Course description

Taxonomy – the Science of Classification

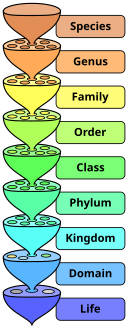

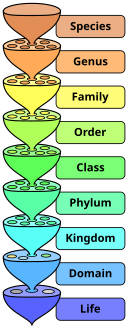

Aristotle as long ago as 350 B.C. began classifying living organisms on the Greek island of Lesbos. This work has continued uninterrupted ever since. The best-known taxonomist was the Swede, Carl Linnaeus, who lived in the eighteenth century and who organized the classification of all living organisms into flora (plants) and fauna (animals). He also introduced a hierarchical system with class at the top of the pyramid, then order, followed by genus, and, finally, species. As such, the Bengal Tiger would be classified as followed:

Aristotle as long ago as 350 B.C. began classifying living organisms on the Greek island of Lesbos. This work has continued uninterrupted ever since. The best-known taxonomist was the Swede, Carl Linnaeus, who lived in the eighteenth century and who organized the classification of all living organisms into flora (plants) and fauna (animals). He also introduced a hierarchical system with class at the top of the pyramid, then order, followed by genus, and, finally, species. As such, the Bengal Tiger would be classified as followed:

Kingdom: Animal

Class: Mammal

Order: Carnivore

Genus: Tiger

Species: Bengal Tiger

However, scientists have continually refined this system by trying to state what characteristics each level in the hierarchy should have. For instance, plants photosynthesise to get food. For this, they need sunlight, water, carbon dioxide and chlorophyll. There are other traits too. Plants cannot move, for example, as they have roots. Yet, we can all think of many exceptions to these rules: sunflowers move so that their flowers face the sun; moss does not like sunlight or have roots; many plants are not, in fact, green, as they do not have chlorophyll. We could continue, of course, with a much longer list of exceptions. In fact, some organisms which Linnaeus believed were plants are no longer seen as plants at all, like lichen.

In this lecture, we will look at typical plants that conform to the general rules of what makes a plant a plant, but we will also study an exception or two to illustrate the difficulty of classification. Along the way, we will consider the history of human relationships with these plants and their social significance in our lives.

The Strange Biology of Meat-Eating Plants

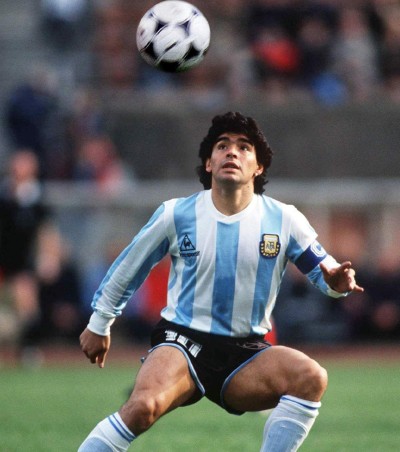

In 1951, John Wyndham published his successful novel, ‘The Day of the Triffids’, which was also recorded for the radio, made into a Hollywood film and adapted several times for television series. The novel is about a plant, called a triffid, which attacks and eats people. It’s highly poisonous, grows very tall and can move fast. It also reproduces quickly and so, in Wyndham’s book, there were hundreds of thousands of them all over the world.

In 1951, John Wyndham published his successful novel, ‘The Day of the Triffids’, which was also recorded for the radio, made into a Hollywood film and adapted several times for television series. The novel is about a plant, called a triffid, which attacks and eats people. It’s highly poisonous, grows very tall and can move fast. It also reproduces quickly and so, in Wyndham’s book, there were hundreds of thousands of them all over the world.

The plants seemed evil because they realised where people were living and waited for them to leave their homes. Then they attacked. ‘The Day of the Triffids’ was a bestseller and, in fact, it is still in print today. People love being afraid and man-eating plants that attack by surprise are a frightening idea!

We don’t know whether John Wyndham used the real meat-eating plant, the Venus flytrap, as a model for his triffid. Originally, it comes from a very small area – within a sixty-mile radius of Wilmington, North Carolina, in the United States, although there is also a colony near Washington nowadays.

The Venus flytrap catches insects and spiders, which are its main food, with a trap on its leaves. When its prey crawl along the leaves and touch a hair, the trap closes – but only if they touch a different hair in the next twenty seconds. This second-touch mechanism is a useful safeguard for the plant against wasting energy and means it can differentiate between its dinner and, for instance, falling rain. But if the insect comes into contact with a second hair within twenty seconds, the trap will shut with lightning speed. It takes only about one-tenth of a second.

