Course description

Clouds & Rivers – Supplying the World with Water

Clouds

“I wandered lonely as a cloud that floats on high” – William Wordsworth, nineteenth century poet

512px-Cirrus_clouds_mar08.jpg (512×341)Huge bits of half-frozen steam floating in the sky. That’s probably the best non-technical description of clouds. At a more minute level, they are made up of tiny particles of frozen water, called aerosols which, together in countless billions, make a cloud. The water gets in the sky through evaporation, the process in which liquid becomes gas, usually because of heat. This could be water rising from the seas and oceans or lakes; or it could be evaporation from places with a lot of plant life, typically a tropical forest. The source of heat is almost always the sun but some evaporation of water is from thermal and volcanic sources.

The size and shape of the clouds, once they are up there, depend on a number of factors like air temperature, wind speed and direction, humidity and what the clouds are floating over at any given moment, e.g. over water, over mountains, over tropical forest, over a big city, etc. Both the shape and the size are very variable but some clouds can contain millions of tons of water. A fact that is hard to believe until you have stood in a heavy tropical downpour.

As we all know, clouds come in an infinite variety but they are classed into finite categories. The different kinds are too many to list here but they are usually made up of two classifications. So, for example, we can start with four basic types: cirrus (whisps); stratus (a layer); nimbus (ready to rain); cumulus (shaped like a hill). If we combine two of these names like ‘stratus’ and ‘nimbus’ to give ‘nimbostratus’ this would be the right name for a ‘layer of rainy cloud’.

And rain is what clouds are really all about. They are a key stage in the water cycle that sends water round and round to keep the planet working. And they are the only stage when the water is, for a time, not water but a kind of steam or lots of little bits of ice, depending on how you like to see it.

Most clouds form in the Earth’s lower atmosphere or ‘troposphere’. In this way, the rain they drop reaches the ground before evaporating into the air once more. Sometimes clouds can be found in the Earth’s upper atmosphere but much more common is cloud that touches the ground which, really, is fog. Fog, if seen as a cloud, is ‘stratus’.

Cloud has two very dramatic friends. These are thunder and lightning. When some clouds get very full of rain, they become electrically charged and quite heavy. When they hit each other, the crash causes both sound and electricity to be let out. The sound is the thunder and the electricity is the lightning. It’s very exciting to watch an electric storm but it can be quite dangerous. One electric storm releases more electricity than a whole city can use in a month. Unfortunately, it is not possible to ‘catch’ and use these explosions of electricity for heating, lighting and power.

There are two basic kinds of lightning: ‘fork’ and ‘sheet’; fork lightning, which shoots towards the ground in an angry streak, is the dangerous one. Recently, in Latin America, three members of the same football team were killed by one streak of lightning. This happened in a mountain city and close to the Equator, which seems to be the recipe for lightning. Tropical warmth meeting cold mountain air produces a lot of electric storms. Colombia, where the three footballers were killed, is the second most lightning-hit country in the world; number one is the Congo in Africa.

Lightning may be what triggered life on our planet. Scientists have suggested that running a strong electric charge through the warm chemicals and minerals on the Earth’s surface could be a way to start biological forms.

Clouds are a part of everyday life for most of us and, for some of us, they are very important. They make flying planes more difficult and dangerous and they can certainly spoil a day at the beach but, in times past, they were a way for people to find their home island, especially in tropical waters. Every island has a cloud rising over it like a tall column. It can be seen from a distance of one hundred kilometers, sometimes more. An experienced sailor can recognize which island it signals and by sailing from island to island, small boats in, for example, Polynesia can travel thousands of kilometers, often out of sight of land.

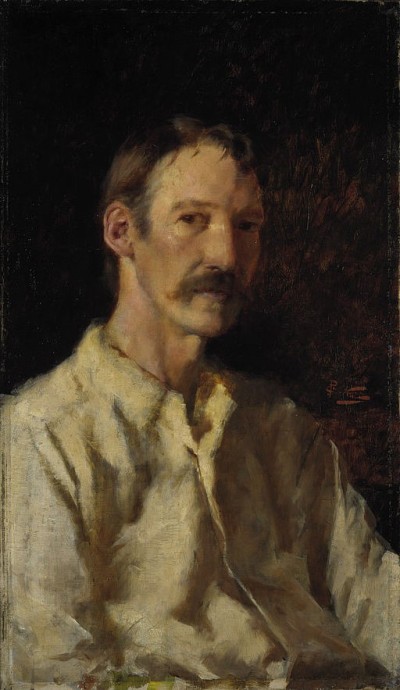

512px-MountRedoubtEruption.jpg (512×345)In human psychology, clouds represent ‘confusion’ and ‘depression’, as in the expression ‘don’t cloud the issue’. The singer, Amy Winehouse, described her terrible depression as feeling like she had a ‘cloud over her head’.

