will be free some day and my soul will see it and be happy.”

He was driven to the National Assembly building, “where I was given a chair.”

“Then they offered me tea,” he recalled. “I said, ‘That's wonderful. Wonderful situation. This is the best time of my life to have tea.’”

After a while he was taken to “a dark and dirty room” at a school in the military cantonment. For six days he spent his days in that room and his nights—midnight to 6 A.M.— in a room in the residence of the martial‐law administrator, Lieut. Gen. Tikka Khan, the man the Bengalis consider most responsible for the military action, in which hundreds of thousands of Bengalis were tortured and killed.

On April 1, Sheikh Mujib said, he was flown to Rawalpindi, in West Pakistan—separated from East Pakistan by over a thousand miles of Indian territory—and then moved to Mianwali Prison and put in the condemned cell. He passed the next nine months alternating between that prison and two others, at Lyallpur and at Sahiwal, all in the northern part of Punjab Province. The military Government began proceedings against him on 12 charges, six of which carried the death penalty. One was “waging war against Pakistan.”

Sheikh Mujib, who is a lawyer, knew he had no chance of acquittal, so he tried delaying tactics. “I was playing a game with them too,” he said, smiling. “I was trying to get some time.”

Sheikh Mujib, who is a lawyer, knew he had no chance of acquittal, so he tried delaying tactics. “I was playing a game with them too,” he said, smiling. “I was trying to get some time.”

At first he demanded to be defended by A. K. Brohi, West Pakistan's most eminent lawyer, who is respected by all sides. Mr. Brohi was finally allowed to prepare the defense. After several months the trial opened at Lyallpur, at which time Sheikh Mujib did a sudden about‐face, announcing that he wanted to enter no defence, so Mr. Brohi could be sent home.

President Yahya Khan gave a new martial‐law order saying that Sheikh Mujib had to have a lawyer whether he wanted one or not. “You see how they were ‘protecting my rights,’” Sheikh Mujib said. “They just wanted a certificate to hang me.”

The trial ended on Dec. 4 — the second day of the Indian-Pakistani war that grew out of the East Pakistan crisis and ended in an Indian victory and East Pakistan's independence under the name Bangladesh.

“Yahya called all the members of the military court to Rawalpindi to write up their findings in a hurry,” Sheikh Mujib said, “but then he got busy with the war.”

The verdict, which might be ridiculous in the middle of a full scale conflict, was never announced, but on Dec. 7 Sheikh Mujib was moved back to Mianwall. On Dec. 15, the day before the Pakistani surrender in the East, General Yahya Khan's plan for Sheikh Mujib, which he learned of the next morning, was set in motion.

Mianwali sits in the home district of Lieut. Gen. A. A. K. Niazi, who had replaced General Tikka Khan as commander in East Pakistan. On the 15th the prisoners, all of whom were from the district, were told that General Niazi had been killed by the Bengalis and that when their cell doors opened the next morning they were to kill Sheikh Mujib. They agreed enthusiastically, he said.

Mianwali sits in the home district of Lieut. Gen. A. A. K. Niazi, who had replaced General Tikka Khan as commander in East Pakistan. On the 15th the prisoners, all of whom were from the district, were told that General Niazi had been killed by the Bengalis and that when their cell doors opened the next morning they were to kill Sheikh Mujib. They agreed enthusiastically, he said.

At 4 A.M., two hours before the killing was to take place, Sheikh Mujib told me, the prison superintendent, who was friendly to him, opened his cell. “Are you taking me to hang me?” asked Sheikh Mujib, who had watched prison employees dig a grave outside his cell (they said it was a trench for his protection in the event of Indian air raids.) The superintendent, who was greatly excited, assured the prisoner that he was not taking him for hanging.

Sheikh Mujib was still dubious. “I told him, ‘If you're going to execute me, then please give me a few minutes to say my last prayers.’”

“No, there's no time!” said the superintendent, pulling at Mujib. “You must come with me quickly!”

As they slipped out of the prison the superintendent explained the plot. He took his prisoner to his own house about a mile away and kept him there for two days. The war was ending and there was considerable confusion in official circles, and on Dec. 18 the superintendent told Sheikh Mujib that word had leaked out about him and he had to move.

The official, who was also superintendent of police in the district, then took the Bengali leader to an unoccupied house several miles away. He was there nine days when soldiers asked the superintendent where he was. The superintendent replied he did not know. The officer in charge then told the superintendent that there was no reason to hide Sheikh Mujib or be frightened because Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the West Pakistani politician who had taken power from the discredited generals on Dec. 19, simply wanted to see Sheikh Mujib and talk with him.

Sheikh Mujib emerged and was immediately flown to Rawalpindi, where he was put under house arrest in the President's guest house.

