Course description

The First Computers – Ancient & Modern

It may seem odd but the computer has, in fact, been invented twice. The first time was in mid-nineteenth century Britain and, then again, a hundred years later in the same country. The reasons are complicated but the original inventor, Charles Babbage, was both impatient and uninterested in communicating his work. Besides, the machine itself was not actually built until a few years ago, although the design pre-dated it by a century and a half.

It may seem odd but the computer has, in fact, been invented twice. The first time was in mid-nineteenth century Britain and, then again, a hundred years later in the same country. The reasons are complicated but the original inventor, Charles Babbage, was both impatient and uninterested in communicating his work. Besides, the machine itself was not actually built until a few years ago, although the design pre-dated it by a century and a half.

So, here are the stories of two eccentric and difficult men, Charles Babbage and Alan Turing, and an explanation of their roles in the invention of the computer.

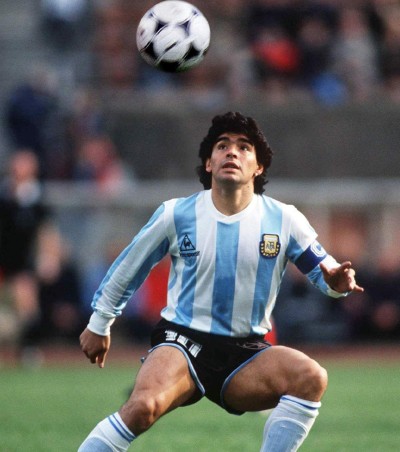

A century before British mathematician Alan Turing made the first all-purpose computer, Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace wrote about ‘the Analytical Engine’, a machine that had all the characteristics of the computers we use today but which was forgotten until the 1970s and only built in 2002. Of course, by that time we all lived in the world of Bill Gates’ Microsoft and Steve Jobs’ Apple, communicated by email and browsed the Internet. Why did nobody pay attention to Babbage’s and Lovelace’s work until so many years later? The answer lies in the personalities of the people who developed the idea.

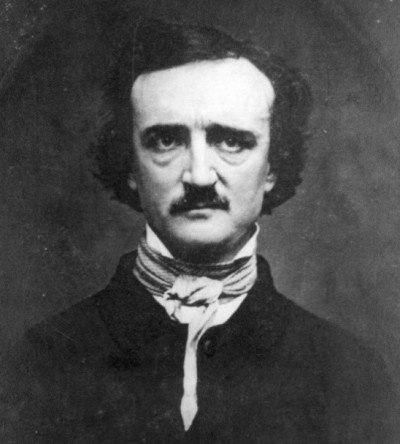

Charles Babbage was born in 1791 and was a mathematician well-known not only for his theories but also for his practical designs to build machines. He was Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge, a job that Isaac Newton had before him. The British government gave Babbage enough money to build the first computer; called ‘The Difference Machine’, in the 1830s, which was powered by steam but which started to bore him and so he never made it. That was because he already had an idea to make a more surprising and revolutionary machine that did not just calculate numbers, but could analyse information.

Charles Babbage was born in 1791 and was a mathematician well-known not only for his theories but also for his practical designs to build machines. He was Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge, a job that Isaac Newton had before him. The British government gave Babbage enough money to build the first computer; called ‘The Difference Machine’, in the 1830s, which was powered by steam but which started to bore him and so he never made it. That was because he already had an idea to make a more surprising and revolutionary machine that did not just calculate numbers, but could analyse information.