But clouds now have a worse association than depression. Since the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August of 1945, the immense mushroom cloud that shot into the air after the bombs exploded has become a symbol of human-made disaster and even the end of the world. (Not all mushroom clouds, however, come from nuclear explosions. The one in the picture is from a volcano.)

Life on Earth may have started in the clouds and the world may end with a cloud as well.

The Importance of Rivers

“All the rivers run to the sea, but the sea is not full;

To the place from where the rivers flow, there they flow again.” Ecclesiastes 1: 7

Rivers, long or short, wide or narrow, limpid or muddy, are a vital part of the Earth’s delicately balanced water system that also takes in the seas and oceans, lakes, clouds and rain. If water is the life-blood of planet Earth, then rivers are the arteries and veins. The rivers carry rainwater collected from mountains and natural basins. These are called watersheds and are the source or point of origin of almost all rivers.

The rivers then run to their mouths, the point at which they reach the sea, a lake or a bigger river. Rivers that feed into bigger rivers are called ‘tributaries’. By definition, rivers are natural, not man-made like canals. And that’s about as precise as the definition gets: a natural waterway, coming from a source and arriving at its mouth. If this poses the question – when is a stream too big to be a stream and, so, becomes a river? – There is no facile answer. It just depends on what local people tend to call it.

However, we do have some hard facts. Let’s establish, first of all, that the Nile, in Africa, is the longest river in the world, starting from its source in Uganda and debouching into the Mediterranean, several thousand kilometers to the north. The next longest is the Amazon in South America followed by the Yangtze in China. But, in all fairness, length is not the only criterion by which we can judge rivers. We can also talk about sheer volume of water.

This is like asking not ‘who is the tallest person in the room?’ but ‘who is the fattest?’ The Amazon wins this one hands down. It debouches so much river water into the Atlantic that there is fresh water, not salt, out of sight of the coast, kilometers out to sea. The second biggest by volume is the Ganges in India; and then the Congo in Africa.

The Ganges, by the way, is also an example of a sacred river; in this case for Hindus. Its waters are considered spiritually cleansing. Unfortunately, they are not physically cleansing as the Ganges is, these days, a very polluted and insanitary river.

There are many other examples of sacred rivers but to give just one more – the River Jordan in the Middle East – a river of enormous importance to Christians for baptism ceremonies and, these days, the subject of dispute between Israel and several neighboring countries, all wanting its waters for their agriculture.

And it is their connection to agriculture, especially for irrigation, that has made rivers so central to human civilization from its beginnings eight to ten thousand years ago. Clearly, growing crops next to or very close to a river guarantees well watered and well drained land even if the rains fail. Furthermore, rivers often deposit rich mud (called ‘silt’) along their banks, washed down from further upstream.

The silt makes highly productive soil which explains why a very narrow strip of farmland on either bank of the Nile allows Egyptian farmers to produce very large crops that feed the tens of millions who live in and around the capital, Cairo.

And, then, there’s another advantage to rivers. When you want to ship your crops or animals to market, and the bigger market will usually be downstream, you can put everything on a boat and just float it down to the nearest town or city, no fuel or hard work needed. Naturally, this kind of transport can be used by anybody, not just farmers going to market but tradesmen and their goods, government officials or private travelers. Rivers were the first catalyst to long-distance trade and communication and were a little safer than the roads; though river pirates are not unheard of, even today.

So, rivers make for great transport routes if you’re going their way; but, what if you don’t want to follow the course of the river but just to cross it? Originally, there were two ways, fords or ferries. Fords are the natural shallow points in a river, where it might be low and slow enough for people and animals to wade across. Often, local people would improve a ford by putting stones into it to make it even shallower.

Ferries were just little boats, frequently attached to both banks by a rope or chain tied to a tree on either side. Neither method was ideal though, so, the art of bridge building developed. At first, it was hard to make strong, long bridges that would allow a heavy cart to cross safely, so towns were situated a long way up the river from the mouth but, as techniques improved in the last thousand years or so, cities started to appear very close to the sea. In the case of Budapest, the capital of Hungary, the building of good bridges across the River Danube united the formerly separate towns of Buda on one bank and Pest on the other.

And it is this difficulty in crossing them that makes rivers good natural barriers. This is why rivers often mark the border between two countries, like the Rio Grande that marks the border between Mexico and the U.S.A. Even as recently as the Second World War, whole armies could be delayed for weeks and even months if the bridges were down and the enemy was waiting, armed and ready on the other bank.