The edges of the leaves are covered with hairs, which close to prevent large prey from escaping. But the gaps between the hairs also allow small insects to get away, perhaps because digesting them would take more energy than the plant would get from the small bodies. If large prey moves inside the trap, the hairs close more tightly and digestion starts faster. The closed leaves become a kind of stomach where acids kill and start to digest the insect. This lasts about ten days and when the leaves open again, there is almost nothing left. The plant is then ready to catch more prey. If, on the other hand, the insect is so small that it can escape through the hairs, the leaves re-open in twelve hours.

The edges of the leaves are covered with hairs, which close to prevent large prey from escaping. But the gaps between the hairs also allow small insects to get away, perhaps because digesting them would take more energy than the plant would get from the small bodies. If large prey moves inside the trap, the hairs close more tightly and digestion starts faster. The closed leaves become a kind of stomach where acids kill and start to digest the insect. This lasts about ten days and when the leaves open again, there is almost nothing left. The plant is then ready to catch more prey. If, on the other hand, the insect is so small that it can escape through the hairs, the leaves re-open in twelve hours.

You probably think that the Venus flytrap must be a big plant with many strong branches, but it is actually quite small. The tallest is only three to ten centimetres. It also takes the plant as long as five years to reach its full size. But it can live for 20 to 30 years.

The most interesting question, of course, is why this plant evolved in the way it did. Most carnivorous plants choose their prey very carefully, according to the kind of trap they have. With the Venus flytrap, prey is limited to beetles, spiders and other crawling insects. They probably came from another, earlier family of meat-eating plants, called Drosera, which use a sticky trap, instead of one that suddenly closes. We can’t be sure about the Venus flytrap’s family tree though, because most fossils are from larger plants which have wood in them. The flytrap doesn’t.

Anyway, while Drosera catch smaller, flying insects, flytraps are only interested in larger, crawling ones, which usually walk over the plants instead of flying to them. Of course, larger insects are more likely to get free from sticky surfaces too.

Anyway, while Drosera catch smaller, flying insects, flytraps are only interested in larger, crawling ones, which usually walk over the plants instead of flying to them. Of course, larger insects are more likely to get free from sticky surfaces too.

Carnivorous plants are found in areas where the soil is poor. Their carnivorous traps evolved to allow them to get the important food they could not take from the sandy, wet earth where they grew. According to research done in 1992, there are only 35,800 plants in their natural habitat. This suggests the plants might become extinct in the wild. Perhaps because of their unusually violent means of getting their daily diet, Venus flytraps are popular plants in people’s houses and gardens. In fact, there are about five million of them outside their natural habitat, even though it is not easy to grow them because they need conditions very similar to those in the wild.

Home cultivation may, therefore, be the answer to worries about the plants becoming extinct. But it’s worth remembering that John Wyndham’s triffids also became a threat when they were grown for their valuable oils. It was only when farmers began to cultivate them on a large scale that they fought back!

The Bamboo - Myths, Uses and a Plague of Rats

Bamboo plays a major part in many East Asian cultures, although it also grows in Africa, the United States, South America and Australia.

There are many myths around the importance that bamboo played in the creation of humankind. For instance, in the Andaman Islands, people believe humanity came from a bamboo stem. In the Philippines, mythology tells the story of the first man, called Malakás (‘Strong’), and the first woman, Maganda (‘Beautiful’), who each came out of one half of a broken bamboo stem on an island formed after a battle between Sky and Ocean.

There are many myths around the importance that bamboo played in the creation of humankind. For instance, in the Andaman Islands, people believe humanity came from a bamboo stem. In the Philippines, mythology tells the story of the first man, called Malakás (‘Strong’), and the first woman, Maganda (‘Beautiful’), who each came out of one half of a broken bamboo stem on an island formed after a battle between Sky and Ocean.

Bamboo is an important part of the culture of Vietnam too. It is a symbol of the country and the Vietnamese soul: open, hard-working, flexible and optimistic.

However, it is in China where bamboo has become an essential part of everyday life and thinking. There, the bamboo, plum blossom, orchid and chrysanthemum are called the Four Gentlemen. Bamboo, one of the ‘four gentlemen’, is seen as a role model for young men because it has the characteristics of perseverance and honesty, as well as simplicity and elegance.