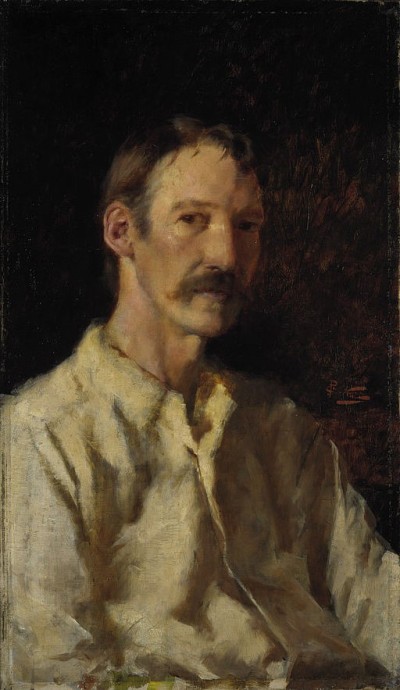

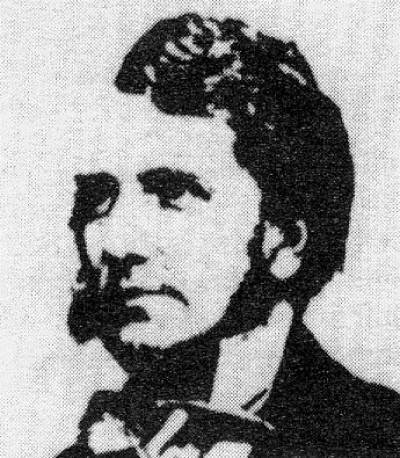

Ada Lovelace was the daughter of Lord Byron, an extraordinary aristocrat who wrote poetry, fought for the poor and oppressed, and lived a life that shocked everyone around him. He married Anne Isabella Millbanke but left her only weeks after Ada was born in 1815. Ada’s mother brought her up never to trust men and made sure that she got an excellent education, especially in maths and science. Because Ada was often ill in her childhood – she could not walk for three years after an illness when she was twelve, for instance – she had a lot of time to study. Ada’s relationship with her mother was not close either. It seems she was afraid of her.

Ada Lovelace was the daughter of Lord Byron, an extraordinary aristocrat who wrote poetry, fought for the poor and oppressed, and lived a life that shocked everyone around him. He married Anne Isabella Millbanke but left her only weeks after Ada was born in 1815. Ada’s mother brought her up never to trust men and made sure that she got an excellent education, especially in maths and science. Because Ada was often ill in her childhood – she could not walk for three years after an illness when she was twelve, for instance – she had a lot of time to study. Ada’s relationship with her mother was not close either. It seems she was afraid of her.

In 1832, Ada and her mother went to one of Babbage’s social evenings at his house. There she heard about his calculating machine and later wrote to him to ask to see the blueprints of the design. Of course, it was unusual for a girl to make friends with one of the most famous scientists of the age, but Babbage helped the teenager to develop her mathematics and took her to see industrial machines in different parts of England. When she married and had children, he continued his friendship with her and helped to improve her scientific education – a very unusual thing for a married woman to do at that time. (Ada was not a normal housewife: she did not like her three children, drank too much, gambled and probably had affairs with other men than her husband.)

But if Babbage was useful to Ada, she was just as important to him. He made many enemies in the scientific world and among the politicians who paid for his work. Often Babbage shouted at them in public and never knew when to shut up. He fought battles with them that he had no chance of winning. What’s more, he was not interested in writing about his research. This made it difficult for him to get the money he needed to continue his scientific work.

But if Babbage was useful to Ada, she was just as important to him. He made many enemies in the scientific world and among the politicians who paid for his work. Often Babbage shouted at them in public and never knew when to shut up. He fought battles with them that he had no chance of winning. What’s more, he was not interested in writing about his research. This made it difficult for him to get the money he needed to continue his scientific work.

In the end, Babbage left England to give talks about his work in Italy. He hoped that the Italian government would give him the money he needed to build his Analytical Engine and this would make the British take him seriously. But he would not publish his work and, so, an Italian mathematician, Luigi Menabrea (who later became the Prime Minister of his country), made notes at Babbage’s talks and published these in Switzerland.

Ada took these notes about the Analytical Engine and added her own thoughts. Although she was not a great mathematician, she had the ability to see the machine was the first form of artificial intelligence and the uses it might have. She probably understood this better than Babbage, the machine’s inventor. Scholars still argue about how much Babbage helped her with her notes on the Analytical Engine, but one thing is certain: Babbage and Ada were good friends and made a great scientific team. And, together, they had the idea for and made the design of the first machine that could use symbols to play with data, just like computers do today.

Ada died in 1852 of cancer of the uterus. In her last weeks, her behavior was very changeable. Her doctors were probably giving her pain killers with opium (from which we get heroin today) and she was certainly drinking heavily. We can never know what she whispered to her husband from her sickbed, but he left her and did not return to their house until she was dead. One of the last things she did was to ask Babbage to look after her fortune when she was dead.