Finally, ‘the river’ has always been a strong theme and symbol in art and literature, with Mark Twain’s ‘Huckleberry Finn’, set on the Mississippi River in the Southern U.S.A., and Joseph Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’, set on the Congo in central Africa, being just two examples. The river often represents change and the passage of time. But, more than anything, it represents ‘life’ as it travels from its source or ‘birth’ to its end and ‘burial’ in the sea only to flow again through the clouds to its place of origin.

An eternal cycle.

If you want to watch some videos on this topic, you can click on the links to YouTube videos below.

If you want to answer questions on this article to test how much you understand, you can click on the green box: Finished Reading?

Videos :

1. How Aerosols lead to Extreme Rainfall (3:58)

2. Types of Clouds- Cirrus, Cumulus, Stratus, Nimbus (5:54)

3. ‘Nile’ – Know about the World’s Longest River (1:18)

4. The Story of River Ganga (8:18)

5. Danube River (2:48)

512px-Cirrus_clouds_mar08.jpg (512×341)Huge bits of half-frozen steam floating in the sky. That’s probably the best non-technical description of clouds. At a more minute level, they are made up of tiny particles of frozen water, called aerosols which, together in countless billions, make a cloud. The water gets in the sky through evaporation, the process in which liquid becomes gas, usually because of heat. This could be water rising from the seas and oceans or lakes; or it could be evaporation from places with a lot of plant life, typically a tropical forest. The source of heat is almost always the sun but some evaporation of water is from thermal and volcanic sources.

The size and shape of the clouds, once they are up there, depend on a number of factors like air temperature, wind speed and direction, humidity and what the clouds are floating over at any given moment, e.g. over water, over mountains, over tropical forest, over a big city, etc. Both the shape and the size are very variable but some clouds can contain millions of tons of water. A fact that is hard to believe until you have stood in a heavy tropical downpour.

As we all know, clouds come in an infinite variety but they are classed into finite categories. The different kinds are too many to list here but they are usually made up of two classifications. So, for example, we can start with four basic types: cirrus (whisps); stratus (a layer); nimbus (ready to rain); cumulus (shaped like a hill). If we combine two of these names like ‘stratus’ and ‘nimbus’ to give ‘nimbostratus’ this would be the right name for a ‘layer of rainy cloud’.

And rain is what clouds are really all about. They are a key stage in the water cycle that sends water round and round to keep the planet working. And they are the only stage when the water is, for a time, not water but a kind of steam or lots of little bits of ice, depending on how you like to see it.

Most clouds form in the Earth’s lower atmosphere or ‘troposphere’. In this way, the rain they drop reaches the ground before evaporating into the air once more. Sometimes clouds can be found in the Earth’s upper atmosphere but much more common is cloud that touches the ground which, really, is fog. Fog, if seen as a cloud, is ‘stratus’.

Cloud has two very dramatic friends. These are thunder and lightning. When some clouds get very full of rain, they become electrically charged and quite heavy. When they hit each other, the crash causes both sound and electricity to be let out. The sound is the thunder and the electricity is the lightning. It’s very exciting to watch an electric storm but it can be quite dangerous. One electric storm releases more electricity than a whole city can use in a month. Unfortunately, it is not possible to ‘catch’ and use these explosions of electricity for heating, lighting and power.

There are two basic kinds of lightning: ‘fork’ and ‘sheet’; fork lightning, which shoots towards the ground in an angry streak, is the dangerous one. Recently, in Latin America, three members of the same football team were killed by one streak of lightning. This happened in a mountain city and close to the Equator, which seems to be the recipe for lightning. Tropical warmth meeting cold mountain air produces a lot of electric storms. Colombia, where the three footballers were killed, is the second most lightning-hit country in the world; number one is the Congo in Africa.

Lightning may be what triggered life on our planet. Scientists have suggested that running a strong electric charge through the warm chemicals and minerals on the Earth’s surface could be a way to start biological forms.

Clouds are a part of everyday life for most of us and, for some of us, they are very important. They make flying planes more difficult and dangerous and they can certainly spoil a day at the beach but, in times past, they were a way for people to find their home island, especially in tropical waters. Every island has a cloud rising over it like a tall column. It can be seen from a distance of one hundred kilometers, sometimes more. An experienced sailor can recognize which island it signals and by sailing from island to island, small boats in, for example, Polynesia can travel thousands of kilometers, often out of sight of land.

512px-MountRedoubtEruption.jpg (512×345)In human psychology, clouds represent ‘confusion’ and ‘depression’, as in the expression ‘don’t cloud the issue’. The singer, Amy Winehouse, described her terrible depression as feeling like she had a ‘cloud over her head’.

But clouds now have a worse association than depression. Since the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August of 1945, the immense mushroom cloud that shot into the air after the bombs exploded has become a symbol of human-made disaster and even the end of the world. (Not all mushroom clouds, however, come from nuclear explosions. The one in the picture is from a volcano.)