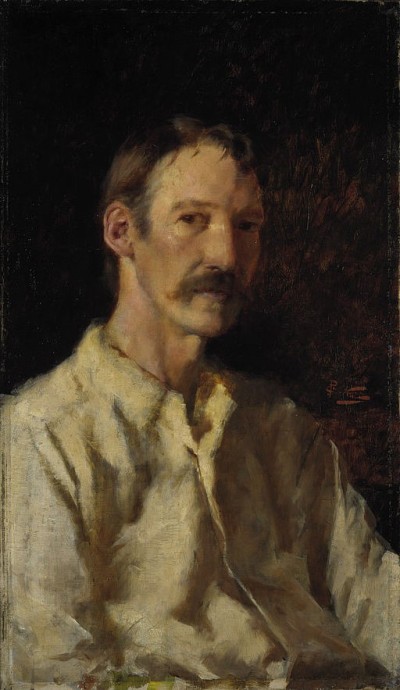

Ancient Chinese poets wrote about bamboo to say what a true gentleman should be like. BaiJuyi, who lived from 772 to 846, for example, thought a man did not need to be physically strong, but he must stick to his aims, never giving up what he believed in. He should also be open to new ideas and feelings, just like the bamboo is hollow inside, so his heart should not be too proud to accept everything good.

Bamboo is not only the symbol of a gentleman, but also has an important role in Buddhism. In the first century, this philosophy arrived in China. Buddhism does not allow its believers to harm animals, so meat, eggs and fish are forbidden in their diet. The delicious, young bamboo shoot took their place. Ever since, it has been a traditional dish on the Chinese dinner table, especially in the south.

Bamboo is not only the symbol of a gentleman, but also has an important role in Buddhism. In the first century, this philosophy arrived in China. Buddhism does not allow its believers to harm animals, so meat, eggs and fish are forbidden in their diet. The delicious, young bamboo shoot took their place. Ever since, it has been a traditional dish on the Chinese dinner table, especially in the south.

But China is not the only country where bamboo is part of a popular meal. In Nepal and the north-eastern states of India, bamboo shoots are spiced with turmeric and served as a curry with other vegetables, especially potatoes. In Indonesia, the plant is cooked in coconut milk, while it can also be made into a soft drink or an alcoholic one.

Of course, it’s not only people that enjoy eating bamboo, but many animals too, most famously the giant panda, not to mention the rats that eat its fruit and flowers. In Africa, mountain gorillas not only eat it but drink the sap when it is alcoholic.

It is, perhaps, surprising that both people and animals eat so much bamboo because it contains a toxin that turns into cyanide in the intestines. Some animals have adapted to this, so that the golden bamboo lemur can eat many times the quantity that would kill an adult man. And, as if all that were not enough, bamboo has long been used to make paper too!

It is, perhaps, surprising that both people and animals eat so much bamboo because it contains a toxin that turns into cyanide in the intestines. Some animals have adapted to this, so that the golden bamboo lemur can eat many times the quantity that would kill an adult man. And, as if all that were not enough, bamboo has long been used to make paper too!

But what is bamboo? Why is it so different from other plants? In fact, it’s a kind of grass. Giant bamboos are its largest members and are one of the fastest-growing plants in the world, with some plants increasing their height by a metre in just twenty-four hours (although it’s more usual for them to grow between three and ten centimetres in that time). Some types can grow to thirty metres tall, while others only reach ten or fifteen centimetres. There are, in fact, about 1,450 species of bamboo growing on every continent except Europe. They can survive at temperatures as cold as -30° Centigrade and, of course, do very well in hot, wet climates too.

Most bamboo species flower only very occasionally. Many flower once every 60 to 120 years. Then all the plants in a particular species will flower for several years, no matter where they are in the world, whether in the icy south of Chile or the hot and humid jungles of Thailand. This strange phenomenon where its flowering does not depend on its environment, suggests a sort of internal ‘alarm clock’ in the plant cells which directs the plant to transfer its energy to flowering and away from growth. But how and why this happens are mysteries.

Most bamboo species flower only very occasionally. Many flower once every 60 to 120 years. Then all the plants in a particular species will flower for several years, no matter where they are in the world, whether in the icy south of Chile or the hot and humid jungles of Thailand. This strange phenomenon where its flowering does not depend on its environment, suggests a sort of internal ‘alarm clock’ in the plant cells which directs the plant to transfer its energy to flowering and away from growth. But how and why this happens are mysteries.

One way to explain mass flowering is that the bamboo ensures its survival by producing so much fruit that its predators – rats – simply cannot eat it all. What’s more, because the time between the seasons when it flowers is so much longer than the lifespan of the rats, bamboos can reduce their populations by starving them to death during the period when the bamboo doesn’t flower.

