Course description

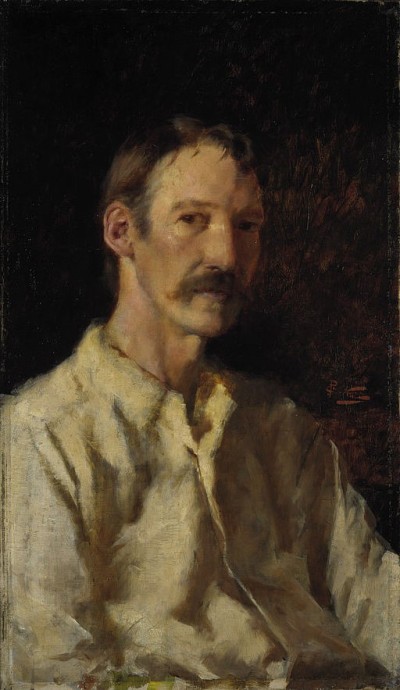

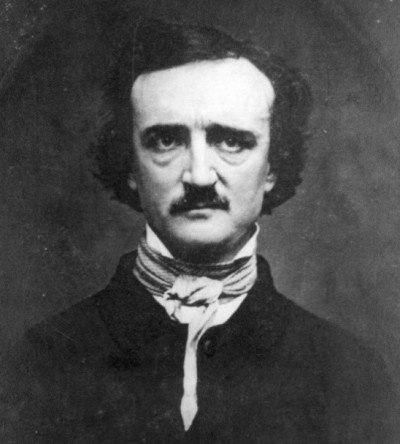

Charles Dickens was born in 1812 and spent much of his early life living in great hardship. His father was sent to prison because he owed money and young Dickens had to do a job he hated to support his family. Even when his father got out of prison, he was not allowed to leave the job – something he never forgave his mother for. He later worked as an office boy and a journalist before he began writing novels.

His work was immediately popular and has never gone out of print in the UK and USA, (which Dickens visited twice). His writing has dramatic plots, with some of the most life-like characters in literature, either because they are so evil (such as Bill Sykes in ‘Oliver Twist’ and Mr. Squeers in ‘Nicholas Nickleby’) or eccentric (for instance, Mr. Micawber in ‘David Copperfield’ and Miss Havisham in ‘Great Expectations’). Yet, his novels also include serious social messages.

It may interest you, as you are reading this story, to know that Dickens was in a very serious train accident himself, in which many passengers died and that certainly affected him greatly for the rest of his life.

He died of a stroke as a result of overwork in 1870.

The Signal Man

"Hello! Below there!"

When he heard the voice calling to him, he was standing at the door of his signal box, with a flag in his hand. Considering his surroundings, he should have known where the voice came from; but instead of looking up to where I stood on the top of the steep hill, he turned around and looked down the railway line. There was something remarkable in his way of doing so, though I cannot say why. But it was strange enough for me to notice, even in a sunset so angry that I had to cover my eyes with my hand before I saw him at all.

"Hello! Below!"

From looking down the line, he turned around again and, raising his eyes, saw me high above him.

"Is there a path I can use to come down and speak to you?"

He looked up at me without replying, and I looked down at him without repeating my question too soon. Just then there came a vibration in the earth and air, quickly changing into a violent shaking. When the steam from this train had passed, I looked down again, and saw him putting away the flag he had waved while the train went by.

asked my question again. After a pause, when he seemed to look at me with fixed attention, he pointed with his flag towards a place two or three hundred metres away. I called down to him, "All right!" and headed for that point. There I found a rough zigzag path, which I followed.

The path was unusually steep. It was made of stone, which became wetter as I went down. For these reasons, I had time to remember the reluctance with which the man had shown me the path before I met him.

When I came down low enough on the zigzag path to see him again, he was waiting for me to appear. He had his left hand at his chin, and his left elbow rested on his right hand over his chest. He was so watchful that I stopped a moment, wondering why.