Life on Earth may have started in the clouds and the world may end with a cloud as well.

The Importance of Rivers

“All the rivers run to the sea, but the sea is not full;

To the place from where the rivers flow, there they flow again.” Ecclesiastes 1: 7

Rivers, long or short, wide or narrow, limpid or muddy, are a vital part of the Earth’s delicately balanced water system that also takes in the seas and oceans, lakes, clouds and rain. If water is the life-blood of planet Earth, then rivers are the arteries and veins. The rivers carry rainwater collected from mountains and natural basins. These are called watersheds and are the source or point of origin of almost all rivers.

The rivers then run to their mouths, the point at which they reach the sea, a lake or a bigger river. Rivers that feed into bigger rivers are called ‘tributaries’. By definition, rivers are natural, not man-made like canals. And that’s about as precise as the definition gets: a natural waterway, coming from a source and arriving at its mouth. If this poses the question – when is a stream too big to be a stream and, so, becomes a river? – There is no facile answer. It just depends on what local people tend to call it.

However, we do have some hard facts. Let’s establish, first of all, that the Nile, in Africa, is the longest river in the world, starting from its source in Uganda and debouching into the Mediterranean, several thousand kilometers to the north. The next longest is the Amazon in South America followed by the Yangtze in China. But, in all fairness, length is not the only criterion by which we can judge rivers. We can also talk about sheer volume of water.

This is like asking not ‘who is the tallest person in the room?’ but ‘who is the fattest?’ The Amazon wins this one hands down. It debouches so much river water into the Atlantic that there is fresh water, not salt, out of sight of the coast, kilometers out to sea. The second biggest by volume is the Ganges in India; and then the Congo in Africa.

The Ganges, by the way, is also an example of a sacred river; in this case for Hindus. Its waters are considered spiritually cleansing. Unfortunately, they are not physically cleansing as the Ganges is, these days, a very polluted and insanitary river.

There are many other examples of sacred rivers but to give just one more – the River Jordan in the Middle East – a river of enormous importance to Christians for baptism ceremonies and, these days, the subject of dispute between Israel and several neighboring countries, all wanting its waters for their agriculture.

And it is their connection to agriculture, especially for irrigation, that has made rivers so central to human civilization from its beginnings eight to ten thousand years ago. Clearly, growing crops next to or very close to a river guarantees well watered and well drained land even if the rains fail. Furthermore, rivers often deposit rich mud (called ‘silt’) along their banks, washed down from further upstream.

The silt makes highly productive soil which explains why a very narrow strip of farmland on either bank of the Nile allows Egyptian farmers to produce very large crops that feed the tens of millions who live in and around the capital, Cairo.

And, then, there’s another advantage to rivers. When you want to ship your crops or animals to market, and the bigger market will usually be downstream, you can put everything on a boat and just float it down to the nearest town or city, no fuel or hard work needed. Naturally, this kind of transport can be used by anybody, not just farmers going to market but tradesmen and their goods, government officials or private travelers. Rivers were the first catalyst to long-distance trade and communication and were a little safer than the roads; though river pirates are not unheard of, even today.

So, rivers make for great transport routes if you’re going their way; but, what if you don’t want to follow the course of the river but just to cross it? Originally, there were two ways, fords or ferries. Fords are the natural shallow points in a river, where it might be low and slow enough for people and animals to wade across. Often, local people would improve a ford by putting stones into it to make it even shallower.

Ferries were just little boats, frequently attached to both banks by a rope or chain tied to a tree on either side. Neither method was ideal though, so, the art of bridge building developed. At first, it was hard to make strong, long bridges that would allow a heavy cart to cross safely, so towns were situated a long way up the river from the mouth but, as techniques improved in the last thousand years or so, cities started to appear very close to the sea. In the case of Budapest, the capital of Hungary, the building of good bridges across the River Danube united the formerly separate towns of Buda on one bank and Pest on the other.

And it is this difficulty in crossing them that makes rivers good natural barriers. This is why rivers often mark the border between two countries, like the Rio Grande that marks the border between Mexico and the U.S.A. Even as recently as the Second World War, whole armies could be delayed for weeks and even months if the bridges were down and the enemy was waiting, armed and ready on the other bank.

Finally, ‘the river’ has always been a strong theme and symbol in art and literature, with Mark Twain’s ‘Huckleberry Finn’, set on the Mississippi River in the Southern U.S.A., and Joseph Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’, set on the Congo in central Africa, being just two examples. The river often represents change and the passage of time. But, more than anything, it represents ‘life’ as it travels from its source or ‘birth’ to its end and ‘burial’ in the sea only to flow again through the clouds to its place of origin.