Another theory argues that periodic flowering followed by the deaths of all the adult bamboo plants has evolved as a way to allow young plants to grow, without any competition from older and stronger plants. The dead plants create a lot of wood and become a target for lightning strikes, causing huge fires that leave the ground empty and ready for new bamboo seeds to grow.

However, neither of these ideas really explains the very strange circumstances of the bamboo flowering. Why is the period between flowering seasons ten times longer than the lifespan of the rats that eat the flowers? And why would the bamboo be the only plant to depend on lightning to ensure its survival? Lightning is, anyway, not very dependable. Most forest fires are, in fact, caused by people.

However, neither of these ideas really explains the very strange circumstances of the bamboo flowering. Why is the period between flowering seasons ten times longer than the lifespan of the rats that eat the flowers? And why would the bamboo be the only plant to depend on lightning to ensure its survival? Lightning is, anyway, not very dependable. Most forest fires are, in fact, caused by people.

Whatever the answer may be to this puzzle, the mass fruiting has terrible economic and ecological results. The huge increase in fruit usually causes a dramatic rise in the rat populations, which spread disease and starvation among farmers.

There are many examples of this but one of the worst is in the subcontinent, when the bamboo flowers every thirty to thirty-five years. The deaths of the bamboo plants after they flower means the local people lose their building material, and the sudden increase in bamboo fruit leads to the rapid growth of the rat population. The animals eat not just the bamboo fruit but the crops in the fields and the food stored in warehouses. They also carry dangerous diseases, like typhus, typhoid and even plague.

Both the Venus flytrap and bamboo are plants but the ways they get food, their flowers and the conditions they need to thrive are so different from each other. Perhaps now you can understand some of the difficulties of classifying these very different organisms as essentially similar.

If you want to watch some videos on this topic, you can click on the links to YouTube videos below.

If you want to answer questions on this article to test how much you understand, you can click on the green box: Finished Reading?

Videos :

1. What is Taxonomy? (2:13)

2. Aristotle and Early Classification (2:03)

3. Chlorophyll (2:34)

4. Lichen (4:12)

5. Moss (5:26)

6. The Day of the Triffids (4:15)

7. Man-Eating Plants (5:50)

8. Hungry Venus Flytrap (2:50)

9. Drosera (1:23)

10. Vietnam Bamboo Village (6:37)

11. Bamboo Fruits (3:16)

12. Why Bamboo is Different from other Plants (7:44)

Aristotle as long ago as 350 B.C. began

Aristotle as long ago as 350 B.C. began  In 1951, John Wyndham published his successful novel, ‘The Day of the Triffids’, which was also recorded for the radio, made into a Hollywood film and

In 1951, John Wyndham published his successful novel, ‘The Day of the Triffids’, which was also recorded for the radio, made into a Hollywood film and  The edges of the leaves are covered with hairs, which close to prevent large

The edges of the leaves are covered with hairs, which close to prevent large  Anyway, while Drosera catch smaller, flying insects, flytraps are only interested in larger,

Anyway, while Drosera catch smaller, flying insects, flytraps are only interested in larger,  There are many

There are many  Bamboo is not only the symbol of a gentleman, but also has an important role in Buddhism. In the first century, this philosophy arrived in China. Buddhism does not allow its believers to harm animals, so meat, eggs and fish are forbidden in their diet. The delicious, young bamboo shoot took their place. Ever since, it has been a traditional dish on the Chinese dinner table, especially in the south.

Bamboo is not only the symbol of a gentleman, but also has an important role in Buddhism. In the first century, this philosophy arrived in China. Buddhism does not allow its believers to harm animals, so meat, eggs and fish are forbidden in their diet. The delicious, young bamboo shoot took their place. Ever since, it has been a traditional dish on the Chinese dinner table, especially in the south. It is, perhaps, surprising that both people and animals eat so much bamboo because it contains a

It is, perhaps, surprising that both people and animals eat so much bamboo because it contains a  Most bamboo

Most bamboo  However, neither of these ideas really explains the very strange circumstances of the bamboo flowering. Why is the period between flowering seasons ten times longer than the lifespan of the rats that eat the flowers? And why would the bamboo be the only plant to depend on

However, neither of these ideas really explains the very strange circumstances of the bamboo flowering. Why is the period between flowering seasons ten times longer than the lifespan of the rats that eat the flowers? And why would the bamboo be the only plant to depend on