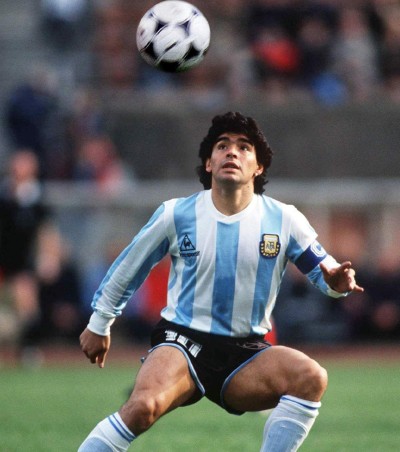

I continued on my way down, and stepping out on the railway line, saw that he was a dark man, with a beard and rather heavy eyebrows. His post was in as lonely and dismal a place as I had ever seen. On both sides, there was a wet wall of stone, so that only a strip of sky could be seen. It ended in both directions in a gloomy red light and the gloomier entrance to a black tunnel. So little sunlight ever found its way to this place that it had a smell like death; and so much cold wind rushed through it that I felt like I had left the natural world.

Before he moved, I was near enough to him to touch him. Even then he did not turn his eyes away from mine, but stepped back and lifted his hand.

This was a lonely place to live (I said). Visitors were rare, I supposed, but not unwelcome, I hoped? I think he only saw me as a man who had lived in narrow limits all his life. I spoke to him, but I am unsure of the words I used because there was something in the man that made me afraid.

He looked curiously towards the red light near the tunnel, as if something were missing, and then looked at me. That light was part of his job, wasn’t it?

He answered in a low voice, "Don't you know it is?"

The terrible thought came into my mind, as I watched the fixed eyes, that this was a spirit, not a man. I have wondered since then, whether he was mad.

I stepped back. But as I moved, I detected fear of me in his eyes and this made me think that he was, after all, a man, not a spirit.

"You look at me," I said, forcing a smile, "as if you’re afraid of me."

"I wondered," he replied, "whether I’d seen you before."

"Where?"

He pointed to the red light he had looked at.

"There?" I said.

Watching me carefully, he replied (but without a sound), "Yes."

“What should I be doing there? However, it doesn’t matter. I was never there, you can be sure."

"I think I can," he answered. "Yes, I’m sure I can."

His behaviour now became normal, like my own. He replied to my remarks readily, and in well-chosen words. Did he have much work to do there? Yes, he had enough responsibility but exactness and watchfulness were required, but he had almost no actual work. To change that signal, to prepare those lights and to turn this iron handle now and then, was all he had to do. About those many long and lonely hours, he could only say that the routine of his life had changed and he had grown used to it. He had taught himself a language down here – if a language studied from books with no idea of its pronunciation could be called learning it. He had also worked at fractions and decimals, and tried a little algebra, but he had always had a poor head for numbers. Did he always have to stay in the damp air when he was on duty? Couldn’t he ever go up into the sunshine on the hills? That depended on the circumstances. Under some conditions there would be less to do on the line, and the same was true of certain hours of the day and night. In bright weather, he chose to walk up into the sunshine sometimes, but his electric bell could ring at any time and listening for it meant that walking up the hill was less relaxing than I supposed.

He took me into his box, where there was a fire, a desk for an official book in which he had to write certain notes and the little bell he had spoken about. I hoped that he would excuse the remark that he had been well educated, perhaps educated above his job. But he said that there were many people like him, that he’d heard it was so in the police force, even in the army, and that he knew it was so, more or less, with railway staff. When he was young (if I could believe it, sitting in that hut), he had been a student of philosophy and attended lectures, but he’d been wild, misused his opportunities and never come up again. He had no complaints. It was far too late to change his future.