An eternal cycle.

If you want to watch some videos on this topic, you can click on the links to YouTube videos below.

If you want to answer questions on this article to test how much you understand, you can click on the green box: Finished Reading?

Videos :

1. How Aerosols lead to Extreme Rainfall (3:58)

2. Types of Clouds- Cirrus, Cumulus, Stratus, Nimbus (5:54)

3. ‘Nile’ – Know about the World’s Longest River (1:18)

4. The Story of River Ganga (8:18)

5. Danube River (2:48)

512px-Cirrus_clouds_mar08.jpg (512×341)Huge bits of half-frozen steam floating in the sky. That’s probably the best non-technical description of clouds. At a more minute level, they are made up of tiny particles of frozen water, called aerosols which, together in countless billions, make a cloud. The water gets in the sky through evaporation, the process in which liquid becomes gas, usually because of heat. This could be water rising from the seas and oceans or lakes; or it could be evaporation from places with a lot of plant life, typically a tropical forest. The source of heat is almost always the sun but some evaporation of water is from thermal and volcanic sources.

The size and shape of the clouds, once they are up there, depend on a number of factors like air temperature, wind speed and direction, humidity and what the clouds are floating over at any given moment, e.g. over water, over mountains, over tropical forest, over a big city, etc. Both the shape and the size are very variable but some clouds can contain millions of tons of water. A fact that is hard to believe until you have stood in a heavy tropical downpour.

As we all know, clouds come in an infinite variety but they are classed into finite categories. The different kinds are too many to list here but they are usually made up of two classifications. So, for example, we can start with four basic types: cirrus (whisps); stratus (a layer); nimbus (ready to rain); cumulus (shaped like a hill). If we combine two of these names like ‘stratus’ and ‘nimbus’ to give ‘nimbostratus’ this would be the right name for a ‘layer of rainy cloud’.

And rain is what clouds are really all about. They are a key stage in the water cycle that sends water round and round to keep the planet working. And they are the only stage when the water is, for a time, not water but a kind of steam or lots of little bits of ice, depending on how you like to see it.

Most clouds form in the Earth’s lower atmosphere or ‘troposphere’. In this way, the rain they drop reaches the ground before evaporating into the air once more. Sometimes clouds can be found in the Earth’s upper atmosphere but much more common is cloud that touches the ground which, really, is fog. Fog, if seen as a cloud, is ‘stratus’.

Cloud has two very dramatic friends. These are thunder and lightning. When some clouds get very full of rain, they become electrically charged and quite heavy. When they hit each other, the crash causes both sound and electricity to be let out. The sound is the thunder and the electricity is the lightning. It’s very exciting to watch an electric storm but it can be quite dangerous. One electric storm releases more electricity than a whole city can use in a month. Unfortunately, it is not possible to ‘catch’ and use these explosions of electricity for heating, lighting and power.

There are two basic kinds of lightning: ‘fork’ and ‘sheet’; fork lightning, which shoots towards the ground in an angry streak, is the dangerous one. Recently, in Latin America, three members of the same football team were killed by one streak of lightning. This happened in a mountain city and close to the Equator, which seems to be the recipe for lightning. Tropical warmth meeting cold mountain air produces a lot of electric storms. Colombia, where the three footballers were killed, is the second most lightning-hit country in the world; number one is the Congo in Africa.

Lightning may be what triggered life on our planet. Scientists have suggested that running a strong electric charge through the warm chemicals and minerals on the Earth’s surface could be a way to start biological forms.

Clouds are a part of everyday life for most of us and, for some of us, they are very important. They make flying planes more difficult and dangerous and they can certainly spoil a day at the beach but, in times past, they were a way for people to find their home island, especially in tropical waters. Every island has a cloud rising over it like a tall column. It can be seen from a distance of one hundred kilometers, sometimes more. An experienced sailor can recognize which island it signals and by sailing from island to island, small boats in, for example, Polynesia can travel thousands of kilometers, often out of sight of land.

512px-MountRedoubtEruption.jpg (512×345)In human psychology, clouds represent ‘confusion’ and ‘depression’, as in the expression ‘don’t cloud the issue’. The singer, Amy Winehouse, described her terrible depression as feeling like she had a ‘cloud over her head’.

But clouds now have a worse association than depression. Since the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August of 1945, the immense mushroom cloud that shot into the air after the bombs exploded has become a symbol of human-made disaster and even the end of the world. (Not all mushroom clouds, however, come from nuclear explosions. The one in the picture is from a volcano.)

Life on Earth may have started in the clouds and the world may end with a cloud as well.