Ada died in 1852 of cancer of the uterus. In her last weeks, her behavior was very changeable. Her doctors were probably giving her pain killers with opium (from which we get heroin today) and she was certainly drinking heavily. We can never know what she whispered to her husband from her sickbed, but he left her and did not return to their house until she was dead. One of the last things she did was to ask Babbage to look after her fortune when she was dead.

Ada’s published notes were forgotten until the 1970s and Babbage’s machine not built until 2002. It works but weighs five tons. If Ada had lived, we might have had the computer a long time before Alan Turing made his first machine after the Second World War.

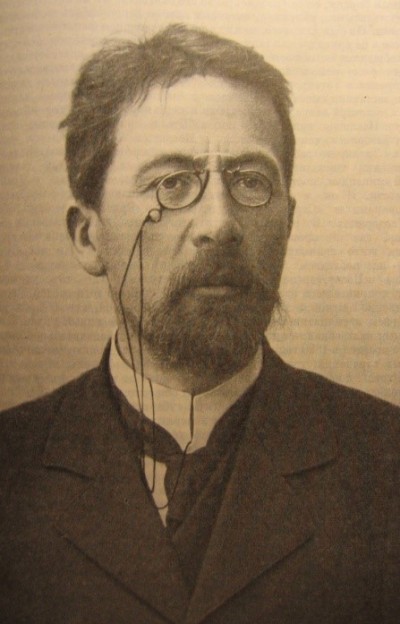

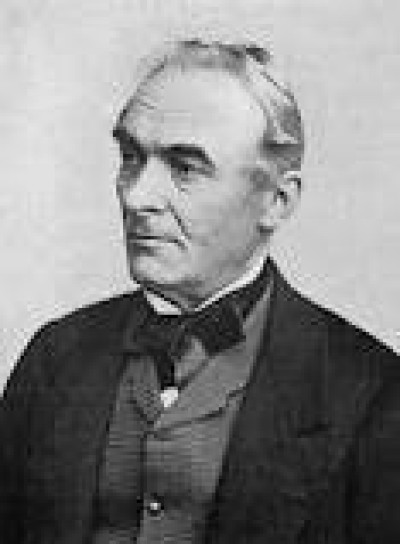

Of course, many people do not know who Alan Turing was, despite names such as Steve Jobs and Bill Gates becoming legends even within their own lifetimes. Turing’s name is not well-known, although he was one of the most brilliant scientists the United Kingdom produced in the twentieth century. The reason for this is that Turing was gay at a time when it was against the law in Britain. So, the secrecy of his work made him a ‘security risk’. If Communist Russia blackmailed him, he could tell them British secrets.

But let’s look at what Turing did for his country.

During the Second World War, Turing worked at a secret British location, called Bletchley Park, on breaking codes used by Nazi Germany. He produced a machine that could understand the German code, Enigma. This meant that the British knew what the Germans were going to do before they did it. Practically, it meant that the British knew where German submarines were in the Atlantic Ocean and, so, could destroy or stay away from them. Food, guns and soldiers could now more easily arrive from the USA in Britain. Some university academics believe that breaking the Enigma code shortened the War by two years and saved fourteen million lives.

During the Second World War, Turing worked at a secret British location, called Bletchley Park, on breaking codes used by Nazi Germany. He produced a machine that could understand the German code, Enigma. This meant that the British knew what the Germans were going to do before they did it. Practically, it meant that the British knew where German submarines were in the Atlantic Ocean and, so, could destroy or stay away from them. Food, guns and soldiers could now more easily arrive from the USA in Britain. Some university academics believe that breaking the Enigma code shortened the War by two years and saved fourteen million lives.

After the Second World War ended in 1945, Turing invented something called the Turing Machine. It was a basic, general use computer (although it was big enough to fill a room – not like our laptops today!) He was also very interested in AI or Artificial Intelligence. Turing’s interests in mathematics, computer theory and also in making machines mean that he is sometimes called the Father of Computing.