All that I have recorded here he said in a quiet way, with his dark looks divided between me and the fire. He threw in the word, "Sir," from time to time, and especially when he talked about his youth, as if to make me understand that he pretended to be nothing more than I found him. He was interrupted several times by the little bell and had to read off messages and send replies. Once he had to stand outside the door as a train passed and speak to the driver. I noticed he was exact and careful, breaking off his conversation and remaining silent until what he had to do was done.

In a word, I thought this man must be one of the safest employees in that job, except when he twice turned pale, turned his face towards the little bell when it did NOT ring, opened the door of the hut (which was kept shut to keep out the damp), and looked out towards the red light near the tunnel. On both those occasions, he came back to the fire with that strange look on him which I had noticed, without being able to define.

I said, when I got up to leave him, "You almost make me think that I’ve met a satisfied man."

(I’m afraid I said it to get him to talk.)

"I believe I used to be so," he answered, in the low voice in which he had first spoken; "but I’m troubled, sir, I am troubled."

He would have taken the words back if he could. He had said them, however, and I quickly asked, "With what? What’s your trouble?"

"It’s very difficult to share, sir. It’s very, very difficult to speak about. But, if you ever visit me again, I’ll try to tell you."

"I certainly plan to visit again. Say, when is convenient?"

"I go off early in the morning and I’ll be on again at ten tomorrow night, sir."

"I’ll come at eleven."

He thanked me and showed me out. "I'll show my white light, sir," he said, in his low voice, "till you’ve found the way up. When you’ve found it, don't call out! And when you are at the top, don't call out!"His manner seemed to me to make the place colder, but I said no more than, "Alright."

"And when you come down tomorrow night, don't call out! Let me ask you a final question. What made you shout, 'Hello! Below there!' tonight?"

"I have no idea," said I. "I said something like that."

"Not ‘like that’, sir. Those were the exact words. I know them well."

"I said them, no doubt, because I saw you below."

"For no other reason?"

"What other reason could I have?"

"You had no feeling that they came to you in any supernatural way?"

"No."

He wished me good night, and held up his light. I walked by the side of the railway line (with a very unpleasant feeling of a train coming behind me) until I found the path. It was easier to walk up than down and I got back to my hotel without any mishap.

At exactly the time I had arranged for my appointment the following night, I started walking along the path. He was waiting for me at the bottom, with his white light on. "I haven’t called out," I said, when we came close together. "May I speak now?" "By all means, sir." "Good evening, then, and here's my hand." "Good evening, sir, and here's mine." With that we walked side by side to his box, entered it, closed the door, and sat down by the fire.

"I have made up my mind, sir," he began, as soon as we were seated, and speaking only a little above a whisper, "that you won’t have to ask me twice what troubles me. I mistook you for someone else yesterday evening. That worries me."

"That mistake?"

"No. That someone else."

"Who is it?"

"I don't know."

"Like me?"

"I don't know. I never saw the face. The left arm is across the face and the right arm is waved, violently waved. This way."

I followed his action with my eyes, and it was the action of an arm waving, "Clear the way!"

"One moonlit night," said the man, "I was sitting here when I heard a voice cry, 'Hello! Below there!' I started up, looked out that door, and saw this someone else standing by the red light near the tunnel, waving as I just now showed you. The voice seemed hoarse with shouting, and it cried, 'Look out! Look out!' And then, 'Hello! Below there! Look out!' I took my lamp, turned it on red, and ran towards the figure, calling, 'What's wrong? What’s happened? Where?' It stood just outside the blackness of the tunnel. I went so close to it that I wondered why it kept its arm across its eyes. I ran right up to it and had my hand out to pull the arm away, when it disappeared."

"Into the tunnel?" I said.

"No. I ran into the tunnel, five hundred metres. I stopped and held my lamp above my head. I ran out again faster than I had run in (because I hated the tunnel), and I looked all round. I ran back here and telegraphed both ways, 'An alarm has been given. Is anything wrong?' The answer came back, both ways, 'All is well.'"