The Importance of Rivers

“All the rivers run to the sea, but the sea is not full;

To the place from where the rivers flow, there they flow again.” Ecclesiastes 1: 7

Rivers, long or short, wide or narrow, limpid or muddy, are a vital part of the Earth’s delicately balanced water system that also takes in the seas and oceans, lakes, clouds and rain. If water is the life-blood of planet Earth, then rivers are the arteries and veins. The rivers carry rainwater collected from mountains and natural basins. These are called watersheds and are the source or point of origin of almost all rivers.

The rivers then run to their mouths, the point at which they reach the sea, a lake or a bigger river. Rivers that feed into bigger rivers are called ‘tributaries’. By definition, rivers are natural, not man-made like canals. And that’s about as precise as the definition gets: a natural waterway, coming from a source and arriving at its mouth. If this poses the question – when is a stream too big to be a stream and, so, becomes a river? – There is no facile answer. It just depends on what local people tend to call it.

However, we do have some hard facts. Let’s establish, first of all, that the Nile, in Africa, is the longest river in the world, starting from its source in Uganda and debouching into the Mediterranean, several thousand kilometers to the north. The next longest is the Amazon in South America followed by the Yangtze in China. But, in all fairness, length is not the only criterion by which we can judge rivers. We can also talk about sheer volume of water.

This is like asking not ‘who is the tallest person in the room?’ but ‘who is the fattest?’ The Amazon wins this one hands down. It debouches so much river water into the Atlantic that there is fresh water, not salt, out of sight of the coast, kilometers out to sea. The second biggest by volume is the Ganges in India; and then the Congo in Africa.

The Ganges, by the way, is also an example of a sacred river; in this case for Hindus. Its waters are considered spiritually cleansing. Unfortunately, they are not physically cleansing as the Ganges is, these days, a very polluted and insanitary river.

There are many other examples of sacred rivers but to give just one more – the River Jordan in the Middle East – a river of enormous importance to Christians for baptism ceremonies and, these days, the subject of dispute between Israel and several neighboring countries, all wanting its waters for their agriculture.

And it is their connection to agriculture, especially for irrigation, that has made rivers so central to human civilization from its beginnings eight to ten thousand years ago. Clearly, growing crops next to or very close to a river guarantees well watered and well drained land even if the rains fail. Furthermore, rivers often deposit rich mud (called ‘silt’) along their banks, washed down from further upstream.

The silt makes highly productive soil which explains why a very narrow strip of farmland on either bank of the Nile allows Egyptian farmers to produce very large crops that feed the tens of millions who live in and around the capital, Cairo.

And, then, there’s another advantage to rivers. When you want to ship your crops or animals to market, and the bigger market will usually be downstream, you can put everything on a boat and just float it down to the nearest town or city, no fuel or hard work needed. Naturally, this kind of transport can be used by anybody, not just farmers going to market but tradesmen and their goods, government officials or private travelers. Rivers were the first catalyst to long-distance trade and communication and were a little safer than the roads; though river pirates are not unheard of, even today.

So, rivers make for great transport routes if you’re going their way; but, what if you don’t want to follow the course of the river but just to cross it? Originally, there were two ways, fords or ferries. Fords are the natural shallow points in a river, where it might be low and slow enough for people and animals to wade across. Often, local people would improve a ford by putting stones into it to make it even shallower.

Ferries were just little boats, frequently attached to both banks by a rope or chain tied to a tree on either side. Neither method was ideal though, so, the art of bridge building developed. At first, it was hard to make strong, long bridges that would allow a heavy cart to cross safely, so towns were situated a long way up the river from the mouth but, as techniques improved in the last thousand years or so, cities started to appear very close to the sea. In the case of Budapest, the capital of Hungary, the building of good bridges across the River Danube united the formerly separate towns of Buda on one bank and Pest on the other.

And it is this difficulty in crossing them that makes rivers good natural barriers. This is why rivers often mark the border between two countries, like the Rio Grande that marks the border between Mexico and the U.S.A. Even as recently as the Second World War, whole armies could be delayed for weeks and even months if the bridges were down and the enemy was waiting, armed and ready on the other bank.

Finally, ‘the river’ has always been a strong theme and symbol in art and literature, with Mark Twain’s ‘Huckleberry Finn’, set on the Mississippi River in the Southern U.S.A., and Joseph Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’, set on the Congo in central Africa, being just two examples. The river often represents change and the passage of time. But, more than anything, it represents ‘life’ as it travels from its source or ‘birth’ to its end and ‘burial’ in the sea only to flow again through the clouds to its place of origin.

An eternal cycle.

If you want to watch some videos on this topic, you can click on the links to YouTube videos below.

If you want to answer questions on this article to test how much you understand, you can click on the green box: Finished Reading?