Asa Briggs, a famous British historian but also a code breaker at Bletchley Park during the Second World War, said this about Turing:

"You needed exceptional talent, you needed genius at Bletchley and Turing was that genius."

But with genius there is sometimes strange behavior and many of his friends at Bletchley Park remember that the ‘Professor’, as they called him, locked his coffee cup to a chain so that nobody could steal it. He also attended many meetings in London seventy kilometers from Bletchley Park but, sometimes, decided to run there instead of taking the train or driving.

But with genius there is sometimes strange behavior and many of his friends at Bletchley Park remember that the ‘Professor’, as they called him, locked his coffee cup to a chain so that nobody could steal it. He also attended many meetings in London seventy kilometers from Bletchley Park but, sometimes, decided to run there instead of taking the train or driving.

However, coffee cups and running did not worry the government. What worried them was that he slept with a nineteen-year-old man.

One day Turing noticed that there were some things missing from his house. His new friend told him that he knew the thief. Turing stupidly rang the police and then, even more stupidly, told them that his lover knew the thief. The police arrested Turing – not the thief. The court did not send Turing to prison but he had to have injections to stop him feeling sexy. These injections also caused him to grow breasts.

In 1954, his cleaning lady found Turing dead in his bedroom. The police said it was suicide, but his mother and many friends believe it was an accident. Others think the government assassinated him because he knew too many British secrets and was a security risk.

But we can be sure of one thing: Britain lost one of its greatest scientific brains of the century, perhaps of all time.

If you want to watch some videos on this topic, you can click on the links to YouTube videos below.

If you want to answer questions on this article to test how much you understand, you can click on the green box: Finished Reading?

Videos :

1. Charles Babbage Biography | Father of Computer (3:40)

2. History and Generation of Computers (5:09)

3. Charles Babbage and his Difference Engine (5:47)

4. Alan Turing –Celebrating the Life of a Genius (8:13)

5. Who was Ada Lovelace, The World’s First Computer Nerd? (4:25)

6. Bill Gates Co-Founder of Microsoft (1955-) (4:30)

7. Babbage’s Analytical Engine- Computer Pile (13:25)

8. Flaw in the Enigma Code- Number Pile (10:58)

9. Turing Machines (4:20)

10. Lord Asa Briggs on his Book ‘Secret Days-Code- Breaking at Bletchley Park’ (8:29)

It may seem

It may seem  Charles Babbage was born in 1791 and was a mathematician well-known not only for his theories but also for his practical designs to build machines. He was Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge, a job that Isaac Newton had before him. The British government gave Babbage enough money to build the first computer; called ‘The Difference Machine’, in the 1830s, which was

Charles Babbage was born in 1791 and was a mathematician well-known not only for his theories but also for his practical designs to build machines. He was Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge, a job that Isaac Newton had before him. The British government gave Babbage enough money to build the first computer; called ‘The Difference Machine’, in the 1830s, which was  Ada Lovelace was the daughter of Lord Byron, an extraordinary

Ada Lovelace was the daughter of Lord Byron, an extraordinary  But if Babbage was useful to Ada, she was just as important to him. He made many enemies in the scientific world and among the politicians who paid for his work. Often Babbage shouted at them in public and never knew when to shut up. He fought battles with them that he had no chance of winning. What’s more, he was not interested in writing about his research. This made it difficult for him to get the money he needed to continue his scientific work.

But if Babbage was useful to Ada, she was just as important to him. He made many enemies in the scientific world and among the politicians who paid for his work. Often Babbage shouted at them in public and never knew when to shut up. He fought battles with them that he had no chance of winning. What’s more, he was not interested in writing about his research. This made it difficult for him to get the money he needed to continue his scientific work. Ada died in 1852 of cancer of the uterus. In her last weeks, her behavior was very changeable. Her doctors were probably giving her pain killers with opium (from which we get heroin today) and she was certainly drinking heavily. We can never know what she

Ada died in 1852 of cancer of the uterus. In her last weeks, her behavior was very changeable. Her doctors were probably giving her pain killers with opium (from which we get heroin today) and she was certainly drinking heavily. We can never know what she  During the Second World War, Turing worked at a secret British

During the Second World War, Turing worked at a secret British But with

But with