I explained how this figure must have been a hallucination. "As to an imaginary cry," I said, "only listen for a moment to the wind in this unnatural valley while we speak so low, and to the wild sound it makes on the telegraph wires."

That was all very well, he replied, after we had sat listening for a while, and he ought to know something of the wind and the wires, -- he who so often passed long winter nights there, alone and watching. But he said that he had not finished.

I apologised, and he slowly added these words, touching my arm:

"Six hours after the appearance of the figure, a tragic accident on this line happened and within ten hours the dead and wounded were brought along through the tunnel over the spot where the figure had stood."

It was true, I answered, that this was a remarkable coincidence, which would, of course disturb him. But it was unquestionable that coincidences continually happened and they must be considered.

He again said that he had not finished.

"This," he said, again laying his hand on my arm, and glancing over his shoulder with hollow eyes, "was just a year ago. Six or seven months passed and I’d recovered from the shock, when one morning, as day was breaking, I was standing at the door and looking towards the red light, and saw the figure again." He stopped, with a fixed look at me.

"Did it make any sound?"

"No. It was silent."

"Did it wave its arm?"

"No. It stood with both hands in front of its face. Like this."

Once more I followed his action with my eyes. It was one of mourning.

"Did you go up to it?"

"I came in and sat down because it made me faint. When I went to the door again, it was daylight and the ghost was gone."

"But nothing followed? Nothing came of this?"

"That very day, as a train came out of the tunnel, I noticed what looked like a confusion of hands and heads, and something waved. I saw it just in time to signal the driver, Stop! He put his brake on, but the train moved a hundred and fifty yards or more past here. I ran after it and, as I went along, I heard terrible screams and cries. A beautiful young lady had died and was brought in here and laid down on this floor between us."

I pushed my chair back instinctively, as I looked from the floor to the signal man."True, sir. True. I’m telling you precisely as it happened."

I could think of nothing to say and my mouth was very dry.

He started up again. "Now, sir, listen to this and see how my mind is troubled. The ghost came back a week ago. Ever since, it’s been there, now and again."

"At the light?"

"At the danger light."

"What does it seem to do?"

He repeated that former wave of, "Clear the way!"

Then he went on. "I have no peace or rest because of it. It calls to me, for many minutes together, in a painful way, 'Below there! Look out! Look out!' It stands waving to me. It rings my little bell."

"Did it ring your bell yesterday evening when I was here and you went to the door?"

"Twice."

"See," I said, "how your imagination confuses you. My eyes were on the bell, and my ears were open and it did NOT ring at those times. No, only when it was rung by the station communicating with you."

He shook his head. "I’ve never made a mistake like that yet, sir. I’ve never confused the ghost's ring with the man's. The ghost's ring is a strange vibration in the bell. I am not surprised you failed to hear it. But I heard it."

"And did the ghost seem to be there, when you looked out?"

"It WAS there."'

"Both times?"

He repeated firmly: "Both times."

"Will you come to the door with me and look for it now?"

He bit his lip but got up. I opened the door and stood on the step, while he stood in the doorway. There was the danger light. There was the tunnel. There were the high stone walls. There were the stars.

"Do you see it?" I asked him, carefully examining his face.

"No," he answered. "It’s not there."

"Agreed," I said.

We went in, shut the door and sat down again. I was thinking how I might take advantage of his not seeing any ghost, when he started the conversation in such a matter-of-fact way.

"By this time you’ll fully understand, sir," he said, "that what troubles me is what the ghost means."

I was not sure, I told him, that I did fully understand."What is it warning against?" he said, considering, with his eyes on the fire and only at times turning them on me. "What is the danger? Where is it? There is danger somewhere on the line. Some disaster will happen. It cannot be doubted after what’s happened. But what can I do?"

He pulled out his handkerchief, and wiped his forehead.