Videos :

1. How Aerosols lead to Extreme Rainfall (3:58)

2. Types of Clouds- Cirrus, Cumulus, Stratus, Nimbus (5:54)

3. ‘Nile’ – Know about the World’s Longest River (1:18)

4. The Story of River Ganga (8:18)

5. Danube River (2:48)

512px-Cirrus_clouds_mar08.jpg (512×341)Huge bits of half-frozen steam floating in the sky. That’s probably the best non-technical description of clouds. At a more minute level, they are made up of tiny particles of frozen water, called aerosols which, together in countless billions, make a cloud. The water gets in the sky through evaporation, the process in which liquid becomes gas, usually because of heat. This could be water rising from the seas and oceans or lakes; or it could be evaporation from places with a lot of plant life, typically a tropical forest. The source of heat is almost always the sun but some evaporation of water is from thermal and volcanic sources.

The size and shape of the clouds, once they are up there, depend on a number of factors like air temperature, wind speed and direction, humidity and what the clouds are floating over at any given moment, e.g. over water, over mountains, over tropical forest, over a big city, etc. Both the shape and the size are very variable but some clouds can contain millions of tons of water. A fact that is hard to believe until you have stood in a heavy tropical downpour.

As we all know, clouds come in an infinite variety but they are classed into finite categories. The different kinds are too many to list here but they are usually made up of two classifications. So, for example, we can start with four basic types: cirrus (whisps); stratus (a layer); nimbus (ready to rain); cumulus (shaped like a hill). If we combine two of these names like ‘stratus’ and ‘nimbus’ to give ‘nimbostratus’ this would be the right name for a ‘layer of rainy cloud’.

And rain is what clouds are really all about. They are a key stage in the water cycle that sends water round and round to keep the planet working. And they are the only stage when the water is, for a time, not water but a kind of steam or lots of little bits of ice, depending on how you like to see it.

Most clouds form in the Earth’s lower atmosphere or ‘troposphere’. In this way, the rain they drop reaches the ground before evaporating into the air once more. Sometimes clouds can be found in the Earth’s upper atmosphere but much more common is cloud that touches the ground which, really, is fog. Fog, if seen as a cloud, is ‘stratus’.

Cloud has two very dramatic friends. These are thunder and lightning. When some clouds get very full of rain, they become electrically charged and quite heavy. When they hit each other, the crash causes both sound and electricity to be let out. The sound is the thunder and the electricity is the lightning. It’s very exciting to watch an electric storm but it can be quite dangerous. One electric storm releases more electricity than a whole city can use in a month. Unfortunately, it is not possible to ‘catch’ and use these explosions of electricity for heating, lighting and power.

There are two basic kinds of lightning: ‘fork’ and ‘sheet’; fork lightning, which shoots towards the ground in an angry streak, is the dangerous one. Recently, in Latin America, three members of the same football team were killed by one streak of lightning. This happened in a mountain city and close to the Equator, which seems to be the recipe for lightning. Tropical warmth meeting cold mountain air produces a lot of electric storms. Colombia, where the three footballers were killed, is the second most lightning-hit country in the world; number one is the Congo in Africa.

Lightning may be what triggered life on our planet. Scientists have suggested that running a strong electric charge through the warm chemicals and minerals on the Earth’s surface could be a way to start biological forms.

Clouds are a part of everyday life for most of us and, for some of us, they are very important. They make flying planes more difficult and dangerous and they can certainly spoil a day at the beach but, in times past, they were a way for people to find their home island, especially in tropical waters. Every island has a cloud rising over it like a tall column. It can be seen from a distance of one hundred kilometers, sometimes more. An experienced sailor can recognize which island it signals and by sailing from island to island, small boats in, for example, Polynesia can travel thousands of kilometers, often out of sight of land.

512px-MountRedoubtEruption.jpg (512×345)In human psychology, clouds represent ‘confusion’ and ‘depression’, as in the expression ‘don’t cloud the issue’. The singer, Amy Winehouse, described her terrible depression as feeling like she had a ‘cloud over her head’.

But clouds now have a worse association than depression. Since the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August of 1945, the immense mushroom cloud that shot into the air after the bombs exploded has become a symbol of human-made disaster and even the end of the world. (Not all mushroom clouds, however, come from nuclear explosions. The one in the picture is from a volcano.)

Life on Earth may have started in the clouds and the world may end with a cloud as well.

The Importance of Rivers

“All the rivers run to the sea, but the sea is not full;

To the place from where the rivers flow, there they flow again.” Ecclesiastes 1: 7

Rivers, long or short, wide or narrow, limpid or muddy, are a vital part of the Earth’s delicately balanced water system that also takes in the seas and oceans, lakes, clouds and rain. If water is the life-blood of planet Earth, then rivers are the arteries and veins. The rivers carry rainwater collected from mountains and natural basins. These are called watersheds and are the source or point of origin of almost all rivers.