After a few days, Mr. Bhutto, the leader of the majority party in the West, who had collaborated with the army in the moves that led to the crackdown in East Pakistan, went to see Sheikh Mujib, who said he greeted him: “Bhutto, what are you doing here?” Sheikh Mujib says he had learned of Mr. Bhutto's rise to power but was doing a little leg pulling.

“I am the President and also the chief martial‐law administrator,” was the reply, according to Sheikh Mujib. “A wonderful situation.”

Mr. Bhutto said, Sheikh Mujib recalled, that when General Yahya Khan was handing over power to him, he said that his one great regret was that he had not killed Sheikh Mujib and asked if he could “finish this one piece of work.” Mr. Bhutto told Sheikh Mujib that the general offered to predate the papers so it would appear that the execution took place under him. Mr. Bhutto refused.

Mr. Bhutto said, Sheikh Mujib recalled, that when General Yahya Khan was handing over power to him, he said that his one great regret was that he had not killed Sheikh Mujib and asked if he could “finish this one piece of work.” Mr. Bhutto told Sheikh Mujib that the general offered to predate the papers so it would appear that the execution took place under him. Mr. Bhutto refused.

Sheikh Mujib said today that the reason he refused was largely political. Mr. Bhutto reasoned, he said, that if the Bengali leader was executed, they would kill the nearly 100, 000 Pakistani soldiers who had surrendered in East Pakistan and then the people of the Punjab and the North‐West Frontier Province—where most of the West Pakistani troops came from—would blame Mr. Bhutto and rise against his Government.

Sheikh Mujib said that Mr. Bhutto kept pressing him to enter talks to retain some link, no matter how tenuous, between the two Pakistani regions.

“I told him I had to know one thing first—am I free or not?” Sheikh Mujib said. “If I'm free, let me go. If I'm not, I cannot talk.”

“You're free,” he quoted Mr. Bhutto as saying, “but I need a few days before I can let you go.”

Despite the promise of freedom, Sheikh Mujib said, he did not discuss substantive matters with Mr. Bhutto.

At another point, when Mr. Bhutto had said that the two wings were still united by law and tradition, Sheikh Mujib— reminding him that the Awami League won a national majority in the last election, the results of which were never honored — said: “Well, if Pakistan is still one country, then you are not President and chief martial‐law administrator. I am.”

On Jan. 7 the President went to see Sheikh Mujib for the third and last time. The Bengali leader said he told him: “You must free me tonight. There is no more room for delay. Either free me or kill me.”

Sheikh Mujib said Mr. Bhutto replied that it was difficult to make arrangements at such short notice, but finally agreed to fly him to London. Sheikh Mujib said that as Mr. Bhutto saw him off, he was still asking him to consider political ties with West Pakistan.

If you want to watch some videos on this topic, you can click on the links to YouTube videos below.

If you want to answer questions on this article to test how much you understand, you can click on the green box: Finished Reading?

Videos:

1. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Interview (2:55)

2. Sheik Mujibur Rahman Declares Region Independent, March 26, 1971 (3:03)

3. Sheikh Mujib's Returns to Bangladesh - January 10, 1972 (4:30)

4. Sheikh Mujibur Continues Talks (00:57)

5. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (1:15)

6. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Historic Interview after Independence from Pakistan (25:00)

7. Bangladesh: Mujib Returns (10:20)

8. Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman with David Frost (2:33)

9. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in London 8 January 1972 (2:56)

10. Interview of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (2:06)

He kissed his weeping wife and children good‐bye, telling them what they knew too well—that he might never return. Then the West Pakistani soldiers pushed him down the stairs, hitting him from behind with their rifles. He reached their jeep and then, in a reflex of habit and

He kissed his weeping wife and children good‐bye, telling them what they knew too well—that he might never return. Then the West Pakistani soldiers pushed him down the stairs, hitting him from behind with their rifles. He reached their jeep and then, in a reflex of habit and  Relaxed and with no

Relaxed and with no  The

The  Sheikh Mujib, who is a lawyer, knew he had no chance of

Sheikh Mujib, who is a lawyer, knew he had no chance of  Mianwali sits in the home district of Lieut. Gen. A. A. K. Niazi, who had replaced General Tikka Khan as commander in East Pakistan. On the 15th the prisoners, all of whom were from the district, were told that General Niazi had been killed by the Bengalis and that when their cell doors opened the next morning they were to kill Sheikh Mujib. They agreed

Mianwali sits in the home district of Lieut. Gen. A. A. K. Niazi, who had replaced General Tikka Khan as commander in East Pakistan. On the 15th the prisoners, all of whom were from the district, were told that General Niazi had been killed by the Bengalis and that when their cell doors opened the next morning they were to kill Sheikh Mujib. They agreed  Mr. Bhutto said, Sheikh Mujib

Mr. Bhutto said, Sheikh Mujib