"If I telegraph ‘Danger’, on either side of me, or on both, I can give no reason for it," he went on, wiping his hands. "I should get into trouble, and do no good. They’d think I was mad. This is the way it would work: Message: 'Danger! Take care!' Answer: 'What Danger? Where?' Message: 'Don't know. But, take care!' They would dismiss me. What else could they do?"

His unhappiness was sad to see. It was the mental torture of a conscientious man, oppressed by a responsibility for others’ lives.

"When it first stood under the danger light," he went on, pushing his dark hair back from his head, "why didn’t it tell me where that accident was going to happen, if it must happen? Why not tell me how it could be avoided, if it could have been avoided? When it came the second time and hid its face, why not tell me, instead, 'She is going to die. Let them keep her at home'? If it came, on those two occasions, only to show me that its warnings were true and so to prepare me for the third, why not warn me clearly now? And me! A poor signal-man in this lonely station! Why not go to somebody who might be believed and had power to act?"

When I saw him in this state, I knew that for the poor man's sake, as well as for public safety, I had to get him to relax. Therefore, I told him that whoever did his duty must do well and that at least it was his comfort that he understood his duty, though he did not understand these ghostly appearances. I succeeded far better in this than in my attempt to persuade him that he was wrong. He became calm; his chores increased as it got later and I left him at two in the morning. I offered to stay the night, but he would not hear of it.

More than once I looked back at the red light as I walked up the pathway. I did not like the light and I’d have slept poorly if my bed had been under it. Nor did I like the two accidents and the dead girl. I see no reason to hide that.But what I thought about most was what I ought to do, now that I had heard the signal man’s secret? The man was intelligent, careful and exact; but how would this last in his state of mind? He held a most important post, and would I (for instance) like to risk my own life on the chances of his continuing to do his job properly?

But there would be something treacherous in communicating what he had told me to his employers, without first speaking plainly to him and offering to go with him to the best doctor we could find to get his opinion. The next night, there would be a change in his shift, he’d told me, and he would be off an hour or two after sunrise, and on again soon after sunset. I had agreed to return then.

The next evening was lovely and I walked out early to enjoy it. The sun was not quite down when I walked up the path. I’d walk for another hour, I said to myself, and it would then be time to go to my signal-man's box.

Before continuing, I mechanically looked down, from the point where I had first seen him. I cannot describe the fear I felt when, at the tunnel, I saw a figure, with his left arm across his eyes, waving his right arm.

The nameless horror passed in a moment, because I saw that it was actually a man, and that there was a little group of other men, standing a short distance away, he was showing the gesture to. The danger light was not yet lit.

With a sense that something was wrong, blaming myself that something terrible had come after leaving the man there, without sending anyone to look after him, I went down the path as fast as I could.

"What’s the matter?" I asked the men.

"The signalman was killed this morning, sir."

"Not the man belonging to that box?"

"Yes, sir."

"Not the man I know?"

"You’ll recognise him, sir, if you knew him," said the man who spoke for the others, uncovering his own head, and raising the sheet that covered him, "because his face is quite calm."

"Oh, how did this happen, how did this happen?" I asked, turning from one to another.

"He was cut down by an engine, sir. Nobody in England knew his work better. But somehow he was on the rail. It was at sunrise. He’d turned off the light and had the lamp in his hand. As the engine came out of the tunnel, his back was towards it and it cut him down. That man drove it and was showing how it happened. Show the gentleman, Tom."

The man, who wore a dark jacket, stepped back to his place at the tunnel.

"Coming into the tunnel, sir," he said, "I saw him at the end. There was no time to slow down and I knew he was very careful. As he didn't seem to pay attention, I called to him as loudly as I could."

"What did you say?"

"I said, 'Below there! Look out! Look out! Clear the way!'"I started.

"Ah! It was a dreadful time, sir. I never stopped calling to him. I put this arm in front of my eyes not to see, and I waved this arm to the last moment, but it was no use."