The rivers then run to their mouths, the point at which they reach the sea, a lake or a bigger river. Rivers that feed into bigger rivers are called ‘tributaries’. By definition, rivers are natural, not man-made like canals. And that’s about as precise as the definition gets: a natural waterway, coming from a source and arriving at its mouth. If this poses the question – when is a stream too big to be a stream and, so, becomes a river? – There is no facile answer. It just depends on what local people tend to call it.

However, we do have some hard facts. Let’s establish, first of all, that the Nile, in Africa, is the longest river in the world, starting from its source in Uganda and debouching into the Mediterranean, several thousand kilometers to the north. The next longest is the Amazon in South America followed by the Yangtze in China. But, in all fairness, length is not the only criterion by which we can judge rivers. We can also talk about sheer volume of water.

This is like asking not ‘who is the tallest person in the room?’ but ‘who is the fattest?’ The Amazon wins this one hands down. It debouches so much river water into the Atlantic that there is fresh water, not salt, out of sight of the coast, kilometers out to sea. The second biggest by volume is the Ganges in India; and then the Congo in Africa.

The Ganges, by the way, is also an example of a sacred river; in this case for Hindus. Its waters are considered spiritually cleansing. Unfortunately, they are not physically cleansing as the Ganges is, these days, a very polluted and insanitary river.

There are many other examples of sacred rivers but to give just one more – the River Jordan in the Middle East – a river of enormous importance to Christians for baptism ceremonies and, these days, the subject of dispute between Israel and several neighboring countries, all wanting its waters for their agriculture.

And it is their connection to agriculture, especially for irrigation, that has made rivers so central to human civilization from its beginnings eight to ten thousand years ago. Clearly, growing crops next to or very close to a river guarantees well watered and well drained land even if the rains fail. Furthermore, rivers often deposit rich mud (called ‘silt’) along their banks, washed down from further upstream.

The silt makes highly productive soil which explains why a very narrow strip of farmland on either bank of the Nile allows Egyptian farmers to produce very large crops that feed the tens of millions who live in and around the capital, Cairo.

And, then, there’s another advantage to rivers. When you want to ship your crops or animals to market, and the bigger market will usually be downstream, you can put everything on a boat and just float it down to the nearest town or city, no fuel or hard work needed. Naturally, this kind of transport can be used by anybody, not just farmers going to market but tradesmen and their goods, government officials or private travelers. Rivers were the first catalyst to long-distance trade and communication and were a little safer than the roads; though river pirates are not unheard of, even today.

So, rivers make for great transport routes if you’re going their way; but, what if you don’t want to follow the course of the river but just to cross it? Originally, there were two ways, fords or ferries. Fords are the natural shallow points in a river, where it might be low and slow enough for people and animals to wade across. Often, local people would improve a ford by putting stones into it to make it even shallower.

Ferries were just little boats, frequently attached to both banks by a rope or chain tied to a tree on either side. Neither method was ideal though, so, the art of bridge building developed. At first, it was hard to make strong, long bridges that would allow a heavy cart to cross safely, so towns were situated a long way up the river from the mouth but, as techniques improved in the last thousand years or so, cities started to appear very close to the sea. In the case of Budapest, the capital of Hungary, the building of good bridges across the River Danube united the formerly separate towns of Buda on one bank and Pest on the other.

And it is this difficulty in crossing them that makes rivers good natural barriers. This is why rivers often mark the border between two countries, like the Rio Grande that marks the border between Mexico and the U.S.A. Even as recently as the Second World War, whole armies could be delayed for weeks and even months if the bridges were down and the enemy was waiting, armed and ready on the other bank.

Finally, ‘the river’ has always been a strong theme and symbol in art and literature, with Mark Twain’s ‘Huckleberry Finn’, set on the Mississippi River in the Southern U.S.A., and Joseph Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’, set on the Congo in central Africa, being just two examples. The river often represents change and the passage of time. But, more than anything, it represents ‘life’ as it travels from its source or ‘birth’ to its end and ‘burial’ in the sea only to flow again through the clouds to its place of origin.

An eternal cycle.

If you want to watch some videos on this topic, you can click on the links to YouTube videos below.

If you want to answer questions on this article to test how much you understand, you can click on the green box: Finished Reading?

Videos :

1. How Aerosols lead to Extreme Rainfall (3:58)

2. Types of Clouds- Cirrus, Cumulus, Stratus, Nimbus (5:54)

3. ‘Nile’ – Know about the World’s Longest River (1:18)

4. The Story of River Ganga (8:18)

5. Danube River (2:48)