Course description

Marie Curie – Scientist, Feminist & Patriot

There are not many women’s names in the history of science that are more easily recognized than Marie Curie’s. Nearly ninety years after her death, she remains a shining light in the fields of physics and chemistry. But she is also a hero to many people all around the world, even in the twenty-first century, because of the difficulties she overcame to achieve so much in her lifetime. She was a female scientist when many universities did not accept women as students or allow them to speak to scientific societies. She was a foreigner in France, called a Jew – although she was not – to damage her career and reputation.

There are not many women’s names in the history of science that are more easily recognized than Marie Curie’s. Nearly ninety years after her death, she remains a shining light in the fields of physics and chemistry. But she is also a hero to many people all around the world, even in the twenty-first century, because of the difficulties she overcame to achieve so much in her lifetime. She was a female scientist when many universities did not accept women as students or allow them to speak to scientific societies. She was a foreigner in France, called a Jew – although she was not – to damage her career and reputation.

In the cold Paris winters, she had to wear all the clothes she owned to keep warm when she was a student because she did not have enough money to pay for her university courses and to buy wood for a fire. And, in Poland, she is remembered for her patriotism and her support for her country’s independence. In truth, she was a remarkable woman.

Maria SkƗodowska was born in Warsaw, now capital of Poland, in 1867. Her family’s property and wealth had been seized by the Russian government as a punishment for their support of Polish independence and, so, Maria had to struggle to get an education. She made a deal with her elder sister, BronisƗawa, that she would work to help pay for her sister’s education in Paris, if BronisƗawa would later help pay for Maria’s.

She took a job as a governess in the home of the parents of Kazimierz Zorawski, teaching his younger brothers and sisters. Unfortunately, Maria and the oldest son fell madly in love but Kazimierz’s parents would not agree to him marrying the poor girl working in their house. The young man later went on to become a famous mathematician and Rector of the University of Kraków, the historical capital of Poland. The story goes that Kazimierz, as an old man, would sit in front of a statue of Maria in the 1930s and spend hours looking at her in his old age. We can only guess what the young man meant to Maria.

While Maria remained in Poland, she could not study at a regular university, as these were not open to women. Instead, she got admitted to an unofficial institution, called the Flying University, set up by academics struggling for Polish independence. This admitted women.

It was not until 1891 that she had enough money to make the trip to Paris, where she lived with her sister before getting a tiny room of her own near to the University of Paris, which accepted her as a student of Physics. Life was hard for Maria – or ‘Marie’, as she called herself in France – because she could only afford the fees with great difficulty. Perhaps it was lucky, then, that she often forgot to eat because she was so focused on her studies. But her hard work earned her a scholarship to do her Master’s degree at the same university.

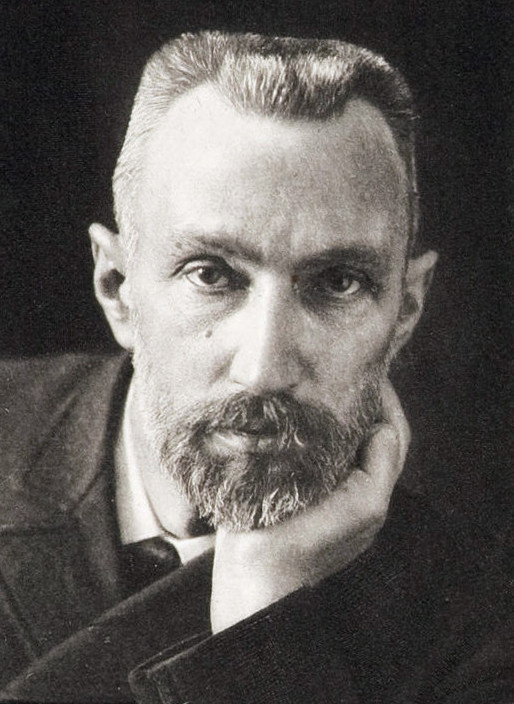

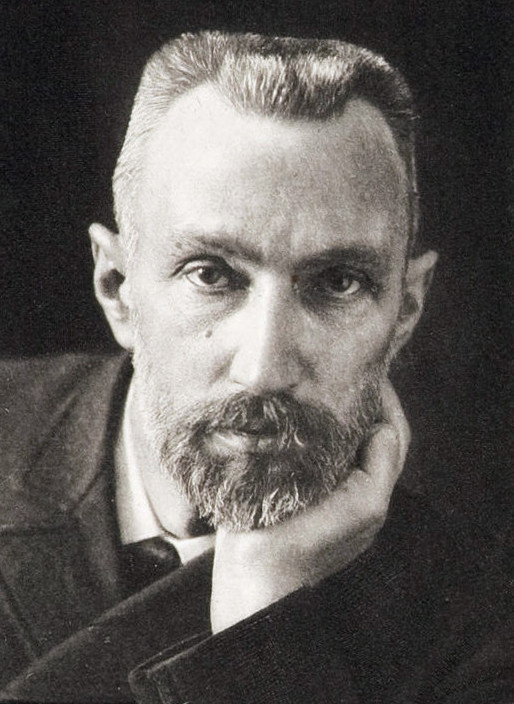

Shortly afterwards, Pierre Curie offered her a job in his laboratory. Soon, they became close, united by their shared passion for science. However, Marie only agreed to marry Pierre when he said he would move to Poland with her, if she wanted to return to her native country. At the wedding ceremony, Marie wore a blue dress that she later wore in her laboratory. There was no mention of God at their wedding either.

Marie briefly returned to Poland on her own to apply to the University of Kraków to do a doctorate. She was refused because she was a woman. Pierre persuaded her to return to France, where he was now a Professor at the University of Paris, to complete it there.

Discoveries came thick and fast.

In 1895, the German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen had discovered X-rays and, a few years later, Henri Becquerel was able to isolate the element, uranium. Marie Curie identified thorium, polonium – named after her beloved Poland – and radium. With the help of her husband, she was able to show that uranium gave off energy. Until that time, scientists believed that atoms from single elements were indivisible, the smallest units known to humankind, but, if one gave off energy, it clearly could not be. (Ernest Rutherford was awarded the Nobel Prize for splitting the atom in 1908.)

Marie Curie now set about isolating radium and polonium. She already knew that thorium and radium were ‘radioactive’, a term that Pierre and she originated and made popular. She also understood that these elements were far more radioactive than uranium, emitting between two and four times the energy of uranium. But it was no easy job. Curie needed a ton of ore to collect just 0.1 gram of radium. She only achieved this in 1910.

However, Marie and Pierre were starting to get noticed in the global scientific community. In 1902, they were invited to give a talk on radioactivity to the Royal Institute in London – only, Marie, a woman, was not allowed to speak.

A year later, Pierre and Marie shared the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1903 with Henri Becquerel. In fact, the Prize was originally going to be shared between the two men, but Pierre heard that Marie was not to get the award and complained to the Nobel Committee. When her husband died in a road accident – he was very absent-minded, always thinking about his work and never minding the traffic – in 1906, Marie was offered his Professorship at the University of Paris and, so, became the first female Professor in the eight hundred years of the University’s history.

In 1911, Marie was awarded a second Nobel Prize – this time in Chemistry – for isolating radium. She was the first person to win two Prizes and the only one to get two academic awards (although Linus Pauling got both a Prize in Chemistry and another in Peace many years later). Her research in this area had very practical consequences for the treatment of cancer and, so, human health, as she quickly realized that radium destroyed diseased cells that were developing tumours faster than healthy ones. This, of course, led to radiotherapy for cancer patients.

In the First World War, Marie Curie contributed to the war effort by creating mobile X-ray units that could travel to the frontline and be used with wounded soldiers there. She made sure that thousands of hospitals in France had X-ray units too. It has been estimated that as many as a million lives were saved because of this work.

It is strange, then, that the French government did not give her any awards for her work. This was not actually because she was a woman, but for other reasons. In the first place, many French right-wingers were against her because she was a foreigner. France was very xenophobic at the time. Many newspapers called her a Jew – which was not true – as well.

Marie also had an affair with a married Frenchman, who was five years younger than her. The newspapers were horrible about it and she could not return to her home because of angry crowds waiting outside for her.

Marie Curie died in 1934 of an illness, caused by radiation. Neither she, nor Pierre, nor her daughter, realized that carrying radium around in one’s pocket was a serious health risk. Her daughter, Irène, and her son-in-law, Frédéric Joliot-Curie, both of whom were also awarded Nobel Prizes, died from the same cause. However, right up until her death, Marie Curie never mentioned a possible link between radium and cancer.

If you want to watch some videos on this topic, you can click on the links to YouTube videos below.

If you want to answer questions on this article to test how much you understand, you can click on the green box: Finished Reading?

Videos:

1. Jamie Gallagher Discusses about the Radioactive Woman Marie Curie (4:23)

2. Marie Curie – Scientist (3:04)

3. The Genius of Marie Curie (5:03)

4. What Exactly Happened to Marie Curie? (3:03)

5. This Pioneer of Radioactivity Died In 1934 (7:32)

6. Biography of Marie Curie for Kids (8:10)

7. Marie Curie's Speech at the Nobel Banquet (2:55)

There are not many women’s names in the history of science that are more easily recognized than Marie Curie’s. Nearly ninety years after her death, she remains a shining light in the fields of physics and chemistry. But she is also a hero to many people all around the world, even in the twenty-first century, because of the difficulties she

There are not many women’s names in the history of science that are more easily recognized than Marie Curie’s. Nearly ninety years after her death, she remains a shining light in the fields of physics and chemistry. But she is also a hero to many people all around the world, even in the twenty-first century, because of the difficulties she